INTRODUCTION

`Charisma' is a Greek word meaning `a

gift', and `charism' was a power to perform miracles

conferred on the early Christians. A ' few people have

charisma, and so do a few machines. Two British examples

of the latter having it in abundance are the Spitfire

aeroplane and the E.R.A. racing car, both evolved in the

nineteen-thirties. Neither was overwhelmingly better than

its contemporaries, but both were products of enthusiasm

and private enterprise and both seem to have had a power

conferred upon them to achieve an eminence in future

years which can hardly have been anticipated by their

originators. Indeed, anyone who admits to having driven

an E.R.A. or flown a Spitfire is certain to invite a

wholesale breaking of the tenth commandment by less '

fortunate mortals who have not had the experience. It is

tribute enough to the E.R.A. that nearly fifty years

after its birth David Weguelin, who is too young to ever

have seen E.R.A.s performing in their heyday, has had the

incentive to go to , immense trouble to compile this

detailed history of the marque and has found publishers

with the enthusiasm to launch his work ' in the form of

this beautifully produced and lavishly illustrated book.

In these days when an average family saloon can

outperform ' many a vintage racing car (though not all of

them, I am glad to say!), it might be thought that

driving an E.R.A., which is only slightly newer, yet

still very nearly fifty years old, cannot be so very

thrilling. This is not so for several reasons, one being

that even by modern standards an E.R.A. is fast, being

capable of at ... least 125 mph (some nearer 150mph) with

acceleration to match, ' but the suspension is hard and

the roadholding on the primitive side. Perhaps the latter

factor is not so significant on modern circuits because,

paradoxically, as racing car suspension improves '. so

surfaces are getting smoother and the circuits are made

to suit the cars with great precautions taken not to

upset them and their drivers in both senses of the word.

Today there are very few `natural' circuits left. It is

some twenty years since I myself first drove an E.R.A.,

the 2 litre RllB, one of the faster examples of the

marque, and perhaps what I wrote about the experience at

the time in a book now long out of print called `Racing

an Historic Car' may be of interest. It happened on the

Silverstone Grand Prix circuit.

`I went slowly round Woodcote, and then opened the

throttle and felt I ,was being hurled forward by a

typhoon. Of course one gets used to anything, so it is

one's first few laps in a racing car one should try to

remember. Everybody has experienced that feeling in a

low-powered car

of putting one's foot hard down in the throttle, and

waiting for something to happen.

In the E.R.A. it always happened before I was ready for

it and, at first, accelerating away

from a corner was like being on a runaway horse, I was

not really sure I wanted to be getting away from the

corner at such a rate of knots. Rounding Chapel Curve, I

felt myself experiencing what seemed to me excessive

"g" for the first time in a car, through being

pushed hard back in the seat when accelerating, and

pre-selecting the gears going down Hangar Straight was

difficult for two reasons; firstly, putting one's hand

out to grab the lever was like putting it into the

slipstream of a Tiger Moth, and secondly it was so bumpy

that it was difficult to get hold of the lever anyway. It

was all so completely fascinating that it was hard to

persuade oneself to stop. Not once on that particular day

did I have the throttle hard on the floor and hold it

there, and so far as the wide open spaces of airfield

circuits are concerned, to me it seemed an endless

succession of corners, except for Hangar Straight, which

was the only place I got into top gear. I found the

pre-selector box took a little getting used to as instead

of changing gear in one complete movement it is actually

two separate ones.' Raymond Mays was a pioneer in several

aspects of motor racing which are accepted as normal

today, and E.R.A. was the first small British firm

specialising in the exclusive manufacture and sale of

racing ears. Geoffrey Taylor, of Alta, came in much the

same category, but he started by making a sports car and

was also a sports car manufacturer, though on a very

small scale. To him must go the credit for designing and

building his own engines, though they were less

successful than the Riley based E.R.A. engines in the

pre-war days. A Connaught fitted with an Alta engine won

the 1955 Syracuse G.P. with Tony Brooks at the wheel, for

few of the British specialist racing car constructors of

later years designed and built their own engines, B.R.M.

and Vanwall being exceptions. Mays must also have been a

pioneer of sponsorship, seeking backers for his racing so

that he could continue competing, his sponsors being

connected with the motor accessory trade, yet he himself

was a great advocate of the ethos of amateurism in sport.

