at the Sign of the Hygra

2 Middleton Road

London E8 4BL

Tel: 00 44 (0)20 7254 7074

email: boxes@hygra.com

Antique

Boxes in English Society

1760 -1900

by ANTIGONE

Tea Caddies and Tea

|

ANTIQUE BOXES at the Sign of the Hygra 2 Middleton Road London E8 4BL Tel: 00 44 (0)20 7254 7074 email: boxes@hygra.com |

Antique

Boxes in English Society |

| Tea Caddies and Tea | Home |

Contents |

Back |

Next |

Thumbs |

Tea was introduced to England from China sometime in the middle of the 17th century. Although there are earlier references of its use by traders in China, it was not until 1657 that we have the first account of its sale in England. Together with the fragrant leaf came the respect for this drink and the ceremonial way in which it was to be prepared and drunk. Tea was pivotal in the history of Britain in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. To understand the full impact of the importation of tea we have to consider the fiscal implications of this newly introduced commodity. We also have to realise that the tea and opium trade were inextricably interlinked.

|

At the time of its introduction, tea was

believed to be therapeutic as well as delicious. The

health benefits of tea were known in the East for

thousands of years. In England people accorded it time

and space and this alone must have had the effect

of producing a sense of well being. At first the

drink was enjoyed in the established coffee houses

frequented by the intellectuals and the men of the world.

It was prepared in advance in large containers for the

excise man to levy his duty before it was sold. |

In 1662 when Charles II married the Portuguese Catherine of Braganza she introduced tea to the court. Holland and Portugal were fifty years ahead of England in importing tea. Tea was and remained extremely expensive for over a hundred years and therefore sparingly used.

In Henry Fielding's "Joseph Andrews" (1742) the

eponymous Joseph is carried badly injured to an Inn where he asks

the landlady for"a little tea". The landlady would not

hear of it and offers instead "a little beer". At first

tea was only sold through apothecaries, coffee houses,snuff shops

and through shops catering for ladies needs . However by the

second half of the 18th century smuggled tea was so widely

available, that it was a matter of course even for respectable

people to buy it illegally for less money.

William Pitt tried to address this problem in his Commutation Act

of 1784, which reduced taxes on tea and halved its price. The

legitimate imports quadrupled making tea more accessible to a

wider section of society. More teahouses and tea gardens opened

and more homes prepared it as an after dinner delight. However

the ups and downs of tea are much more complex and can only be

glimpsed at by understanding the underpinning policy of trade

colonisation which links it with opium.

THE FIRST TEA CADDIES

Although wooden Tea Caddies were made early in the 18th century, it is not until the second half of the century that they were introduced in any numbers as a home style accessory.

The word caddy derives from the Malay "kati" a measure of weight about 3/5 of a kilo. The 17th century tea containers were bottle shaped tea jars in china, glass, silver, enamel and straw-work covered metal. I do not intend to discuss these here. What I will deal with are the box shaped wooden caddies and the wooden caddies veneered in tortoiseshell, ivory, horn, straw-work and sadeli mosaic.

Tea Caddies were made in wood in box form from the second

quarter of the 18th century. The first such boxes were shaped

like small chests and contained three metal canisters. They were

mostly made of mahogany although a few early ones were of walnut.

Very occasionally a chinoiserie box was made. Complete boxes of

this type are difficult to find, especially in walnut.

Chinoiserie boxes are exceedingly rare.

|

A good example of a mahogany caddy still with its metal containers c1775 |  |

The style of these caddies roughly falls into two categories:

the austere and the rococo, which was fashionable for a brief

period in the 1760s. Both styles share certain characteristics.

They both have handles on the top and mounted escutcheons. Where

they differ is that the rococo boxes have more elaborate, mostly

gilded brass mounts, which also form the feet. The others stand

on bracket feet, or on a plinth support base. The lids on both

are stepped, the step often concave. The edges are frequently

moulded. The sides are mostly straight although sometimes they

are bombe shaped. Very rarely is there any decoration. The odd

rare example is known to have tracery carving in the manner of

Chippendale, banding the box just above the base.

|

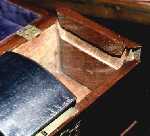

Details showing secret compartment which is revealed when one of the sides is slid upwards. |  |

A few of these caddies have a secret space just above the base, which is revealed by sliding one of the sides of the box. The inside of the lid is lined with velvet and occasionally there is a space for caddy spoons on the lid or the back of the caddy. Chest type boxes were also used for housing silver caddies. These were covered in shagreen, tortoiseshell or ivory. Metal mounts (escutcheons, handles, feet, and other decoration) were of silver or gilded brass.

