Somebody

produces a foot- ball, and these ghosts form up in teams (for there must always

be competition, if not conflict) and they playa riotous and chaotic game.

Somebody wins, the uniformed throng exchanges trophies, and the vision fades.

Somebody

produces a foot- ball, and these ghosts form up in teams (for there must always

be competition, if not conflict) and they playa riotous and chaotic game.

Somebody wins, the uniformed throng exchanges trophies, and the vision fades. Source: THE DAILY TELEGRAPH Sunday, December 23, 2001.

WHEN

FOOTBALL STOPPED PLAY.

Review by Russell Davied.

Silent Night: The

Remarkable Christmas Truce of 1914 by Stanley Weintraub. Simon & Schuster (£12.99)

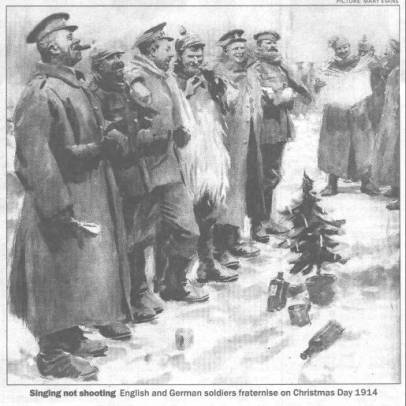

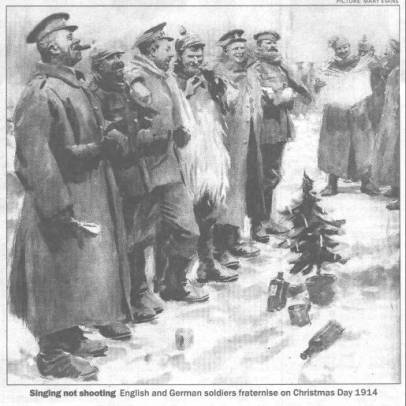

The witnesses to the First

World War, its participants and survivors, are almost gone. But vaguely, down

the years, persists the vision of mud-caked men scrambling out of trenches at

Christmas 1914 and stumbling into no man's land with disbelieving expressions on

their faces, to greet the unarmed enemy equally baffled by a sudden truce.

Somebody

produces a foot- ball, and these ghosts form up in teams (for there must always

be competition, if not conflict) and they playa riotous and chaotic game.

Somebody wins, the uniformed throng exchanges trophies, and the vision fades.

Somebody

produces a foot- ball, and these ghosts form up in teams (for there must always

be competition, if not conflict) and they playa riotous and chaotic game.

Somebody wins, the uniformed throng exchanges trophies, and the vision fades.

It has taken nearly 90 years to

bring this event back into focus again. Professor Weintraub, whose list of

sources is as long as the chapters in most people's books, has raided every

memoir, newspaper, regimental history and hoard of correspondence he can find in

order to present a picture of life - and for about 48 hours, it did at least

resemble life- along the front line during that curious Christmas time.

The truce happened; and although there were precious few footballs available (why should there be?), that outbreak of comradeship was both more comprehensive and more fragile than legend relates.

The movement came from below, and

largely, it seems, from the German side, which at that moment was winning the

war. By the time senior commanding officers were aware if its upsurge, it was

too big to stop. One impulse behind it was ancient and traditional: the wish to

bury the dead, who lay littered across the disputed land. Had the corpses not

been removed or interred, along with their stench and visible mutilations, the

later festivities could not have occurred. Arrangements were easily made, as the

opposing trenches lay within easy shouting distance of each other -easy singing

distance, too, as it proved.

It was the Germans, with their

better-developed Christmas traditions, who sang carols, often well enough to

provoke applause from the listening British: Stifle Nacht was never less

than moving. Often the best our side could offer by way of reply was a selection

of the rough and piercingly satirical soldier- songs they might have sung anyway

(this is not a book that flatters the British). The sometimes forgotten Indian

regiments in the lines could not join in, and were puzzled, though not

displeased, by the sudden outbreak of illuminated Christmas trees along the Ger-

man trenches -a reminder of the Diwali festival, and home.