On his own admission, he certainly did not enjoy trying

to talk to people into backing him.Today in every sport,

including motor racing, a single minded dedication to

succeed is the norm, and everybody seems to have the will

to win in super abundance, a stimulus, no doubt, being

the big financial rewards involved. Mays had this will to

win, partly because it was a natural part of his make-up,

but also because when he had backers he had a fear of

letting other people down. Mays, like the E.R.A.s, had

charisma as did two other young men who brought a great

deal of glamour to motor racing and to E.R.A. before the

war, the Siamese royal princes Prince Birabongse

Bhanubandh and his cousin Prince Chula Chak- Rabongse,

the former doing the driving and the latter the managing

all on an amateur basis. However, one has only to read

Prince Chula's books about their racing experiences to

realise the will to win was tremendous and his

organisation was, in fact extremely professional. Less

professional conduct, perhaps, took place on the occasion

when Bira drove his newly acquired E.R.A. `Romulus' from

its garage in Dieppe out to the circuit early one July

morning to practise for the 1935 Dieppe G.P., his first

race in the car, only to lose his way and drive round and

round the town looking for the right road! To make up for

this, though, he did finish second in the race,

convincing proof that he eventually found where the

circuit was. The driving of the E.R.A.s on public roads

is always a fascinating subject, whether within or

without the law, and several instances of it are given in

this book. The best known recorded cases in this country

are the excursions by the works cars for testing purposes

on a circuit near Bourne, and Mays's drives in 2 litre

cars to Shelsley Walsh for the autumn, 1934, meeting and

to the docks at Harwich for shipment to the continent for

the 1935 German G.P., both from the works at Bourne. The

longer journeys were evidently legal by courtesy of

`small wings, a hooter and a large fishtail', the testing

sessions on the deserted fen roads less so. In recent

years when Peter Waller owned R.9.B. he discovered that

the famous former racing driver Denis Poore was a

neighbour of his in the country, and obviously the only

suitable transport which to pay him a visit was the

E.R.A. Unfortunately ever time he arrived at the Poore

residence the owner was out, and the gardener could not

make out who this eccentric man was who kept turning up

in this very noisy car with only one seat in it asking

for Mr. Poore. On another occasion a Vintage Sports Car

Club member, who had better be nameless, had been working

on his E.R.A., which still had its racing numbers on it

from the last event it ran in, and he could not resist

taking it `round the block' a couple of times for a test

in a semi-rural area. Unfortunately he disturbed an old

lady who rang the police to complain that a red racing

car had passed her house twice making a terrible and

obviously illegal noise. Did you get its number?' asked

the policeman. `Yes,' said the old lady,`it was no. 7.'

And, on the subject of noise, surely to the enthusiast

the sound of a well tuned E.R.A. is one of the most

thrilling sounds in the world, unparalleled for me even

by that deep rumble of the Monoposto Alfa Romeo (the

`P3') or the calico tearing sound of a Bugatti,

marvellous though the latter are. I was thirteen years

old when the first E.R.A. was made, at that time a motor

racing enthusiast of some five years' standing, and made

every effort to attend race meetings, whether it was by

bicycle to the Crystal Palace, by car to Donington Park

with members of my family, by car or train (if I was on

my own) to Brooklands, it being possible to buy a

combined rail and Brooklands entrance ticket from

Waterloo to Weybridge. In those days I could distinguish

a11 the drivers of E.R.A.s, partly by the racing clothing

they wore, but mainly by their attitude at the wheel, for

it was all very highly personalised, unlike today when

modern racing car drivers are hidden in their cockpits,

and thus are virtually indistinguishable from each other.

