glimpses of my life and thoughts

national service (1) 1944-1946

Life as a Bevin Boy

Indian Independence

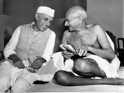

On 15 August 1947 India celebrated independence from British rule.

The picture left shows Mahatma Gandhi, a key architect in the process, with India’s first prime minister Pandit Nehru. Within 5 months Gandhi was assassinated.

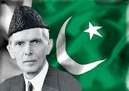

On the same day Muhammad Ali Jinnah (right) became the first governor-general of the newly created independent Muslim state named Pakistan. He died a year later.

Anticipating violence in Bombay, a strict edict was issued to all personnel to remain in the camp during Independence Day and until further notice.

So three of us whose natural disposition was non-conformist got into our civvies and took a taxi into the city. The crowds that we met were at least as large as those recently seen in Cairo, shouting, waiving flags, gesticulating not in protest but in jubilation.

As representatives of the nation that had taken so long to relinquish power we feared what might happen to us. We were surprised to be hoisted onto shoulders and carried high along the main street, people shaking our hands and saying thank you oh yes, thank you for giving us our freedom.

We smiled and waved royally.

The RAF Mutiny

The war in Japan ended in August 1945. With tens of thousands of British troops stationed in the Far East there was a logistic problem of getting them back home. Most had been there for three years or more, many of them battle-scarred and still suffering appalling deprivation.

In January 1946 nearly 1000 RAF personnel based near Karachi went on strike mainly in protest at the delay in demobilisation, causing a domino reaction that allegedly spread to over 50,000 men in 60 RAF stations throughout Asia, the biggest act of defiance in British military history, so it is said. Indian personnel in the RAF were also involved, their grievance being over the conditions of service.

A Court Martial that ensued seems to have fizzled out due to legal wrangling.

By the summer of 1947 it was claimed that an extra 100,000 men had been released from service and returned to the UK. Most of these were channeled through BRD Worli near Bombay, the RAF station designated to deal with the repatriation of troops.

It was at BRD Worli that I spent the best part of two years from the Autumn of 1946.

Physical hazards

As we were dependent on hand-held Davy lamps for light there was always the lurking danger of an explosion. It was reassuring when the safety officer came on his rounds to test the methane level.

Another constant anxiety was the danger of falling rock. Once Trevor called to me to come over to him on the other side of the dram. When I delayed he shouted, ‘Come here, Dai Bach, NOW”. So I did. Tons of rock then fell from the ceiling onto the spot where I’d stood seconds before. A miner’s sixth sense they call it.

Sometimes deaths were caused by foolhardiness, such as when I stumbled in pitch dark (my lamp had gone out) upon the body of a man who had tried to ‘hitch a lift‘ between two drams as they were being hauled by a pony to the pit bottom. He’d slipped and broken his neck.

My scariest moment was when at the start of the shift we were going down the shaft in the cage at 30 mph when the lift stuck and the cable above started to unwind on the top. We managed to dislodge the cage by rocking it. It then dropped a few feet under gravity before the cable took up the slack, mercifully without breaking.

The outcome could have been very different.

An Airman’s lot

At the beginning I found the atmosphere soulless and depressing. One reason for this was that I missed the comradeship of the mining community I’d left a few weeks before. RAF life was by comparison impersonal. You were just a number not a person.

I was a poor recruit. One early morning during initial training I spent a good 20 minutes polishing my boots to a mirror finish. On the way to parade a few specs of sand had sprinkled onto them, quickly to be spotted by the loudmouthed corporal as he inspected his men. “What sort of fucking polish do you call that, Aircraftman?”, he bellowed. “Excuse me, Corporal, but ..“, I began.“ “EXCUSE ME?”, he roared. “I’ll bloody well give you EXCUSE ME. You’re on a charge for insubordination.” I almost wept. Fortunately I didn’t. However I got my own back: my punishment was to spend time in the office, so I simply filled out a pass form giving myself a weekend leave that I wasn’t entitled to.

Life got much better when I had the good fortune to be sent to India, a country which made a huge and lasting impression.

In the summer of 1946 I developed chronic miner’s elbow resulting in my discharge from the mines. Within weeks I was passed A1 for the armed forces and shortly afterwards joined the RAF.

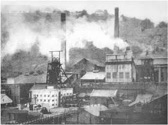

Working in a South Wales mine

If going from school to college was a culture shock, moving from the esoteric environment of a Cambridge college to this was like landing on another planet.

After a brief but intensive training at Oakdale Colliery in South Wales I worked at Llanbradach pit in the Rhymney valley and lived in a corrugated Nissen hut with other Bevin Boys in the village of Ystrad Mynach a 20 minute train journey away.

Llanbradach Colliery

On hands and knees or lying on his side Trevor worked at the coal seam with a pick. My job was to heave massive lumps of the coal by hand into a dram (truck). He was paid by the ton of coal produced (piecework) in his seam. I received just over £2.50 a week whatever the output. He got paid for looking after me, too!

We breathed in coal dust constantly, filling fingernails mouths, nostrils and lungs — small wonder that so many miners came to an early end from pneumoconiosis.

My early attempts to do this job were greeted with derision by a group of miners who had gathered to watch. I looked up to see their faces wreathed in silent mirth. So I got better at it. Once they started to call me Dai Bach I knew I was OK.

When on dayshift in the winter we arrived at the pit in the dark and it was dark when we emerged in the late afternoon. It was a joy to see the light on a Sunday.

The political background

I was well out of my depth politically. The miners were mostly highly articulate and knowledgeable about party policies and political history — left wing, of course, and strongly antagonistic to the Prime Minister Winston Churchill who as Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1926 had brought in the army to quell the miners’ strike.

Working with the mining community and to some degree socialising with them made a lasting impression that has influenced my thinking ever since.

A coal seam

Llanbradach colliery

national service (2) 1946-1948