.gif) William Strong Darby

William Strong Darby.gif) William Strong Darby

William Strong Darby

1821 - 1903

A VERY SHORT ACCOUNT OF THE VERY LONG LIFE OF WILLIAM STRONG DARBY

We do not know exactly when William

Strong Darby was born, but as he was baptised in St Michael's Church, Bishop's Stortford,

on the fourteenth of February, 1821, we assume it was not very long before that date, in

the first few months of the reign of the much despised and heavily corsetted former Prince

Regent, now King George IV. The baptism was a few weeks after the failed 'Cato Street'

conspiracy to murder the entire cabinet, and in the middle of the farcical Queen Caroline

'affair' ; the young poet Keats was a few days away from dying of consumption in an

upstairs room in Rome; and Napoleon was being slowly poisoned to death by his British

captors on faraway Saint Helena ---An epoch was drawing to a close. Fittingly, for a boy

who was to live to see the transition from 'Old England' to a recognisably 'modern' world,

William may even have been conceived in the dying days of the reign of poor, old,

"Mad" King George III, who had been on the throne, if at times unsteadily, since

1760.

The parties to that conception, however, remain something of a mystery : he claimed his

father was another William Strong Darby, who drove, or was the guard on, the Stortford to

London stage-coach operated by a Henry Gilbey, whose sons later founded the famous and

eponymous gin business. The unusual middle name, Strong, he attributed to long descent

from a medieval court jester

called Strong-in-th'Arm, who had a crest or coat-of-arms and a 'motto' to go with it. ( A

'likely story' --? Perhaps. Yet, there proves to be a deeper mystery to this harmless

romance than prudent scepticism would at first suggest. But that's another story - for

another day!)

We might suspect something of a 'jest' and a knowing wink to posterity when on his

marriage documents, our William states his father to be one William Darby, a

"whitesmith" -( that is, a smith who worked in tin and pewter, making and

mending pans and kettles - in other words, 'a bit of a tinker'). Perhaps he saw himself as

'forging' something of a 'white'-lie, as he gave these details to the

clerk : because his father would appear not to have been a Darby at all .......!

His baptismal entry in the Bishop's Stortford records states his father to have been

William Strong, a carpenter from London. His

mother was a local girl, Jane Darby. In the censorious phrase used by clergy at that time,

he was "Base Born"; the disapproval was as much a reflection of concern that

mother and child would become a burden on the rates as it was a moral issue. There was a

panic at that time about an epidemic of single mothers, many of whom were suspected of

getting themselves pregnant simply in order to be housed and financially supported 'on the

parish'. And in those days of horse-drawn travel and churned up roads, chasing up

probably pennyless putative fathers for child support, was considered a game scarcely

worth the candle.

Whether, and to what extent, this particular infant 'item of mortality' may have become a

'burden' on the parish is not recorded; but at that time, after five years of severe

economic depression following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the majority of poorer folk

received some form of 'relief' at some point during the economic cycle of the year.

However, following the usual practice of the time, in cases where the mother 'named', or

before a JP, 'swore to', the child's father, the father's surname was incorporated as a

second christian name, as a token of a claim by the child -and the parish- for support

from the father, should he be tracked down and found to be perchance in possession of a

tuppenny bit. Hence, William Strong Darby.

Of the mysterious father, William Strong we 'nothing know' : there had been Strongs in the

immediate area for centuries, and they were often carpenters, too - a William Strong had

worked as a carpenter repairing St Michael's Church three or four hundred years before our

William was baptised there. And there was a long tradition of carpenters from that corner

of Essex and Hertfordshire working as journeymen for house-builders in ever expanding

London. So he may well have been a local lad, but based and working in London. Perhaps he

had been home on a visit? Or perhaps Jane had herself been in service in London, and been

sent home when she was found to be pregnant? Certainly a team of carpenters had been

working on repairs to the church tower - where they left some 'interesting' graffiti

concerning the meanness of the parish big-wigs - in the months in which William was

presumably conceived.

About Jane Darby, or rather her background, we can speak with much more confidence. She

was of the Darby family of Great and Little Hallingbury, close on the Essex side of

Bishop's Stortford, where they had been village carpenters, wheelwrights, and husbandmen,

certainly since the 1670s, but possibly much longer. These small, rather 'scattered',

villages, were and are clustered round the ancient Hatfield Broad Oak Forest and the then

estates of the Houblon family. Though in many respects a secluded rural backwater,

the proximity of the Stort and Lee navigation, and the parallel busy coaching routes,

running through Bishop's Stortford, meant there was a constant to and fro of goods and

people between these communities and London.

William had said that his forefather

Darbys had worked with their neighbours, the Gilbeys, for some generations before Henry of

that name started his famous stagecoach, and that at one time, Darbys and Gilbeys had been

in that trade together. And indeed, Henry Gilbey's grandfather is found in the parish

register cheek by jowel with Darbys - he was Squire Houblon's forest keeper while the

Darbys were the local hedge and village carpenters, and --in a community of three hundred

or fewer souls-- they would at the very least have been well acquainted : the local

carpenters would have been required by the keeper to help erect and maintain the deer

fencing on the estate, and they would have  been involved in

the handling and preparation of the forest timber crop. Also, and at least consistent with

the coaching claim, in the last quarter of the eighteenth century the Darbys had tenure of

'The

George', on the parish border between Great and Little Hallingbury, a modest coaching

inn on the secondary route running down through Hatfield Heath. ('The George' is still in

business.

been involved in

the handling and preparation of the forest timber crop. Also, and at least consistent with

the coaching claim, in the last quarter of the eighteenth century the Darbys had tenure of

'The

George', on the parish border between Great and Little Hallingbury, a modest coaching

inn on the secondary route running down through Hatfield Heath. ('The George' is still in

business. Looking across the road, the

two acre field opposite - to the right of the old house called 'Bonningtons' -- was farmed

by the Darbys in the 1770's and retains the original hedge boundaries.)