My actual contacts with racing drivers were few and

rather ephemeral. I once pushed Teddy Rayson's Maserati

with several other volunteers in response to his cheerful

exhortations in the paddock at Brooklands, and Michael

May, a leading amateur Alvis driver who gets a mention in

this book, actually saluted me once. This was when,

having just passed my driving test, I was at the wheel of

my father's 192712/50 Alvis saloon following the veterans

on the Brighton Run, and M. W. B. May approached from the

opposite direction driving another vintage Alvis. Despite

a fairly long service career which followed, this was

easily the most memorable exchange of salutes I ever

experienced. It must have been in 1943 that I went to a

party in Newcastle-upon-Tyne as a newly qualified R.A.F.

Sergeant-Pilot which resulted from meeting some complete

strangers in a pub, the hospitality being tremendous in

that part of the world. During the evening a friend of

mine who was also invited said `Do you know there is an

E.R.A. driver here?', and before long I was speaking to

ari Army Captain called Dennis Scribbans, who I had

watched win his first race, the final of the British

Mountain Championship, in his newly acquired cream

coloured E.R.A. R.9.B. at Brook-lands at Easter, 1936.

This was the last race of the day and when it was over i

well remember it became cold and rather misty, and the

slight sense of depression this brought with it almost,

but not quite, overcame the magic of being at Brooklands.

My memory of Dennis Scribbans is now rather hazy, but I

do remember being impressed by the fact that he arrived

at the party on a motor cycle and sidecar combination

which he parked in the front garden. Reverting to Teddy

Rayson again, in the nineteen-sixties I became a flying

instructor at Cambridge University Air Squadron, and on

the board in the hall of the Squadron headquarters in

Chaucer Road bearing the names of C.U.A.S. members who

had been killed in the R.A.F. in the second world war was

inscribed the name `E. K. Rayson'. Like thousands of

others I had a desire to race an E.R.A., but the snag

with motor racing is that cars change over the years, and

thus so does the sport, unlike football or cricket which

are always much the same as the participants only bow to

the march of progress by wearing shorter shorts in the

one case and harder hats in the other; but a small boy

who wished to emulate Bob Gerard in his E.R.A. in 1948,

would find to his bitter

disappointment that by the time he was old enough to be

able to afford to race all the single-seaters had the

engines at the wrong end, superchargers were

unfashionable, and there were no courses on which he

could race over tramlines and past pillar boxes.