Although still seriously expensive, more households were drinking tea and wanted caddies to keep their precious leaves fresh and safe. The cabinetmakers saw the opportunity of introducing new designs, woods and shapes to their clientele. It also made sense to introduce boxes, which could be completed in the same workshop. This gave rise to the all wooden caddy with a wooden interior.

By the 1770s the mood of fashion was changing. Earlier in the century excavations at Herculaneum and Pompeii revealed a different grammar of aesthetics both in ornament and shape. Drawings and prints of these finds were circulating among architects and designers and began to be translated in pattern books of furniture and architecture.

Designers, architects and well to do men trying to improve their knowledge travelled to Italy, Greece and North africa taking with them their writing boxes.

Robert Adam the important neo classical architect, whose name is often used to describe the new eclectic style, worked in London from 1759 to about 1768, after studying and making detailed drawings of Italian buildings. He emphasised unity of architecture and design and this ethos dominated the thinking of the end of the 18th century.

The cabinetmakers of the 18th and early 19th centuries were highly sophisticated and had perfect control of the art science and craft of their profession.

To illustrate the change of style in the last decades of the

18th century, we can compare Thomas Chippendale's designs for

"tea chests" in his 'Gentleman and Cabinet Maker's

Director 1762' and

|

A drawing of an oval tea caddy from George Hepplewhite's The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Guide. Click on the drawing to see all six of Hepplewhite's designs of tea chests and tea caddies. |

George Hepplewhite's designs in his 'Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer's Guide' of 1788 in which he offers both chests for metal containers and all wooden caddies. Comparing the chests in the two design books we notice similar use of straight, concave and convex shapes, but in the Hepplewhite boxes the rococo ormolu mounts are replaced with neo classical style inlays. The look is more restrained.

The decoration on the three Hepplewhite caddies is also in the neo classical Adam style and mirrors many of the motifs, which were currently in use. Paterae, stylised flowers, festoons of flora, urns.

The caddies are the three prevailing shapes of the late 18th century. Square, oval and oblong. They are flat on the top and they have no feet or other support. Two have small drop handles on the top.

The late 18th century caddies are single,

double or triple.

That is they have one, two or three separate compartments.

The late 18th century caddies were made of pine, oak or

mahogany and veneered in different woods. This enabled the makers

to make the best use of rich figuring in the wood as many

surfaces could be cut from the most beautiful pieces. Native

fruitwoods as well as more exotic woods, which were imported,

gave the cabinet makers more scope for designs.

Cutting veneers by hand was a highly skilled job. The veneers

were much thicker than what we think of now as veneers. This

created structural problems, such as the edge of the veneer (end

grain of the wood) which could allow moisture to be absorbed if

it was not sealed. An elegant decorative solution dealt with this

problem. The caddies were edged in strips of contrasting plain

wood, usually holly or boxwood or in herringbone designs.

Often well figured wood was only enhanced with an edging and a

small handle in the centre. Stringing and cross banding were also

effective elegant decorative devices. We find simply decorated

caddies in well figured veneers such as partridge wood,

satinwood, burr yew, hare wood flame or fiddle back mahogany and

others. The variations are endless.

Extremely rare is the use of carving in strong

classical designs.

|

A carved three compartment tea caddy of the end of the 18th Century. A cellerette of similar style made in 1775 by Thomas Chippendale for the Lascelles family can be seen at Harewood House in Leeds. |  |

More complicated decoration was used almost always on boxes made of plainer mahogany or other woods.

Marquetry was by far the most prevalent form and this was done in two ways.

Caddies were priced according to the wood, shape and

decoration.

PICTURE OF CADDY |

The picture on the left shows a good

example of a conch shell inlay within an pre-prepared

panel. The picture on the right shows an example of inlay directly into the top of the caddy. |

ENLARGE |

Wooden caddies of this period were usually finished in wax and turpentine and good examples have built up a mellow rich patina. Running one's hand across the wood one notices minute unevenness on the edges of inlays and edgings. Restoration must be done with the utmost care. Refinishing with glossy later hard polishes destroys the particular beauty of this early wooden surface.

In addition to these caddies which were constructed by

cabinetmakers there is another type dating from this period and

which continued to be made well into the 19th century. These are

single wooden caddies made by turners in the shape of different

fruits, mostly but not exclusively, apples and pears. These were

turned rather crudely and it makes me wonder how many were made

by grandfather when the family apple tree was felled. Early

examples have iron or silver hardware. Some which have survived

with a good patina or traces of old colour have a certain rural

charm, but I suspect it took the 20th century collector to raise

their prices to such heights.