There were some breaches of the

reciprocal trust on which the truce was based. Uncontrollable snipers,

fanatically gung-ho officers, drunkenness and sheer misunderstanding all played

a part, though frequently, when shots were fired, it was later explained by one

set of riflemen or the other that they had thwarted the belligerence of the

given orders by aiming into the air.

Soon, brave individuals took the

decision to be the first to clamber out and meet in the middle. From that

moment, fraternisation - a horror to the generals - was in progress. It was a

frosty Christmas, and the mud churned up by the first months of war had frozen

into a crust. Gifts of provisions were exchanged, toasts were The book is full

of individual feats and eccentricities. On Christmas Eve, the Royal Flying Corps

passed over the German airfield at Lille, and dropped a well-padded plum

pudding. Lieutenant John Reith, future founder of the BBC, commandeered a

chateau and laid on a candle-lit champagne dinner in its cellar.

In one bizarre incident,

competition met conflict when a German soldier challenged anyone of his enemies

"except an Irishman" to a single-handed bayonet fight. A Gordon

Highlander lurched into no man's land and, after a tough contest, killed him.

But such frightfulness was rare.

The truce straggled over into Boxing Day, and some units wanted to prolong it.

One Saxon regiment (who hated the Prussians more than they hated the enemy)

almost went on strike. But the ire of the generals prevailed, and no informal

truce of such wide application was ever mounted again. The killing resumed and,

as Weintraub remarks, "On both sides in 1915, there would be more dead on

any single day than yards gained in the entire year."

It is typical of Weintraub's

quirky thoroughness that he mentions the episode of the television comedy Blackadder

which referred to these events. And he points out that the Commonwealth War

Graves Commission lists six men called Blackadder among its dead.

Russell Davies is

a writer and broadcaster.

Source: THE DAILY TELEGRAPH Sunday, July 22, 2001.

Geoffrey Wheatcroft on

a dispassionate study of the soldiers who faced the firing squad during the

Great War.

Blindfold and Alone: British Military

Executions in the Great War. By Cathryn Corns and John Hughes-Wilson. Cassel £25.00,

543 pages.

BETWEEN AUGUST 1914 and November 1918, more than 10 million men were killed on the battlefields of Europe. A million of the dead came from the armies of the British Empire, three quarters of those from the British Isles. The Great War conditioned our lives. It became an obsession, remembrance of the glorious dead a national cult.

In recent decades there has grown up another

obsession, with one very small group of dead. The number usually given of those

British soldiers who died not in battle but in front of firing squads is 306.

Cathryn Corns and John Hughes-Wilson count 346 executed before November 1920.

Some were shot for murder, including several Chinese serving in labour corps,

but most for military offences: mutiny, cowardice, striking an officer, sleeping

on duty (in two particularly grim cases). The great majority, 266 men, were shot

for desertion.

This is at least the fourth book on the subject to

appear since William Moore's unattractively named The Thin Yellow Line in

1974, and is more notable for fair- mindedness than for profound scholarship.

The authors review both military law and the social climate of 1914, and then

numerous individual cases, from Private Thomas Highgate who was, on September

8,1914, the first soldier of the war to be executed (''as publicly as

convenient"), to the last two, shot four days before the armistice even

though in one case commutation of sentence had been recommended.

No one can read about these executions without a sense

of horror. War is hell, and none was more hellish than on the Western Front. Any

account of the first day on the Somme, when 20,000 British soldiers died on one

day and whole battalions were destroyed, may make one wonder not why so many men

broke but why any did not. Compassion and pity must be felt for the condemned

men, even the obvious scoundrels, let alone the baffled and terrified boys of 18

who didn't understand what was happening to them.

But it is not the job of historians to pass

retrospective judgment, and the authors are scrupulous in trying to understand

the period in its own terms. Of course, courts martial did their business

hastily, and their standards of forensic meticulousness were not those of the

High Court.

Cases of desertion ranged from calculated attempts to

escape France in disguise to disoriented young men wandering the wrong way in

the fog of battle. All the same, the authors have not been able to find a single

grave miscarriage of justice, where a man was obviously falsely condemned.

If senior officers in that war acquired a reputation

for pigheadedness and hard-heartedness, it was not without reason. Their

attitude to deserters was characteristic. One private deserved the "extreme

penalty", Brigadier-General Harold Fergus wrote, since "he has no

intention of fighting" and "is quite worthless, as a soldier or in any

other capacity, and is better removed from this world".