Looking across the road, the

two acre field opposite - to the right of the old house called 'Bonningtons' -- was farmed

by the Darbys in the 1770's and retains the original hedge boundaries.)

Jane's precise position in this family is not clear, but we notice that other Darby

daughters around this time become pregnant by wayward carpenters-- Quite possibly Master

carpenters Thomas and William Darby had trouble keeping their journeymen and 'prentices

under adequate surveillance. But perhaps they shouldn't take all the blame : in nearby

Hunsdon, girls of the Darby family living there provided the parish with a considerable

portion of its 'base-born' burdens.

Sometime in the early 1800s the Darbys cease to appear in the Hallingbury records. It is

most likely they went the way of the majority of small husbandmen/artisans in those years,

gradually squeezed out of their holdings by engrossing landlords and wealthy farmers in

the war-time corn boom, and undercut by mass-produced articles as the industrial

revolution picked up steam (literally). Small holders were pauperised, and either became

the down-trodden agricultural labourers of the coming victorian period, or drifted to the

cities to become the urban working class. The same process occurs to the Darbys down the

road in Hunsdon, who are almost beyond doubt close collateral kin of the Hallingbury

family. Their 'patriarch', old Richard Darby, was buried in Hunsdon churchyard on the very

same day that our William was baptised --and one wonders whether Jane in her 'shame', or

at least embarrassment -- ("bloomin' pickle", she would probably have called

it)-- hoped the relatives would be out of town that day, for that reason?

William's boyhood was spent in Bishop's Stortford, and very likely in the household of

Sarah Darby from Hallingbury --probably Jane's sister, though possibly her aunt or cousin

--and her husband, James Carpenter. They would have received an allowance from the parish

to help with his upkeep. This would enable Jane to go away to work rather than further

burden the rates. It is, of course, possible that Jane had died, but there is no evidence

of this. James was also a carpenter by trade, in the lane behind the church, where they

were also socially 'close' enough to the nearby Tyler family to be witnesses at marriages

and so forth. The Tylers were the Stortford coachbuilders, and almost certainly maintained

Henry Gilbey's stagecoaches, as may have Mr Carpenter.

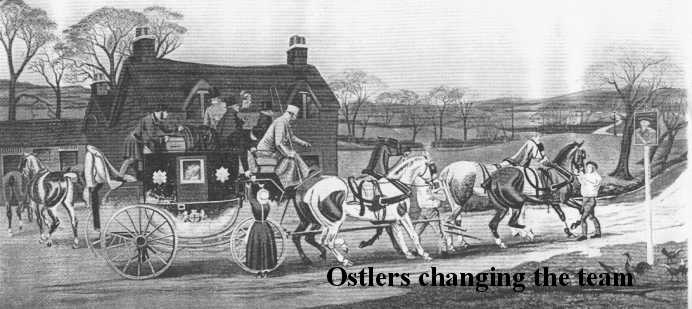

This was the 'golden age' of the stagecoach, the brief period between the making of the

improved turnpike roads in the 1790s and the dramatic coming of the railways in the late

1830s and early 1840s. All who were boys of that generation were enthralled by its

excitement and romance. Dickens, Thackeray, Thomas Hughes, (who wrote 'Tom Brown's

Schooldays'), all spoke of it in awed, even mystical, terms. Scarcely surprising, then,

that in old age, William spun tales of coaches and coachmen and 'four-in-hand'. But

especially as he almost certainly did have close contact with that world, and perhaps not

only through his connection with the Tylers and Carpenters, and seeing Mr Gilbey's London

stage sweeping past St Michael's Church on its way to Mrs Nelson's famous 'Bull Inn' at

Aldgate : for in the 1851 census, an elderly William Darby from Hallingbury --and very

likely Jane's brother -- was working as an ostler at the

'Duke of Wellington' coaching inn in Epping, which was a common occupation for a one time

driver or guard. At the very least we cannot lightly dismiss there being a strong, albeit

embellished, factual core to William's story of his "father" 'blowing the

horn" on Gilbey's stage. (The horn wasn't just for show or to warn people to get out

of the way of this on-rushing ten miles-an-hour whirlwind, it was to alert the ostlers at

the next stop to have the new team of horses ready in the yard for a lightening change

over --and in the case of a Mail-Coach, for the postmaster to have the mails ready for

collection.) It was every boy's dream to ride 'on the box' with a stagecoach driver -(and

rich young swells paid large amounts for the privilege, and even more to take the reins) -

but in William's case, he may well have done so, gratis, courtesy of relatives or friends.

was working as an ostler at the

'Duke of Wellington' coaching inn in Epping, which was a common occupation for a one time

driver or guard. At the very least we cannot lightly dismiss there being a strong, albeit

embellished, factual core to William's story of his "father" 'blowing the

horn" on Gilbey's stage. (The horn wasn't just for show or to warn people to get out

of the way of this on-rushing ten miles-an-hour whirlwind, it was to alert the ostlers at

the next stop to have the new team of horses ready in the yard for a lightening change

over --and in the case of a Mail-Coach, for the postmaster to have the mails ready for

collection.) It was every boy's dream to ride 'on the box' with a stagecoach driver -(and

rich young swells paid large amounts for the privilege, and even more to take the reins) -

but in William's case, he may well have done so, gratis, courtesy of relatives or friends.