Satinwood and other light coloured woods were used to veneer caddies destined to be painted. Most of these are in the manner of Angelica Kauffmann with floral swags and putti. Small caddies were sometimes covered in paper and then painted and gilded. These on account of the fragility of the material are now very rare. Another very rare type of painted caddy is in the form of an 18th century house.

18th century papier mâchè caddies are exceptionally rare. They are made of the old Clay type of material and they are small single containers. They are discreetly decorated in the neo classical style with paint and gilding. Their hinges and escutcheons are very fine.

|

The first straw work caddies known in England were tin 'Jars' covered in straw work and brought most probably from Holland, in the 17th century. There is an example at the beginning of this article. However by the late 18th century straw work covered wooden boxes were made in England in very small numbers. The designs follow the neo classical style. Such boxes are now so rare that very few collectors have even seen one. However fortunately the intricacy of the work makes restoration impossible and thus surviving examples have escaped the abuse of "re finishing".B |

| A late 18th Century

English strawwork caddy. |

Very few caddies were decorated in chinoiserie. Green and dull red examples are particularly rare.

Some very fine caddies were made at the end of the 18th

century. The controlled use of precious materials in simple

shapes enhanced its natural beauty. (TORTOISESHELL

AND IVORY)

|

On the left is an example of a late

18th Century ivory tea caddy. On the right is an example of a late 18th Century green tortoiseshell tea caddy |

|

All English caddies of this period were lined with a tin lead alloy "tea pewter" except the ones, which contained removable metal containers.

Anglo-Indian ivory and Chinese export lacquer caddies were brought from the end of the 18th century. However serious importation did not start until the beginning of the 19th century (SEE ANGLO-INDIAN and CHINESE EXPORT LACQUER).

The Chinese caddies had removable soft metal containers, which were engraved with floral or oriental designs. Unlike most of the other caddies of the period they were large in slightly rectangular shapes. The sides were straight and the tops flat.

EARLY 19th CENTURY TEA CADDIES

This period is often referred to as the Regency period. Although this is not historically strictly correct, the Regency dates are 1811-20, there is some justification in the description. George the fourth came of age in 1783 became Regent in 1811, King in 1820 and died in 1830. The whole of the early nineteenth century period has a distinctive stylistic flavour often indulged in, encouraged and promoted by the prince later to become the king.

By the last decades of the 18th century the philosophical, stylistic and financial certainties of the mid eighteenth century were already undermined by exposure to different cultures. Improved transport and trade changed both cultural perceptions and social structures. The neo classical designs of the last two decades of the century were only the beginning of a natural progression to even stronger departures from the old English forms.

The neo classical influence of the 18th century, which in the case of tea caddies translated itself in straight shapes and stylised ornaments, developed in the early 19th century to the adaptation of classical architectural forms and shapes in the construction of boxes.

Parallel to this the Chinese influence was also felt, as was the inspiration derived from the heavier Egyptian classicism.

Tentatively at first tea caddy makers began to experiment with these new shapes. Some caddies made in the first decade of the century have 'pagoda' tops, or tapered sides.

Before long the shapes became more robust. The sarcophagus shaped box predominated in its many variations. It could be simply tapered with a stepped top,or it could be bombe, concave, convex or even made in a mixture of different linear combinations. It could have a domed lid, three-dimensional panelling, gadrooning or any combination of architectural elements which were in vogue.

The shape of the caddies was often enhanced by standing them on turned wooden feet or on feet made of brass, sometimes gilded. The metal feet were also inspired from the ancient world and took the form of animal paws, or bird talons. Sometimes they were in the form of clustered formal flowers. Side handles in a complimentary design to the feet were often added, such as lion masks, two headed eagles or baskets of flowers. When the feet were made of turned wood so were the handles.

As the shapes became more complex, the inlaid wood decoration

became less popular. Early sarcophagus shaped caddies in mahogany

veneers depend on the form of the box and the richness of the

figure for their aesthetic appeal. Some are built with panels

sunk in a frame, edged with gadrooning. The whole structure is

managed on architectural principles and the final result is

strong and impressive.

Rosewood and kingwood complimented the metal feet and handles well and apart from narrow boxwood edgings or gadrooning the boxes often have no further decoration.