Some hackneyed views of the "donkeys"

are nevertheless wrong. Blind vindictiveness? General Haig commuted nine out of

10 death sentences. Class justice? In the well-known case of Sub- Lieutenant

Edwin Dyett, General Gough recommended that the sentence should be carried out

precisely because "if a private had behaved as he did in such circum-

stances, it is highly probable that he would have been shot".

Incidentally, Gough's minute is quoted in the text,

and on the page opposite its original appears in facsimile with distinctly

different words, which does not inspire confidence in other sources cited. That

apart, the book is too long, and sometimes repetitious.

During the Second World War, albeit to the displeasure

of some generals, and with infantry morale sometimes very "sticky",

the British Army got by without a single military execution. That was in some

degree a legacy of earlier unhappy memories.

In the most trenchant part of their book, Corns and Hughes- Wilson discuss today's Pardons Campaign which has called, so far unsuccessfully, for a complete pardon for all those executed. The authors find it genuinely difficult to understand the aims and motives of the campaign, except in terms of "shroud waving" and a culture of victimhood. Nor are they impressed by the rather kitsch "shrine to the unlucky" recently opened in Staffordshire. The campaign's "claim to a monopoly of compassion is", they say, "deeply unfair both to the soldiers who did their duty and to the commanders of the Great War".

Although there should by now be a moratorium on quoting L. P Hartley's words with which this book opens, they do apply here, if ever: the past is a foreign country.

Source: THE DAILY MAIL Saturday, July 21, 2001.

The truth about the young men who died at dawn.

An emotive campaign has been waged to exonerate the soldiers executed for cowardice in the Great War. Now a new study of all 346 deaths reveals that although harsh, justice WAS done.

The image is one of the most poignant and

disturbing of World War I: a forlorn, bareheaded, blindfolded figure pinioned to

a post while a wintry dawn breaks over the battlefield. A scrap of white cloth

pinned to his tunic flutters over his heart. A firing squad or his own comrades takes faltering aim.

Close by, hundreds of men are being randomly

massacred in the trenches. But it is this ritual death behind the lines of a

scared and lonely young man that diverts our compassion and rouses our

indignation.

It is easy enough to understand why. Over the

generations since that awesome conflict, the notion of some poor, bewildered

youth being executed for showing a moment of human fear amid the inhuman horror

all around him has come to symbolise everything the modem world finds most

tragic about the Great War.

Inevitably, he has also come to be depicted as the

victim of a heartless society in which the working classes did the fighting and

the dying, while the officer classes sent them over the top and ruthlessly

punished those whose nerve gave way.

Hence the clamour from those campaigning for a

posthumous pardon for the executed men, the wreath in their memory placed at the

Cenotaph on Remembrance Day and the moving statue of a boy-soldier awaiting

execution erected at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire.

Yet the truth is that a mythology has grown up about

the supposed injustice done to these young men which has more to do with modem

sentimentality than contemporary reality.

Viewing past actions through the prism of present

values can have a distorting effect, and few aspects of the 1914-18 war have

been distorted more than this one, according to a persuasive new book, Blindfold

And Alone: British Military Executions In The Great War.

The authors, Cathryn Corns and John Hughes-Wilson,

have done an immensely thorough job researching the cases. What emerges is far

from a slaughter of the innocents, nonchalantly sentenced to death by

moustachioed ex-public schoolboys.

WHAT is clear is that these capital courts-martial

were not some form of oppressive class warfare, or some deadly form of social

control by brutal officers,' say the authors.

'In an organisation that prided itself on paternalism

and care for its soldiers, the idea that regimental officers would

"oppress" their soldiers reveals only ignorance and prejudice.

'In the stem world of The Regiment, everyone lived by

a tough set of rules and understood uncompromising standards demanded.'

Yet despite those tough rules, which were common to

every army of the day, the number of British wartime executions was, in fact,

surprisingly small. From August 1914 to October 1918 there were approximately

238,000 courts-martial, resulting in 3,076 death sentences. But, of these, only

346 were carried out and 37 of them were for murder, which, at the time, would

of also have been punished by death in civilian Britain.

