For information on surgical needles click here

Perineal repair is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. Despite changes in midwifery practice in the last decade, many women will sustain some degree of trauma during delivery and will require suturing. The majority of these wom en will experience some pain and discomfort during the immediate postpartum period, however, as many as 20% still have problems -such as dyspareunia - at 3 months. (Ref 1)

It is likely that both the technique of repair and choice of suture material have a direct bearing on the extent of the morbidity. Research has indicated that use of a synthetic suture material such as VICRYL* rapide (Polyglactin 910) or Coated VICRYL* (Polyglactin 910) together with a subcuticular skin closure technique reduces the level of perineal discomfort. (refs 1, 2)

Increasingly it is the midwife who will repair the perineum after normal delivery as part of the total care of the mother before, during and after labour.

The pelvic floor plays a vital role in supporting the pelvic organs. A good under-standing of the anatomy is necessary in order to avoid any long term complications, such as dyspareunia, urinary stress incontinence or visceral prolapse, arising from poorly approximated tissues. (ref 3)

There are three layers of muscles in the pelvic floor:

These muscles partly or totally surround an orifice and act as a sphincter when contracted.

The bulbocavernosus muscles form a loop partially encircling the vaginal orifice before passing forwards to the clitoris. They have a role in micturition and can aid contraction of the vaginal walls during sexual intercourse.

This pair of muscles compresses the veins at the root of the clitoris during sexual excitement, thereby producing clitoral erection through engorgement. They are unlikely to be involved in perineal tears.

This consists of a mass of fibro-muscular tissue separating the lower ends of the vaginal and anal canals. In cross-section it is triangular, with its base below. It is an important structure as it is the point of attachment of many other muscles in the pelvic floor and assists in fixing the position of the central perineal body. The levator ani muscles, the deep transverse perineal muscles, the bulbocavemosus and the posterior border of the triangular ligament all have fibres inserted into this muscle.

This is a two layered fibrous sheath situated between the symphysis pubis and the superficial transverse perineal muscle. Laterally it extends to the ischial tuberosities. (See figure 1.)

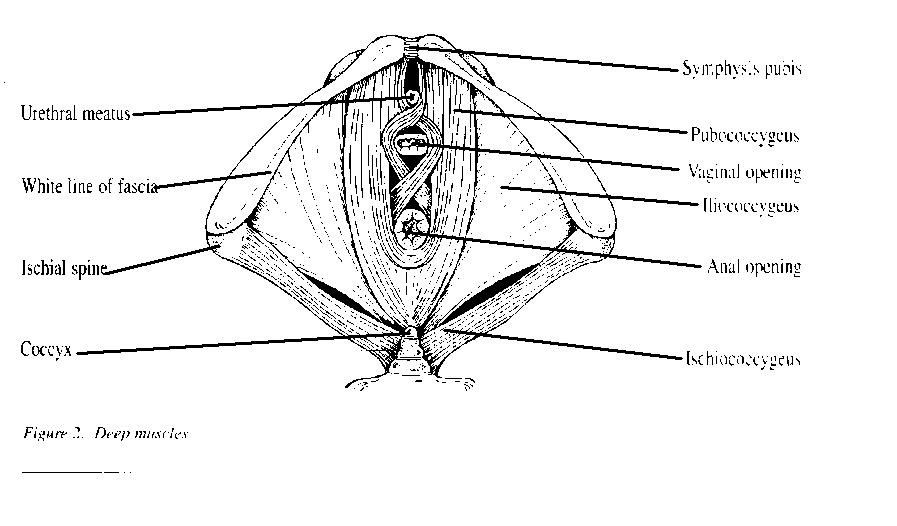

The deep muscles (levator ani muscles) form a sling to support the pelvic organs. There are three main components: the pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus and the ischiococcygeus muscle. They extend from the symphysis pubis, laterally to the ischial spine and posteriorly to the coccyx. Fibres cross over in the midline, encircling the vagina and blending with the rectum.

This muscle lies posterior to the pubic bone and extends to the lateral margins of the coccyx. Fibres of the pubococcygeus form U-shaped loops round the urethra, the vagina and the rectum. It is involved in sphincter control.

The iliococcygeus arises from the fascia on the lateral wall of the pelvis, blends with the pubococcygeus and is attached to the coccyx.

This has its origins in the ischial spine and extends to the last sacral segment and to the coccyx.

An episiotomy is the surgical incision designed to enlarge the vulval outlet during delivery. It involves:

There are two main directions of incision:

This begins at the mid-point of the fourchette and continues at a 45 degree angle to the midline (towards 7 o' clock). This incision reduces danger of damage to the anal sphincter and Bartholin's gland. It is the most common incision used in the UK.(ref 4)

This is a mid-line incision. It is associated with reduced blood loss, less pain and improved cosmetic appearance, but there is a high risk of damage to the anal sphincter if the incision tears further.

Spontaneous trauma is classified according to the structures involved. This ranges from first degree tears, which involve the posterior wall and perineal tissue only to third degree tears which include the anal sphincter and longitudinal muscle.

Once the instrument tray has been set up the mother's legs should be placed in stirrups. The vulva is swabbed with an antiseptic solution from anterior to posterior direction. A tampon may be inserted to stem the uterine blood flow. A small artery forcep should be attached to the tail. A thorough examination of the vagina and labia should be carried out to identify the extent of the trauma. If you are at all concerned, then a doctor should be informed, particularly if the anal sphincter or muscles are involved in the tear. Local anaesthetic (amount and strength depending upon unit policy) is infiltrated into vagina, muscle and skin edge. The full length of the needle is inserted into the tissue, ensuring that it has not entered a blood vessel and then the local anaesthetic is inserted as the needle is withdrawn. This is infiltrated into skin edges in a kite shape to ensure even distribution. Check that area is adequately anaesthetised before suturing commences.

Further information can be obtained by contacting ETHICON Limited Customer Services (Sutures) on 0131 442 5494.