EDGES IN

CHINA

EDGES IN

CHINAOur Organisation is in the process of funding a Soup Kitchen in the diocese of Beijing. Because of the complexities of China, initially we will finance a hot meal one day each week for some of the poorest inhabitants of China’s sprawling city. We intend to start small. This is a new initiative in collaboration with the Diocese of Beijing

|

|||||||

|

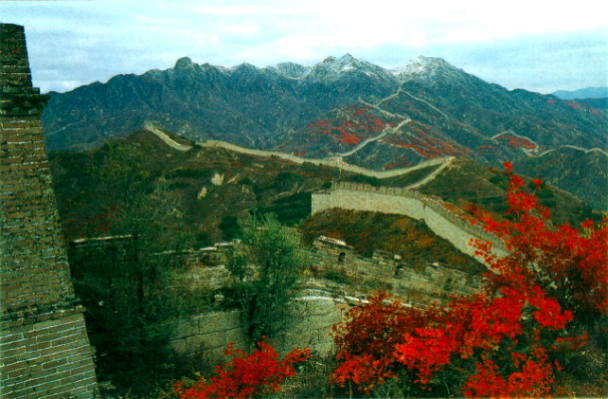

I arrive in the Diocese of Beijing in a country where priestly formation was completely forbidden from the middle of the 1960s until the late 1970s. In the October of 1949 the Chinese Communist Party proclaimed the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. From that moment on, relations between State and Church took a turn for the worse. The Communists viewed the Church as Western imperialism. Its atheistic ideology brought the country under the control of an anti God establishment. In the mid 1960s there was a period of total despair. All churches were closed, many of them demolished by the Red Guards and all religious activity had to cease. The Church is still picking up the pieces after this period of persecution. Church leaders and Christians were imprisoned and sent to labour camps. Archbishop Deng Yiming of Guangzhou Diocese writes in his autobiography "my days in prison were an extension of my Novitiate." The Chinese Church is filled with a people who have been exposed to suffering and turmoil. However, their faith has persevered. I meet with Father Peter Jianmin Zhao the Vice Chairman and Secretary General for the Catholic Administration Committee of the Diocese of Beijing. He speaks to me about the various teaching programmes that exist within the Diocese. The aim of these initiatives is to educate the people in the variety of Papal Encyclicals that Pope John Paul II has written over the last twenty years. There seems to be a love for the Institutional Church. I meet with some young adults who are part of a parish group run by Father Peter. Thirteen out of the fifteen are new converts. There is a hunger to belong to the Institutional Church. The reverse seems to be happening here in the UK. The more I communicate with people on our streets, the more I become aware that the Church in our country is entering a period of insecurity and confusion. Diocese are having to reassess their mission within a changing environment. Institutionalised religion is no longer attractive to the evolving youth cultures. God is not a feature on the agenda. However, in my work on the streets of central London and in our other major cities, I come across many young people who have a belief in God but will never sit in a church pew. This presents all churches with a great challenge. God is needed and we have to find the channel that can reach those areas that touch people’s lives. If we are to engage in this activity we need faith and perseverance. We can learn a great deal from our Chinese brothers and sisters. They are the contemporary witnesses of hope who did not give up in their time of despair. Since the transformation of religion in the 1980s, there is a Christian fever gripping towns, cities and villages. At a time of transition and breakdown of values, Christianity is now seen as a reference for reflection. It is also viewed as a bridge between an open China and the modern world. God is revealing a powerful message to us all that we must not give up in times of darkness, because the dawn of a new beginning is just around the corner. On the eve of World Aids Day, China conservatively estimated that it has around 500,000 HIV carriers. United Nations experts have warned of more than 10 million cases by 2010. The majority of China’s HIV carriers are to be found in the countryside where blood selling has contributed to its rapid spread. Much of the blood supply in China is not tested for HIV. Equally, there are around 30 million babies born in China each year, many thousands are abandoned when they turn out to be girls. These children often die from exposure, others are picked up by gangs and used for begging. The disposing and trafficking of human life has become a currency for the depraved and sinister Mafia style gangs that operate around the world. On the streets of Beijing I see small groupings of beggars, some as young as six years old, who plead for food and drink. However, compared with other cities in the developing world, real poverty seems to be hidden from the foreign visitor. Nevertheless, I’m told it is a real problem. It is incomprehensible how human life becomes so trapped and debilitated by the reality of existence. The eight stowaways found dead in a freight container in Co Wexford last week have invoked the memories of the fifty eight young Chinese who died of asphyxiation in the back of an airtight container at the port of Dover last year. China has its share of victims of oppression and poverty, especially, in the southern provinces. The remote and rural mountainous areas have been hardest hit. The Beijing government has pursued the rapid development of private industry and the dismantling of state enterprises with social provisions. This has created greater poverty for the Chinese peasants. In China I meet with many young people from the University of Beijing who long to visit Europe and America yet still have to struggle with the bureaucratic systems for visas. Some graduates wait years and are never told the reason why there is a delay. In the Western world we can take for granted the many freedoms that are bestowed on us. Imprisonment is not just confining someone to a building, we can become restricted by the circumstances of where we live and the conditions that greet us at birth. In China I met many people who are not Christian yet carry in their lives a warmth and hospitality that makes one feel welcomed. The majority have come from families who have struggled with poverty. Yet they have an abundance of wealth that is rooted in respect for each other. At times we cannot control our world. It can expose us to injustice and indifference. However, we are free to love or hate. One of the dangers in our western society is that we replace people with materialism. When this happens we run the risk of creating a fragmentation in our relationships where we become strangers instead of friends and we function at a distance with a superficiality that can imprison us. |