Thomas Sheraton's Cabinet Dictionary 1803 and later publications suggests many of the features for furniture ornaments, which were also adopted for tea caddies: animal monopodia, curved shapes, brass ornaments, brass inlay lines,contrasting wood marquetry.

Caddies in well figured mahogany, rosewood or kingwood began

to have discreet brass decoration made up of brass stringing and

roundels. Brass escutcheons in more complex shapes replaced the

earlier diamond shaped bone/ivory ones.

Mother of pearl as a material for inlay was not used on tea caddies until the second or third decade of the 19th century. It was possibly its use in papier mâchè boxes that alerted the woodworkers to its potential as accomplishment to dark and glossy woods. This combination produced some fine and striking boxes.

The caddies decorated in this material fall into two categories. Simple rectangular or sarcophagus shaped decorated in pewter stringing with mother of pearl circles in the corners and mother of pearl escutcheons or just mother of pearl escutcheons and gadrooning.

The second category is caddies in sarcophagus shapes with fine designs of birds animals and flowers. These sometimes have the escutcheons incorporated within the design. They invariably stand on turned feet and sometimes have flat or loop and ring wooden handles. The inlays were the work of skilled designer craftsmen and are such they are mostly very fine.

Tunbridge Ware

|

A very important group of tea caddies produced in the

first three decades of the 19th century are of course the

Tunbridge Ware boxes.

Shapes are similar to other caddies of the period with

the exception that the nature of the decoration precludes

extreme bombe or concave shapes. In the first thirty

years of the 19th century, caddies were usually made in

rosewood veneer with Van Dyke (elongated triangles) and

cube pattern parquetry decoration. The earliest ones, like the one illustrated here, do not include mosaic inlays, although these do appear in the 1830s mostly as borders. In the 1830s and 40s the early patterns were combined with mosaic marquetry in Berlin woolwork designs. Turned feet were usual, but not handles, which would interfere with the decoration which, continued on all sides. There is an example of a later Tunbridge Ware caddy later in this article. |

Penwork

Penwork and painted caddies from this period reflect very strongly the often conflicting influences of the period, which gave it its particular vibrancy and charm. Shapes are the typical shapes of the day. Feet and handles are usually of gilded brass. Decorated both inside and out with oriental, classical, English romantic, or naturalistic themes, they are a joyous celebration of the access of the nineteenth century to such diverse cultures. PEN WORK)

Papier Mâchè

Papier Mâchè tea caddies in the early decades, mostly

the 1820s 30s and 40s were mostly double. The earlier ones were

painted and gilded. After 1825 mother of pearl decoration was

introduced and used in conjunction with painting and gilding. The

double caddies were of curvilinear, sarcophagus or oblong forms.

They had two lids inside. Slightly later going on to the middle

of the century a few caddies of triple form were produced. These

had canisters inside and the glass bowl arrangement in the

centre. They were splendidly decorated and their impressive

shapes were usually rounded. (SEE PAPIER

MÂCHÈ)

|

Tortoiseshell caddies of the early 19th century are double, sometimes in subtle architectural shapes with gently rounded tops, ivory or silver plated feet and finials. Inlays in silver and mother of pearl are from the second decade. By the 1840s shapes become fussier, such as serpentine or combinations of curves and flat surfaces. Feet are in turned ivory which is sometimes stained. Usually these have no finials. |

| Tea caddy in tortoiseshell veneer,

edged in carved tortoiseshell and faced with ivory. Carved decoration was used on only a very few caddies. English c1800 |

|

| Anglo Indian caddies of this period are very rare. In caddies made of horn, the sarcophagus theme has the dimension of texture and depth given by lids constructed in reeded and radiating pieces of horn. Sadeli mosaic in simple shapes and exquisite patterns. |

| Chinese Export Lacquer | ||

|

Chinese Export Lacquer tea caddies dating from the early part of the 19th century are shaped. Their shapes are an attempt at the sarcophagus form interpreted into a rounder and more organically grown whole dictated by the material and the method of construction. There are variations of the shape but basically it is a rounded version of a foreshortened rectangular form with gently stepped lid. Single round examples as well as more unusual shapes like melons, gourds and butterflies also exist. These caddies contain pewter removable canisters. There are also large square caddies from this period. The shaped caddies often have wooden gilded feet. These echo the fashionable European lion feet. Superior carved feet with dragon heads or Chinese dog heads are also found. | |

MID to LATE 19th CENTURY TEA CADDIES

The first half of the 19th century saw great social and

economic changes. Medical improvements contributed to the

increase of the population of the country to 18 million, double

of what it was fifty years previously. Trading with other

countries gave opportunities to more people to increase their

wealth and their social standing. Country towns almost unknown a

hundred years previously developed their own class structures.