To put this in context, no fewer than 5,250,000 men

served in the British Army in World War I. Some 750,000 were killed

and 1,500,000 wounded. What

this means is that not far from the bleak barns, abattoirs, quarries and

embankments where just over 300 military offenders were put to death, some 400

equally frightened men were being slaughtered every day for doing their

duty without abandoning

their comrades. Discipline

in battle is not imposed just from the top. In war, deserters are looked on no

more kindly by their peers than by their officers. In 1914-18 courts-martial, the most damning

evidence nearly came.

from NCOs .and ordinary soldiers who witnessed the offence first- hand, not from their

superiors.

One Great War veteran, former Private Frederick

Manning, described the typical reaction of the troops. 'When Miller disappeared

just before the Hun attack, many of the men were bitter and summary in their

judgment of him.

'The fact that he had deserted his commanding officer

was as nothing to the fact that he had deserted them.

'They were to go through it while he saved his skin.

It was about as bad as could be, and if one were to ask any man who had been

through that spell of fighting what ought to have been done in the case of

Miller, there would have been only one answer. Shoot the bugger!'

Fortunately for the large numbers who were found not

guilty or had their death sentences commuted, the officers conducting

courts-martial in the field were not so hasty.

Though often young (especially as officer casualties

mounted) and completely inexperienced in legal procedure, they were usually

scrupulous about going 'by the book' - the formidable, red-covered, 908-page,

1914 edition of the Manual Of Military Law.

Defendants could cross-examine prosecution witnesses,

produce defence witnesses and ask for an officer, known as 'the prisoner's

friend', to represent them. Any previous offences were scrutinised only after a

guilty verdict, when the court came to consider sentence.

AN ESPECIALLY heavy sentence, such as death, had

to be unanimous, with the most junior officer giving his opinion first, so that he should not be influenced by his

superiors. After

a death sentence was passed, it was reviewed at each higher level of command,

collecting pleas for mercy or otherwise, all the way up to the

commander-in-chief who had to give the final confirmation.

In France and Flanders, that meant Sir John French or,

later, Sir

Douglas Haig. Far

from showing any gusto for the firing squad, these two famously formidable men

actually refused to confirm nine out of ten of the 3,000 death sentences placed

before them. In other words, the grim business that led to a wartime execution

was never lightly undertaken

Even in the heat of battle with justice conducted I

swiftly as possible in some shell ravaged French farmhouse by exhausted

officers, it is telling that there is not a single example of a man wrong

convicted of the offence with which he was charged.

Where there is room for argument is not over the

verdicts but the sentences. Judged by today's standards, there were some

disturbing decisions.

The chief difficulty lay in judging a man's mental

state when he committed a capital offence such as desertion or cowardice.

Military psychiatry had not been invented in 1914 A man was considered either

sane or incurably mad. There was no grey area.

By the end of that year, when the British

Expeditionary Force of 100,000 professional soldiers had suffered 96,000

casualties and experienced the mind-shattering hell of incessant shelling, fear,

mud, cold, rats and the stench of rotting bodies 24 hours a day, the authorities

reluctantly began to recognise there was such a condition as stress-induced

'hysteria' or shell-shock.'

But even-well-into the war, there was still a firm

view that those affected simply needed to 'pull themselves together'.

Private George Lawton was a Nottinghamshire man who

had responded to Kitchener's plea for volunteers when the bulk of the regular

Army had been virtually annihilated.

He had a good record as a soldier. But one July night

in 1916, he repeatedly refused to go on a sortie into no-man's land and was

charged with cowardice.

At his court martial, his defence was that since being

buried and wounded in a shell explosion in February, he was still 'suffering

from the effects'.

His written statement ended pathetically with the

words: 'Indeed, Sir, when our officer warned me to go out on a Fatigue Party, I

felt shocking nervous.'

Today, a medical officer might recognise behind this

piteous understatement signs of battlefield trauma. But Lawton displayed none of

the accepted physical signs of shell-shock, such as shaking or twitching

uncontrollably, and was pronounced 'in good health in every way'.

He was sentenced to death, but , with a recommendation

from his commander that it be commuted. Unfortunately General Monro, the

fierce disciplinarian commanding First Army, disagreed. Lawton was executed with

another member of his battalion, Bertie McCubbin.

