Ambergris Update.

[Modified from Monograph in Natural Aromatic Materials – Odours and Origins by Tony Burfield (2000) pub. AIA Tampa, USA]

Pre-Amble.

Ambergris has been in the news lately. Bernard Pathé of Cadima Pathé is quoted (Anon 2004) in a trade magazine piece after the finding of a 130Kg piece of ambergris in the atolls of Vanuatu in the Pacific. The article, which carries an actual photograph of the block, reports that pieces of the mass will be macerated for 6 months in alcohol (3g/litre ethanol) “to supply the perfumery demand for ambergris”, said to run at 4 tons/annum. The product is reported to sell at between $500 and $15,000 per Kg, dependent on quality. Petitdidier (1990) had indicated previously that ambergris fetched $4,000 to $10,000 US per Kg in a French cosmetics magazine article. The admission of trading in ambergris is surprising although the article states that the material is not authorised for sale in the USA or Australia. The article also states that Cadima Pathé also trade (totally unethically in my view) in Ethiopian civet paste and castoreum products.

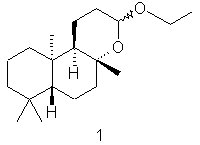

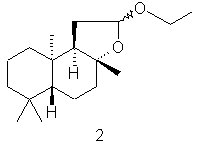

Awano et al. (2005) acknowledge that the use of ambergris is prohibited because of the Washington Treaty, which bans the hunting of musk deer and whales, but describe the distillate of an ambergris tincture made up from a twenty-year old sample of ambergris (100 g in 2 litres alcohol). The authors describe two previously unidentified components as shown below in the tincture (which they describe as ambreine degradation products): 13-ethoxy-8a,13-epoxy-14,15,16-trinorlabdane (fig 1) and 12-ethoxy-8a,12-epoxy-13,14,15,16-tetranorlabdane (fig 2).

In spite of the apparent good fortune of the Cadima Pathé report, ambergris only occurs in approximately 1% of the population of Physeter macrocephalus (the Sperm Whale). Physeter spp., amongst other whale spp. are listed under Appendix I of CITES (CITES 2003). Rice (2002) of the National Maritime Mammal Laboratory, Seattle challenges the widely held belief - that ambergris masses may be found floating in the sea or washed up on the shores and therefore harvesting posing no threat to whale viability. Rice maintains that ambergris is hardly ever industrially sourced from beach finds but is mainly recovered from whale carcasses. To discourage the wholesale slaughter of those few sperm whales still remaining in our oceans to isolate this valuable commodity (it is estimated that there are now only 360,000 sperm whales remaining, compared with a Greenpeace estimate of 1,500,000 in 1978: Petitdidier 1990), trading in ambergris qualities is universally considered an unethical practice by respectable concerns. Except, apparently, in some unenlightened parts of Europe.

Some who trade in ambergris dispute the fact that this activity endangers the sperm whale, and anyway that ambergris cannot be “cultivated” outside of the whale. Looking at the literature however it is apparent that ambergris ‘finds’ have been directly sold to dealers: for example Tennessen & Johnsen (1982) furnish a number of examples – for example that of a Falkland Island whaling station who found a whale with a 304lb lump of ambergris which they sold for Norwegian Kr 400,000.

Description.

Ambergris gets its’ name from the French “ambre gris” (grey amber) to distinguish it from the fossilised resin, brown amber. The raw material results from a pathological condition of the sperm whale Physeter macrocephalus L. syn P. catodon L.

In the normal course of events, calculus (sand and stones) or cachalot, is regularly ejected from the digestive tracts from adult sperm whales. There is some evidence, however, that certain materials, like the indigestible beaks of squid or cuttlefish (Elodone moschata) irritate the whales' digestive system, and in so doing, the offending substances develop a pasty pathological growth. It is possible that the cuttlefish itself contains ambrein, or that ambrein is formed by the digestive processes of the whale’s stomach acting on odourous substances within the cuttlefish. After being vomited out, the floating dark waxy mass is often washed up on beaches where it hardens to a paste as it dries. These deposited ambergris masses can weigh up to 100 Kg, and have frequently appeared in the past floating near, or washed up on the seashores of the African coast, Madagascar, Jaan, Brazil, China, India, the Bahamas and even New Zealand – in 1895 the London market was said to be supplied by whalers from Tasmania and New Zealand (Parry 1925). Fresh material is almost black turning to light gray as it matures. It would appear that in previous times trainee perfumers were taught that the pale or white forms of Ambergris were likely to possess the finest odour, which opinion is also to be found in Poucher's remarkable abbreviated account on ambergris (Poucher 1936) which he wrote in conjunction with a Mr. A.C. Stirling (Poucher & Stirling 1934). In this account, Poucher describes 10 distinct types of ambergris from work done in 1931 with Stirling, graded largely on colour odour and origin: this data can be found repeated on Internet websites dealing in buying & selling pieces of ambergris (unfortunately often without giving due credit to the source).

