|

CHAPTER 7. THE RECTORY, GLEBE AND TITHES |

This chapter deals with the support of the clergy. In the past, Rectors were not salaried, but held property in the parish as their "living". The Rector was expected to live on the proceeds from this property. Sometimes termed "The "Parson's Freehold", the property had three parts: the rectory (house, outbuildings and yard), the glebe (an area of land to be farmed for the rector's personal profit), and the tithes (essentially taxes or produce associated with each parcel of land in the parish, payable by the landowner to the rector; at Cranham the Lord of the Manor was exempt). The Rector held his property as a legally valid freehold whilst he served the parish; however the property automatically transferred to the next Rector upon his appointment. It is a rare legal example of a freehold that cannot be sold, donated, bequeathed, or inherited. In this chapter, we shall look into the history of these three components in the Parson's Freehold at Cranham.

Before 1923, the rectory stood at grid reference TQ571(7)869(0). It was surrounded by the glebe. Rectory Gardens and Glebe Close are modern housing developments occupying the site (4).

The earliest reference to the Rectory is 1686 (103). This report, signed by the Rector, churchwardens and others, contains a description of the parson's freehold, and some details about the Rectory itself:

"A terrier of all and singular the house, outhouses, edifices, buildings, and lands both arable and pasture, ... exhibited to the Reverend Archdeacon of Essex the 12th day of April, 1686".

"A parsonage house, together with a barn and stable standing northwest from the said parsonage house, also another barn with a cow house thereto adjoined standing in the great yard on the west side or end of the said parsonage house. An orchard and a garden containing together about an acre of land."

We have no idea what this rectory looked like, although the arrangement of buildings is shown on the Ordnance Survey map of 1844 see Figure 24 (238). The Victoria County History says that it was rebuilt in 1790 (12); however, this must be doubtful because 1790 was the same year as the rebuilding of Cranham Hall, and no other references to this rebuilding has been found.

In 1889, the rectory was described as:

"A large Rectory house with the usual offices, coach house adjoining, large barn with stable. In connexion pigstyes, fowl houses, large shed for cows, etc. partly enclosed all round. Cottage for a man within premises with cowhouse adjoining, usual offices."

Thomas Ludbey lived in this rectory, and made three entries about it in the vestry minutes. It is disappointing that these were about relatively minor elements in the construction. Figure 23 shows one of these notes.

The second note describes the unsavoury business of emptying the cess pool (104):

"On the might of the 8th November 1834, the servants' privy was emptied by Elliston, a bricklayer of South Ockendon (generally employed by Mr.Hammond), his son, and William MacMillan. It was done in one night for one pound.

Under the stones, immediately in front of the door is a brick arch, covering some steps which lead into the reservoir, which is large enough to hold a mudde waggon full. Till the night above mentioned it had not been open many years, certainly not during my incumbency (16 years).

[signed] Thomas Ludbey."

If they divided the money equally, then this was about a week's wage for a night's work. The place to where the product of this emptying was disposed of is not recorded.

The third of Ludbey's notes is quite long, and dated November 5 and 6, 1840 (104). Another cess pool was the subject, this time beneath the brewhouse. Ludbey measured it to be 3 feet by 3 feet by 7 feet deep, and that a drain to it, "large enough to admit a boy", ran under the two pantries. This, too, was cleared at the cost of one pound. Of all the things he might have chosen to record, one wonders why Ludbey was so fascinated by the subject of clearing out cess pools.

This rectory was described as large, even by those who were conducting a survey of all the church property in Essex. We hear directly of a drawing room, two pantries, a brewhouse, a coach house, and numerous farm buildings. In addition, there was a cottage and outhouses for servants. Even though large, the rectory was an unspectacular example of a common type of building.

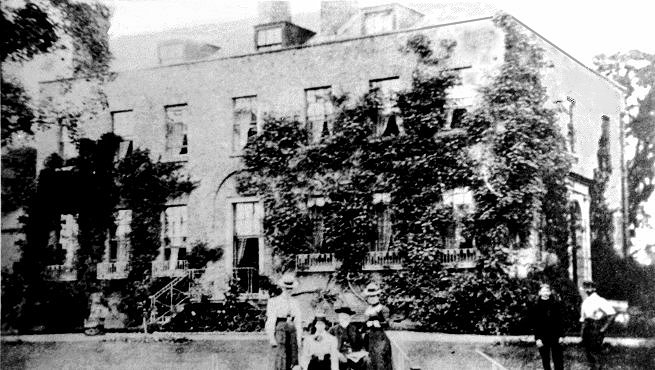

|

| The Reverend Cooke and his household at Cranham Rectory in 1904. |

Likewise, when Newcombe walked through the parish in 1903 (215), he wrote:

" Generally in this walk, we shall find few examples of domestic architecture beyond average interest, except the remains of Cranham Hall."

The end of the Front Lane rectory came in 1923. Dr.Wright was appointed as Rector that year, and by this time, Rectors drew a salary. Wright thought that the Rectory was too large for his real needs, and it was decided to sell. The proceeds were used to build a new house at the top of the Chase, near the church, standing on an acre of ground. A square parcel of land was retained at the junction of St.Mary's and Front Lanes, and a church hall was built upon it (TQ571(8)867(0)). Quite apart from the quality of the new buildings, this sale gave stability to the churchwardens' accounts for many years to come, and especially during the difficult years of the 1920's and 1930's. Dr.Wright served Cranham for 30 years from his new Rectory, and must take great credit for this progressive move.

|

The rector as farmer: An auction of the Reverend

Cooke's possessions in 1905. The 'very capital powerful black mare' sold for

£27/6/= and the cows, an Alderney cross breed, for £27/6/= and a 'shorhorn' for £11.

