Go

to the Archive index

Go

to the Archive index

George Wallis was born in Grimsby in 1903, but was brought up in Sheffield where his father had sold the family boilermaking business and bought a motor garage and dealership. The family moved south just before the First World War and prospered until its end, when the business went broke. George was apprenticed, aged fifteen, to the Phoenix Car company of Letchworth. They went broke. George started his own business buying, restoring and selling motor cycles. He did very well, but lived even better, and he went broke.

His father apprenticed him to a Maidstone engineering company at some considerable cost. George's abilities attracted the attentions of the Rootes Motor Company who offered him a job.

George took it without telling his father, but got bored. He smiles, remembering, and his strong, Yorkshire accent broadens out a little. "So I buggered off to London." He wrote to Perry Thomas, whose car-engineering shop at the Brooklands race track was the acme of European motor engineering of the time, and persuaded Thomas to take him on. "I just told him how good I was." Within six months he was approached by the boss of the Harley-Davidson racing team and asked to run their English operation, handling everything from administration to engine preparation. He produced three bikes from the five that were sent from the States, and on their first outing at Brooklands, they won the 200-mile solo, the sidecar and the Hutchison races. He was just 21.

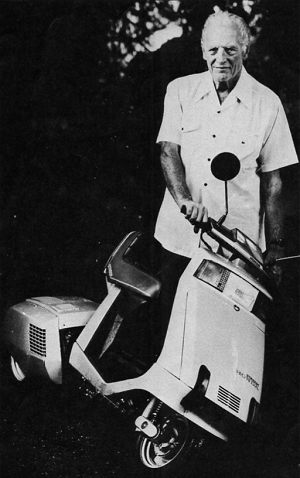

He is now 80, and, as a result of glaucoma, is temporarily only sighted in one eye. But his mind and wit are as quick as a fencer's, and his smile and humour as broad as his accent. He has exceptional recall, and tells his stories well. I suggested at one point that he must get bored recounting his life to journalists. "Oh no", he said with a dry laugh, "I've never done it before".

Harley wanted George to go to Milwaukee, but he had other plans. He had designed and built a hub-centre steering bike which had been successfully raced in 1926. An acquaintance had volunteered funds to produce and develop it, and they took a stand at the Olympia show.

Alas, they received too many orders and the backer's feet grew cold. The project collapsed, though not before The Motor Cycle had reported on it, describing George (who looked like a Hollywood leading man in his grand fur coat, fedora and William S Hart expression) riding the machine standing up whilst taking great kicks at the handlebars to prove the bike's incredible self-steering ability.

Arthur Bourne, the magazine editor, realised Wallis's potential, and recommended that he become involved with the Australian Speedway team, which was due to take on the Brits in London.

George did. He was contracted to create and run workshops for the Aussies, and to supervise their every need. Typically, he didn't just do a good job. Realising that the future of speedway racing lay with single-cylinder engines, he adapted an old Harley design and produced his own speedway machine. It won races. He built frame kits which could take a variety of engines, and sold a thousand of them. The Wallis was the bike to have. George joined up with the Crystal Palace club on a salary with royalties, selling the riders his machines, running a 'community workshop' for development and repairs. The club won every match of the season. "And that was jolly good." Then they went broke. He was employed by the supporters' club at Stamford Bridge Speedway. "We did very well. It worked out jolly fine." But the Club directors turned the track over to dog-racing.

Plymouth wanted him, so he sold up and moved west.

Plymouth went bust. "And that was dreadful. I'd worked a whole year for nothing." You might feel at this point that George was an innocent abroad, a talented but unlucky engineer, running out of options. You could not be more wrong. He had done extremely well financially, and had established a reputation as a resourceful, imaginative engineer with a flair for management. And he was still not 30. It's not for nothing that he describes himself as "a businessman first, an inventor second and an engineer third". In 1934, George was moving into his most businesslike and inventive period so far.

