|

A fresh hope is astir. From many quarters comes the call to a new kind of education with its initial assumption affirming that education is life—not a mere preparation for an unknown kind of future living. Consequently all static concepts of education which relegate the learning process to the period of youth are abandoned. The [Page 5] whole of life is learning, therefore education can have no endings. This new venture is called adult education— not because it is confined to adults but because adulthood, maturity, defines its limits. The concept is inclusive. The fact that manual workers of Great Britain and farmers of Denmark have conducted the initial experiments which now inspire us does not imply that adult education is designed solely for these classes. No one, probably, needs adult education so much as the college graduate for it is he who makes the most doubtful assumptions concerning the function of learning. Secondly, education conceived as a process coterminous with life revolves about non-vocational ideals. In this wor1d of specialists every one will of necessity learn to do his work, and if education of any variety can assist in this and in the further end of helping the worker to see the meaning of his labor, it will be education of a high order. But adult education more accurately defined begins where vocational education leaves off. Its purpose is to put meaning into the whole of life. Workers, those who perform essential services, will naturally discover more values in continuing education than will those for whom all knowledge is merely decorative or conversational. The possibilities of enriching the activities of labor itself grow less for all workers who manipulate automatic machines. If the good life, the life interfused with meaning and with joy, is to come to these, opportunities for expressing more of the total personality than is called forth by machines will be needed. Their lives will be [Page 6] quickened into creative activities in proportion as they learn to make fruitful use of leisure. Thirdly, the approach to adult education will be via the route of situations, not subjects. Our academic system has grown in reverse order: subjects and teachers constitute the starting-point, students are secondary. In conventional education the student is required to adjust himself to an established curriculum; in adult education the curriculum is built around the student’s needs and interests. Every adult person finds himself in specific situations with respect to his work, his recreation, his family-life, his community-life, et cetera—situations which call for adjustments. Adult education begins at this point. Subject-matter is brought into the situation, is put to work, when needed. Texts and teachers play a new and secondary role in this type of education; they must give way to the primary importance of the learner. (Indeed, as we shall see later, the teacher of adults becomes also a learner.) The situation-approach to education means that the learning process is at the outset given a setting of reality. Intelligence performs its function in relation to actualities, not abstractions. In the fourth place, the resource of highest value in adult education is the learner’s experience. If education is life, then life is also education. Too much of learning consists of vicarious substitution of some one else’s experience and knowledge. Psychology is teaching us, however, that we learn what we do, and that therefore all [Page 7] genuine education will keep doing and thinking together. Life becomes rational, meaningful, as we learn to be intelligent about the things we do and the things that happen to us. If we lived sensibly, we should all discover that the attractions of experience increase as we grow older. Correspondingly, we should find cumulative joys in searching out the reasonable meaning of the events in which we play parts. In teaching children it may be necessary to anticipate objective experience by uses of imagination but adult experience is already there waiting to be appropriated. Experience is the adult learner’s living textbook. Authoritative teaching, examinations which preclude original thinking, rigid pedagogical formula—all of these have no place in adult education. "Friends educating each other," says Yeaxlee, and perhaps Walt Whitman saw accurately with his fervent democratic vision what the new educational experiment implied when he wrote: "learn from the simple—teach the wise." Small groups of aspiring adults who desire to keep their minds fresh and vigorous; who begin to learn by confronting pertinent situations; who dig down into the reservoirs of their experience before resorting to texts and secondary facts; who are led in the discussion by teachers who are also searchers after wisdom and not oracles: this constitutes the setting for adult education, the modern quest for life’s meaning. But where does one search for life’s meaning? If adult education is not to fall into the pitfalls which have [Page 8] vulgarized public education, caution must be exercised in striving for answers to this query. For example, once the assumption is made that human nature is uniform, common and static—that all human beings will find meaning in identical goals, ends or aims—the standardizing process begins: teachers are trained according to orthodox and regulated methods; they teach prescribed subjects to large classes of children who must all pass the same examination; in short, if we accept the standard of uniformity, it follows that we expect, e.g., mathematics, to mean as much to one student as to another. Teaching methods which proceed from this assumption must necessarily become autocratic; if we assume that all values and meanings apply equally to all persons, we may then justify ourselves in using a forcing-method of teaching. On the other hand, if we take for granted that human nature is varied, changing and fluid, we will know that life’s meanings are conditioned by the individual. We will then entertain a new respect for personality. Eduard C. Lindeman (1926) The Meaning of Adult Education, New York: New Republic. First published September 2002. Last update: January 31, 2005 |

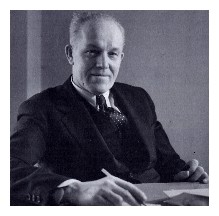

Eduard

C. Lindeman (1885

- 1953) worked across traditional subject

borders. He was a professor of social work, but he is perhaps best known for

his work around adult education, especially his book The

Meaning of Adult Education (1926). He also produced early texts on community and community

organization (1921), and on working with groups (1924). Eduard Lindeman also wrote about

social research (1933 with John Hader) and social education (1933).

Eduard

C. Lindeman (1885

- 1953) worked across traditional subject

borders. He was a professor of social work, but he is perhaps best known for

his work around adult education, especially his book The

Meaning of Adult Education (1926). He also produced early texts on community and community

organization (1921), and on working with groups (1924). Eduard Lindeman also wrote about

social research (1933 with John Hader) and social education (1933).