Fortunately the Vintage Sports Car Club has come to the

rescue of all such people suffering from arrested

development, and although the V.S.C.C. organisers cannot

now use circuits with the aforementioned natural hazards,

at least they have continued to put on races for

out-of-fashion cars like E.R.A.s, thus serving to keep

them very much in fashion. As this book shows, the

majority of pre-war E.R.A. drivers were amateurs, many of

them `garagistes' of one sort or another, but others had

quite different occupations, Bira had his sculpting and

Billy Cotton his dance band leading. In that entertaining

book Motoring is my Business John Bolster wrote: `Your

genuine professional driver, who really does make racing

pay, is an extremely rare bird. He must be obsessed with

one thing, yet he must keep both feet firmly on the

ground. In general, he may be a bit of a bore, because he

has no time to take an interest in art, literature,

politics and the thousand and one things which make a man

an attractive companion. There are exceptions, of course

. . .' V.S.C.C. racing has always been completely amateur

(`You must keep it amateur', Raymond Mays once advised

me, in my capacity as Secretary of the Club), yet it has

produced some extremely skilled E.R.A. drivers. Few will

forget the performances of W. F. (Bill) Moss in the

fifties at the wheel of `Remus', although he was less

successful after selling `Remus' to the Hon. Patrick

Lindsay and going on to compete with modern cars. Patrick

Lindsay's driving of the same car over the last twenty

years will surely become legendary, and he gets faster as

the years go by. As he also flies his own Spitfire, he

must be the personification of all that `charisma' brings

with it. E.R.A.s today are valuable property, and even

with inflation are expensive compared with the £750

which my brother Douglas and I and Arthur Jeddere-Fisher

had to club together to find in order to buy R.ll.B. in

1958, complete with an old Bedford bus used as a

transporter on which the front registration number

differed from that on the back by one. However, most of

the

E.R.A. drivers in the club have owned and raced their own

cars for a long time and the majority can hardly be

described as rich men. Most do their own maintenance, and

many camp beside their cars at meetings. Courses have

improved over the years and have become faster, but as I

write in 1980 one record held by an E.R.A. in the hands

of a V.S.C.C. member is worth recording, 43.42 sec's over

the old course at Prescott by Sir John Venables-Llewelyn

in the 2 litre R.4.A. Perhaps the E.R.A. wins in the

V.S.C.C.'s premier race, the Richard Seaman Memorial

Historical Trophy race over the last 30 years give a good

birdseye view of E.R.A. activities in the V.S.C.C. The

cars with the most wins, eight each, are `Remus' and

R.ll.B., the latter always a 2 litre, but `Remus' was not

raced as a 2 litre until his win in 1980. Two of

`Remus's' wins were with Bill Moss at the wheel, six in

the hands of Patrick Lindsay, whilst Martin Morris in

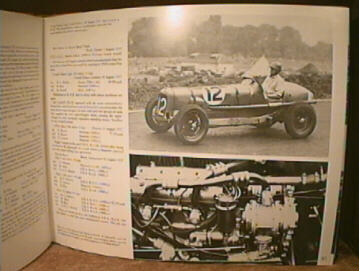

R.ll.B. achieved seven wins and Douglas Hull one. R.l4.B.

with Jimmy Stuart has had one win, as have R.2.A. with

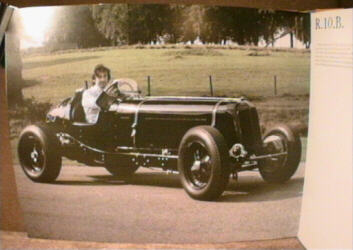

George Harwell, R.lO.B. with Jack Williamson, and

"Hanuman" , R.12.B., with David Kergon. R.6.B.

has had two wins in the hands of Sid Day, and R.9,B. has

also had two wins driven first by Peter Waller and then

by Chris Mann. All the `A' and `B' type cars, except

R.3.B. which crashed in 1936, still exist, and all have

raced with the V.S.C.C. over the years. The most romantic

E.R.A. story in the last three decades was the result of

Narisa Chakrabongse's decision to race `Romulus' again

after his long retirement, his restoration and conducting

being placed in the very capable hands of Bill Morris,

who is no relation to Martin Morris, as Donald Day is no

relation to Sid Day. Thus `Romulus' has only ever been

raced by two drivers, Bira and Bill Morris. Here is a

book, then, which records the complete E.R.A. story in a

most meticulous, yet frequently amusing, manner from 1934

to 1951, with detailed histories of all the cars. The

author and the whole editorial team have done a

remarkable job, a most commendable aspect being the

tracking down and interviewing of various people

connected with E. R. A.s in the past. It will be

rewarding browsing material, and I have learned a great

deal from it, not necessarily connected with E. R. A.s,

e.g. I could not believe my eyes when I read that Percy

Maclure raced a 999 c.c. Riley at Donington in 1936, but

sure enough a bit of checking up revealed he was running

with an experimental 1 litre engine. I am sure I am not

the only person who is grateful that an unusual story of

endeavour-and a British one, at that-has at last been put

between the covers of a book for the benefit of past,

present and future enthusiasts who cannot help but admire

those apparently ageless racing cars - the E.R.A.s

PETER HULL

|