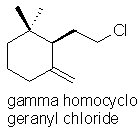

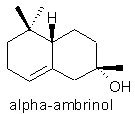

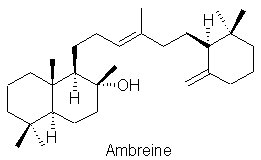

Ambergris contains 46% of cholestanol type sterols (Sell 1990) including (+)-epi-coprosterine and the triterpene alcohol (-)-ambreine (25-45%), which is odorless, but this material is the precursor to other fragrant compounds formed by auto-oxidation, sunlight, and seawater such as (-)-gamma-cyclogeranyl chloride and (-)-gamma-bicyclohomofarnesal. The material is said to be able to retain its odour for centuries, and generally stays as an amorphous mass, with no tendency to crystallise. Mookherjee and Patel (1977) identified nearly 100 volatile substances in ambergris; they described some of the key components and their associated odours as follows:

g-homocyclogeranyl chloride: ozony-seawater (can be towards metallic)

a-ambrinol: moldy-animal-faecal

g-dihydroionone: weak tobacco

g-coronal: sea-water

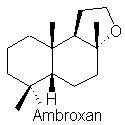

ambroxan: moist, soft, creamy, persistent amber with velvety effect

The odour of a museum sample of grey ambergris examined by the authors team (Burfield 2000) is dry, slightly animalic, musty, earthy, and faintly fishy or seaweed-like in character. It has an exceptional radiance and has a dry, ambery, somewhat marine, long lasting dry-out. Ambergris was traditionally used in tincture form (3% dissolved in 95% alcohol).

Uses.

Ambergris cannot be compared to castoreum or musk, but the physiological properties seem to be similar. Ambergris was traded in N.W. Africa before the 9th Century. Louis XV is said to have used ambergris to flavour his favourite dishes, and Queen Elizabeth I used it to perfume her gloves (le Galliene 1928). Valued as a restorative, & dissolved in wine as an aphrodisiac (Comon 1955, Bovill 1973) and as a perfumery fixative, ambergris is the slowest of all perfume materials to evaporate.

Since the use of animal products in perfumery is no longer considered ethical (the Washington treaty for example bans the hunting of musk deer and whales), ambergris has been replaced by an array of synthetics e.g., Ambroxan (Henkel), and Grisalva (IFF) etc. Ambroxan is synthesized from sclareol, a diterpene alcohol present in Clary Sage (from Salvia sclarea). These synthetic products have a cleaner more intense amber quality, but none of the subtlety and smoothness of the natural material. Ambergris/amber has performed an important role in perfumery for centuries, being used to impart a radiant, intense long lasting, and animalic/ambery quality to both male and female fine fragrances (some authorities, such as Poucher 1936, describe the effect as “velvety”). Ambergris notes are an essential part of more recent male fragrances such as Cool Water, Drakkar Noir and Zino Davidoff. The material was also formerly used for its fixative qualities, and was noted in its ability to bring eau-de-colognes especially “alive”. Synthetic amber chemicals perform an important function in fabric softener fragrances, due to their powerful substantivity.

References.

Anon (2004) “A rare piece of ambergris” Parfumes Cosmétiques Actualités No. 175 Feb/Mar 2004 p28.

Awano K., Ishizanki S., Takazawa O., Kithara T. (2005) “Analysis of Ambergris Tincture” Flav. & Frag. J. 2005; 20, 18-21.

Bovill E.W. (1973) Dragoco Report 1,3.

Burfield T. (2000) Natural Aromatic Materials – Odours & Origins pub. AIA Tampa USA.

Common R. (1955) Indian Perfumer 10, 291, 351.

le Galliene R. (1928) The Romance of Perfume pub. Richard Hudnut New York 1928.

Mookherjee B.D. & Patel R.R. (1977) Paper #137: 7th International Congress on Essential Oils, Kyoto, Japan, Sept 1977.

Parry E.J. (1925) Parry’s Cyclopaedia of Perfumery Vol 1 A-L J & A Churchill p36-43.

Petitdidier J.-P. “Fixeurs Animaux: L’ambre, le castoreum, la civetter, le musc” Parfums, Cosmétiques, Arômes No 90 – Dec 1989/Jan 1990 pp79-82.

Poucher William A. & Stirling A.C. (1934) Chemist & Druggist March 17th 1934, 294.

Poucher William A. (1936) Perfumes, Cosmetics and Soaps 4th edn. Vol 1: Being a Dictionary of raw Materials Together with an Account of the Nomenclature of Synthetics.” Chapman & Hall, London 1 pp 25-34.

Rice D.W. (2002) In: William F. Perrin, Bernard Würsig & J.G.M. Thewissen eds. Encyclopaedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

Sell, C. (1990) “The Chemistry of Ambergris” Chemistry & Industry 20th Sept 1990, Vol 20, pp516-520.

Tennessen J.N. & Johnsen A.O. (1982) The History of Modern Whaling Univ. of California Press Berkeley p322.