He had it in mind to invent a weather-protected two-wheeler, with a metal apron, running boards and small wheels. A precursor of the scooter, in fact. He was looking for a site, and approached two restauranteurs on the Kingston by-pass about their large garage premises. The two men prevailed upon George to run this garage for them, as it was a liability. He eventually agreed. "Any 'ow, long story short, I got the lot for £200 a year." He made a packet repairing crunched Humbers and the like, and still produced his speedway bikes.

Then one day a kid came in and paid cash for a speedway bike. Three weeks later he came back to buy another one. At £80 a time, the bikes were not cheap. George discovered that the kid's father ran a small coffee shop. He thought about this, did some homework and opened a small cafe himself.

In his first year, he netted £1,500 profit, the equivalent, as he puts it, of six times a bank manager's yearly salary at the time.

By 1939 he was coining it. Guessing that war was on the way, he offered his services and was asked if he'd like to manage a factory in India. He told the 'size-eight hats' brigade in Whitehall what he thought of that idea and instead spent the war with Combined Ops, manufacturing vehicle spares.

He was paid 50 shillings a week compensation for losing his cafe. "Well, that was a dead loss. Any 'ow, long story short, the war ended." He re-opened his cafe.

Behind the counter he was spotted by a senior executive from Decca, who insisted that George meet his boss. George talked his way into a contract to redesign and produce the mechanical parts of Decca's new 5 inch radar system. He also designed and produced flight logs and marine track plotters, employing some 40 or so workers. He bought a large house with 3.4 acres of garden and, on holiday, put his mind to working out how it could be more easily fertilised. He designed a 'muck spreader', and offered it to Fisons for £1,000. They turned it down. A year later he exhibited it at a horticultural show. "The show was a disaster: three schoolboys and a Frenchman turned up. I sold hundreds." Over the years the hundreds became hundreds of thousands.

Fisons asked for it, and got it.

For £120,000.

George sold his radar business to Decca and leased them his cafe.

George demonstrates the banking principle

He still had twenty or so men working for him making parts for cameras, and had dreamed up the idea of a banking three-wheeler cycle. Raleigh took up the option at first, but bad marketing blew the unpowered version. George rigged it up with a motor and BSA took an interest. George granted them a licence to produce it world wide. "And they produced an abortion. I told Jofe (Lionel Jofe, BSA's top man) and Eric Turner. Jofe agreed, but it had all gone too far. Well, any'ow they went bust. Luckily, I had a buy-back clause anyway." Daihatsu stepped in. It took two weeks for them to agree terms ("BSA had taken eight months," George growls) and despite his fears that the company had too few outlets, the Daihatsu 'Hello' sold well.

"We had a good agreement, and that was jolly good." Five years on, Honda contacted him, asking for a licence. Instead he sold them the company. For over £200,000.

My visit was George's first chance to see the Stream. He was impressed with its finish and styling. "But they've missed the whole point," he says, sadly. "My idea had torsion bars either side of the frame, so that pressure was equally distributed on both rear wheels. And the track is too narrow. This one would be unstable at higher speeds. The luggage capacity should be greater, and it feels wobbly to ride. But without the torsion bars, I can't see the point. That was the invention. That's what they paid for." He explains with a pencil and paper. He can't make reference to his original designs - he sold Honda everything. He earned more that way. In his work, George is not sentimental. He has made a fortune from inventing and developing ideas, then selling the whole shooting match time and time again. Now, with no factories in which to develop his ideas, he is a little frustrated. However, when his eyes are straight again he'll think about it. At 80, he has plenty of time on his hands. Time to take holidays, which is where he has all his best ideas. In fact he recently returned from a round-the-world trip.

"I 'ad lots of ideas" he smiles, "but now's not the time for them. In business, timing is crucial. There is one though that I'm considering: a combustion engine powered by coal dust. After the operation I'll think about it". He took the Stream for another ride and came back, smiling. "It's the first time I've ridden a bike since the Ariel 3" he said "and the time before that was on the hub-centre job at the TT". "Did you race at the TT?" I asked, surprised, as I prepared to leave. "Don't be daft," he said, waving goodbye, "I'm far too intelligent for that".

First published in Which Bike?, October 1982