McCubbin, too, had disobeyed orders to man a listening

post in no-man's land. 'I cannot do so,' he told the officer. 'My nerves won't

let me; if I go over I shall be a danger to the other man who is out there, as

well as to myself.'

HOWEVER reasonable that may sound to our ears, in 1916

it was considered even more reasonable - by soldier and civilian alike to charge

the man with cowardice in the face of the enemy.

At the court martial Pte McCubbin presented his

defence in the form of a touching letter. 'During my stay in the Annequin

trenches,' he wrote, 'I had my nerves shattered by a shell which burst on the

railway which runs above our trenches, 'bursting three yards away. I have never been

right since, my nerves being completely ruined.

'This being the case, I put the plea--forward that-my

case not being a blank refusal to an officer but as nervousness on my part being

made worse by the incessant bombardment which has been going on here lately.

'I have never been up before my company officer or

colonel before until now, this being the first time, and I have always tried to

play my part while I have been in the Army.

'I have also a father somewhere in France, leaving my

mother at home with six brothers and sisters, and always thinking if anything

had to happen to us two what would become of them, which does not

help me to get on a deal. 'So

I also put forward a plea that if you deal leniently with me in this case, I

will try and do my bit and keep

up a good reputation.' Like Lawton, McCubbin was found guilty and sentenced to death, with a

strong recommendation for mercy on account of his previous good character and

the state of his

health. This view

was echoed by other senior commanders, but once again Monro proved unbending.

'If toleration be shown to private soldiers who deliberately decline to

face danger, all the qualities which we desire will become debased and degraded.

He ruled. 'I recommend the sentence of the court be inflicted.

The two volunteer’s were shot at Lone

Farm on July 30, 1916, at 5am. McCubbin's death certificate contained the

chilling statement 'death was not instantaneous' - which suggests he would have

been finished off with a coup de grace from the officer's revolver.

By comparison with the case histories of most of the

other men executed during the war, these two were treated harshly.

What swung the decisions against them, apart from the

bad luck of having General Monro review their sentences, was that their offences

happened so soon after the catastrophic first day of the Battle of the Somme,

when the British

suffered 60,000 casualties. The high command was desperately

worried that what was by then a largely volunteer army would crack under the

strain, or even mutiny.

Leniency towards those who disobeyed orders at that

critical time would have sent the wrong signal to thousands of jittery men,

barely clinging to their sanity and courage in the trenches. In other words,

Lawton and McCubbin were made examples of.

Some other offenders had the balance of justice tipped

against them for the same reason, especially if they were NCOs or officers, or

had the misfortune to come from units whose moral fibre was thought to need

stiffening.

If a man was a poor soldier, his case was weakened. It

also seemed logical to make examples of the expendable, such as multiple

deserter, William Bowerman.

Approving the court's death sentence, Pte Bowerman's

brigade commander wrote bluntly that he was 'quite worthless, as a soldier or in

any other capacity and is better removed from this world'.

That must have seemed a shocking remark, even then.

But it was only an extreme example of a general tendency by senior officers to judge barely

trained volunteers and, after 1916, conscripts by the same rigid standards as

had applied to the regulars. This was harsh but understandable.

PERHAPS this knowledge helped some of them accept their fate.

The condemned man usually spent his last night writing letters and

talking to a chaplain. A

merciful Medical Officer would give him alcohol or opiates. At any rate, it is a

fact that most showed remarkable stoicism in the face of the firing squad.

A cavalry captain who witnessed an execution described

the scene.

'Before the prisoner arrived, the firing party had its

rifles mixed up and some of them unloaded so no one could be sure he had fired a

fatal shot. Then the 12 men were drawn up opposite a chair under a railway

embankment. The condemned man had spent the night in a nearby house.

'He walked from there blindfolded with the doctor, the

parson and the escort. He walked quite steadily onto parade, sat down in the

chair, and told them not to tie him too tight. A white disc was pinned over his

heart. He was the calmest man on the ground.

'The firing party was 15 paces distant. The officer

commanding the firing party did everything by signal, only speaking the word

"Fire!" the man's head fell back and the firing party about-turned at

once.

'The doctor said the man was not quite dead, but before the OC [officer commanding] the firing party could finish him