In contrast, the grand piano, a six and a half octave instrument in a fine rosewood

case by Erard went for £4/5/= while somebody paid half a crown for a stuffed parrot! (from the collection of Ruby Witham, by permission.) |

The house of 1923 still stands at TQ572(0)862(6). It is impressive, of three stories, and has a neo-Mansard roof. Whilst in use as a rectory, the arms of St.John's College, Oxford hung above its front door as a visible notice of the Patron. Ivy grew on its front until recently. The size of its garden permitted Father Bowen, in the late 1960's and early 1970's to accommodate camping Cub Scout packs, and even church fetes.

In 1985, the Rectory up the Chase was again judged to be too large for the needs of the parish. It was sold to a private person, and the coat of arms from the front was given to an historical society in Georgia, called The Friends of Oglethorpe. Reverend Pages now lives in Ingrebourne Gardens, amongst his parishioners, rather than at the top of the hill.

The first reliable reference to the glebe is again the Archdeacon's terrier of 1686 (103):

"Of the glebelands, there are (according to the computation of the 16 foot pole) reputed to be 33 acres divided into severall parcells both arable and pasture".

The document goes on to define where these lands lay, and whether the parson or the neighbour was responsible for fencing. The terrier also notes that most of the ground was rented to a widow named Mary Weveslure and a husbandman (animal keeper) called James Tarling. The rents are not recorded. Figure 26 shows where these 33 acres were.

Since 1686, records of the size of the glebe have varied (Table 7). these probably represent errors of estimation rather than actual gains or losses of land. The tithe map (4) and the Ordnance Survey map (6) support a total area very close to 33 acres. The square retained for the church hall was about 1 rod, or a quarter of an acre. Some glebe must have been lost to the Upminster to Grays railway in 1892 (see Chapter 14), but this is less than an acre.

The church hall site was sold in 1965. A pill box (presumably to defend the crossroads in case of invasion) was there from about 1942. Two private homes now occupy the site.

Arguably, the glebe now comprises only the Boyd Hall, its yard, outbuildings, and Turnpenny's field at the rear. The story of the acquisition of this old school by the parish is told in Chapter 12 (see figure 33). Turnpenny's field is rather overgrown, much to the delight of the Scouts and Cub Scouts that use it; it is about half an acre, and was bought in 1970. The school house is rented by the parish.

Tithes were originally supposed to be for the support of the poor, and the monies to be collected and controlled by the Rector. This system of parish relief, supported by the landowners through tithes, was supposed to be of mutual benefit: a supply of labour was ensured when needed, whilst the labourers could subsist without wages when idle.

The next development in parish relief was the introduction of a Poor Rate in the eighteenth century. The intention was the same: labourers were guaranteed to be available when needed, and would not leave the parish when laid off. The tithes were not abolished at this time, and quickly became a form of salary for the Rector. Not surprisingly, being paid but not controlled by the landowners, tithes became a source of friction in many parishes; Cranham was no exception.

In 1771 (107), Muilman noted that the tithes at Cranham were worth about £1-7-4 d. per annum. The clergy were at liberty at this time to accept cash in lieu of actual produce from each field, but this was not a legally guaranteed procedure.

Strahan fought for his tithes during several years towards the end of the eighteenth century. Strahan was a pluralist, holding several parishes at once, and he employed four curates at Cranham. Even so, during his tenure, the registers bear the signatures of clergymen from all around the district. It was probably the lack of performance on the part of the Rector, that especially made the parishioners resent the payment of tithes. Between 1785 and 1805 many lawyers bills were paid by both the Rector and the parishioners for legal actions (109), and on one occasion, in 1794, the parishioners travelled to London to seek the opinion of a barrister named Mr. Menah (109). No actual court appearance resulted, so one assumes that compromise was reached on each occasion.

In 1805, the parishioners tried a new tactic to avoid the tithes: organized rebellion. They met at "The Bell" public house in Upminster on June 14, which was about 10 weeks before the harvest. They then jointly issued a documents, signed by them all (108; Figure 27). The content may be summarised as:

The unrest over tithes was widespread, and Parliament eventually considered the matter. The Tithes Commutation Act (1839) required that independent commissioners should be appointed in each county, and that they would report on the owner, occupier, and value of every piece of land. The tithes would be calculated as a cash payment from this valuation. With this new cash-based system, it would then also be possible for the Rector to accept an immediate, one-time payment in respect of all tithes in the future. Neither parishioners nor Rector would be able to enter into negotiations: the amounts to be paid would be fixed, once and for all.

The local Tithe Commissioner was based at Langdon Hills and surveyed many of parishes in the area; he reached Cranham in 1840. His map was the greatest benefit to the local historian. He drew the entire parish at a scale of 25 1/2 inches to the mile. The sheet is six feet long and three feet wide. Every piece of land is detailed, including bits of waste alongside the roads. The owner and occupant (if the owner rented it out) of every field, orchard, strip, green, pond, and road was recorded. It is a beautiful map.

Overall, in Cranham in 1840, there were 1875 acres of land under cultivation. The rectory and glebe comprised 33 acres, or just under 2 % of this land. Another 37 acres were designated "roads and waste". This yielded, to the Rector, the annual sum of £560, in lieu of the produce. Although a large sum, this was fixed. Inflation could not alter this in the future. Presumably, the parishioners compared this to their previous costs in tithes and money spent on lawyers.

This cash system lasted for almost another century. By 1935, these sums of money had become less significant, and many annual tithes had been settled by a lump sum payment for ever. In 1935, the tithes were abolished completely (178).

The management of the Parson's freehold must be much simpler today. The clergy are salaried (though not handsomely), and the Rector is saved the burden of either renting out agricultural resources or farming them himself. Regular combat with the parishioners not longer takes place !