The potential for tea drinking was reaching new heights. The

government being aware of the pressure to reduce prices took a

major step in 1833 by withdrawing the monopoly of the East India

Company to import tea. This reduced prices considerably. In 1839

another major development happened in the history of tea. Up to

that date tea was only imported from China. In 1839 tea began to

be imported from India too. The India trade was encouraged and

developed and tea became much more accessible. Tea caddies

to house everybody's tea were by now in even greater demand. New

mechanical processes made it easier to cut thinner veneers.

Brunell patented such a machine in 1805 although it was not until

the late 1820s that they were generally used. Even then, superior

timbers were cut in thicker slices for the production of quality

pieces. By the 1840s New Zealand was added to the list of

countries exporting timbers to England and together with the

timbers from the Far East and Africa and the Americas there was a

wealth of choice. What is interesting at this time is the

dichotomy of quality between the caddies made for the average

citizens and the caddies made for those who aspired to a superior

style and could pay for it.

|

In the second half of the century a great number of

caddies were made of pinewood veneered with walnut and

decorated with strips of geometric inlay in different

woods. The quality of this marquetry varies a great deal,

although the positioning of the inlay, either as two

perpendicular strips or a surround makes for a sameness

of effect. These caddies are double with two lids on the inside. They occasionally have a domed top and they are of a modest size. Occasionally a more special one was made in a more curved shape. |

These caddies were made without any pretensions and they were retailed from several outlets. They are still relatively easy to find and make pretty additions to the home.

Other caddies made inexpensively were caddies in the earlier

simple shapes using thinner veneers.

The styles prevalent in the more expensive caddies are not as

innovative as those of the early part of the century; rather they

are elaborations on similar lines.

After the Napoleonic wars the prevailing patriotic sentiment was translated in architecture in the Neo Gothic revival. This influenced the production of furniture and home accessories in the 1830s and 40s. In terms of caddies it was translated in boxes made in dark rich coromandel wood, or occasionally in walnut. These caddies were mostly double with a rounded or pointed top. They had brass strap decoration (gilded in the best examples) with either engraved or cut out Gothic inspired motifs.

1848 saw the first influx of French craftsmen who fled France

because of political troubles. They probably suggested some of

the decorative techniques developed at this time.

|

French caddies in ebonised wood and rosewood with THE inlaid in brass or white metal were made in the earlier part of the 19th century. These were translated into inexpensive English caddies in combinations of rosewood and light wood, with TEA inlaid on the top. |

A more successful style import was the combination of brass

and mother of pearl inlay. This was already done in France. The

English versions of this work are not copies of French work, but

a use of the technique for the creation of more free flowing and

strong designs. Tea caddies were made of coromandel or dark

rosewood and the front and top inlaid with stylised flowers on

stems. The stems were made of brass wire and the flowers of

mother of pearl and brass. The shape of the box was simple

sarcophagus with turned feet. The veneers used for these,

although mechanically cut were much thicker than the veneers cut

for the inexpensive boxes.

|

Papier mâchè caddies of the early part this period tend to have elaborate mother of pearl decoration and in the best examples fine gilding. In the later years of the century the quality of the decoration declined together with the rest of the papier mâchè industry. |

Tunbridge Ware caddies flourished in the middle of the century

until the 1870s. They came in all the shapes already mentioned

but with very elaborate decoration in mosaic marquetry.

|

There are caddies with castles, flowers, birds, butterflies, persons, decorated both inside and outside. Sometimes earlier cube designs are also incorporated in the many happy and not so happy combinations. |

The notable Tunbridge Ware maker, Russell, made his own contribution to the neo Gothic revival by producing caddies with marquetry inlay reminiscent of ecclesiastical windows.

Impressive large caddies veneered in burr walnut, coromandel, burr and pollarded woods were occasionally made in the second half of the century, but as tea drinking lost its social appeal, the demand declined.

|

Chinese export lacquer from this period also seems to come in two qualities. The shapes are similar to the earlier caddies but the inexpensive examples are in simpler shapes and decoration. |

Anglo Indian caddies of the middle 19th century and later are

carved with strips of later period sadeli mosaic.

Pre packed tea was first sold in 1826 but it was not popular

until the 1880s by which time it was sold in grocery stores. The

era of the craftsman made tea caddy was coming to an end.

© 1999 Antigone Clarke and Joseph O'Kelly