Greek vase painting

Top of the pots

The vase painting menu lists many other pages about the techniques and aethetics of Athenian vases. Click here

Search for a favourite vase in the Perseus Index of Vases :

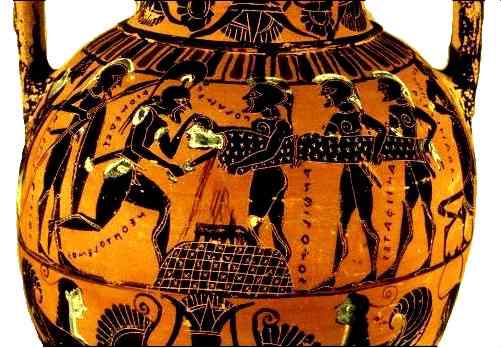

Polyxena by the Timiades Painter

This is London 1887.7-27.2 - a black-figure Athenian amphora probably found in Italy, and dated around 550 BC

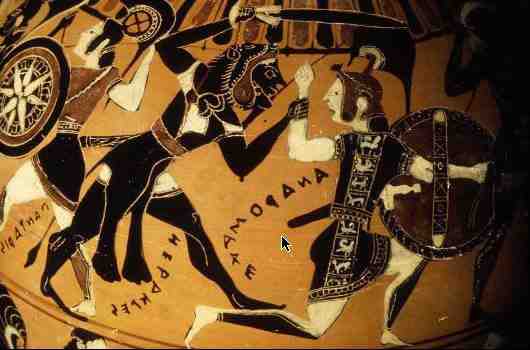

This famous vase is usually attributed to the Timiades Painter - whose other work (Boston 98.916) also shows extreme violence against a woman: Heracles, terrifying with his lion's head actually over his face (like a rubber bondage mask), lunges towards the cowering Andromache, queen of the Amazons, grabbing her right wrist with his left hand, while brandishing a huge sword with his right. Her sword is in her belt, and her shield is useless as she tries to run away.

The London Vase presents an even more horrific image. The context is the end of the Trojan War. Troy has fallen and all the Trojan heroes and many of the Greeks are dead. Before the survivors can return home, the ghost of Achilles demands a sacrifice, mirroring the sacrifice of Iphigeneia which enabled them to get a breeze for Troy ten tears before. Euripides uses the story for his tragedy Hecuba (Hekabe)- where the beautiful youngest daughter of Priam dies so heroically, so modestly and wins such admiration from her Greek murderers. But the Timiades painter has no time for romanticizing. Three warriors hold the girl horizontal - like a battering-ram. They are named as Amphilochos, Antiphates - and, ominously, Ajax, son of Oileus (fresh from his equally unpleasant role in the rape of Cassandra).

From the left comes Neoptolemos, son of Achilles, whose privilege it is to carry out the sacrifice. In a fantastic composite image he is simultaneously running at her (reminding me of an English public school prefect administering a beating) and standing still gripping her by the hair - holding her head up so his sword can penetrate the neck. Polyxena's face is distorted - prefiguring one of the bomb victims in Picasso's Guernica.

A scribbled spurt of blood - for which the artist has used a different colored paint - falls on the altar, from which flames painted with the identical technique rise up to meet it. Another echo is between the fabric covering the tomb with that of Polyxena's peplos - both patterned similarly. She is not quite a sexless tube: although her arms would seem to have been pinioned inside her top, she has breasts round which Amphilochus grasps her firmly and a rather pathetic little bottom. The main actors are all young: the old guard are marginalised: Nestor on the far left, and Phoenix, Achilles' father-figure, turning away from the sickening scene on the far right. The other side of the pot shows young men dancing: now the sacrifice is over they can celebrate. Where does the painter stand? Does he share the physical excitement of the young warriors relishing their duty? Or is there some sympathy for the wretched object that conceals its resemblance to a girl's body?

About 125 years separate this harsh image from Euripides' play, Hecuba (produced around 425 BC). Polyxena is no passive victim now. She is brave and independent, and heroically accepts a death she cannot escape. Talthybius, the herald is describing her death to her mother (translated Vellacott):

"Let me stand free, and kill me; then I shall die free.

Since I am royal, to be called slave among the dead

Would be dishonour." The whole army roared consent;

And Agamemnon told the youths to set her free.

When she heard this, she took hold of her dress,and tore it

From shoulder-knot to waist, and showed her breasts, and all

Her body to the navel, like the loveliest

Of statues. Then she knelt down on one knee and spoke

The most heroic words of all: "Son of Achilles,

Here is my breast, if that is where you wish to strike;

Or if my throat, my neck is ready here; strike home."

He with his sword - torn between pity and resolve -

Cut through the channels of her breath. A spring of blood

Gushed forth; and she, even as she died, took care to fall

Becomingly, hiding what should be hidden from men's view.

Lekythos with woman

Harvard 1959.193 - a red-figure lekythos from Gela in Sicily, dating from around 470 BC and said to be in a style near that of the well-known painter Douris.

A full description, bibliography, and explanation of technical terms is available.

The discussion below is entirely mine!

- A closer view of the woman

- Her top half

- Her bottom half (note the feet!)

- Her head (how realistically does it go with her back?)

- Her alabastron (oil-bottle) At first glance this seems a very dull and ordinary vase - hardly worth a second look. But if, like me, you are obsessed with the notion of concocting an explanation for any vase painting, here is rich material for flights of fancy!

The vase is a lekythos - that is a container for oil. Presumably this wasn't for culinary oil (too small) - and would therefore have been a container for probably perfumed oil, which would have been used for "anointing". But anointing what and when? One explanation is that the lady is about to make an offering at a tomb, which will include oil and maybe ribbons from the box beside her - she is herself holding an oil-bottle in her hand. The scene would be one illustrating dull, boring 'everyday life'. But why should a painter, especially one perhaps associated with the workshop of Douris (famous for his sexy symposium scenes, and Satyrs disporting themselves - as in London E 768, the psykter in the British Museum) choose something so mundane?

Let us suppose that the woman is looking at someone 'offstage'. The artist has apparently tried to show her turning round (at any rate her feet are facing in the opposite direction!). Has she been sent to fetch something? And if so, presumably it is the alabastron which she is extending to her 'visitor'. The presence of an alabastron in a painting (as convincingly argued by Eva Keuls in The Reign of the Phallus) is an indicator of the female's function as sex-object (just as the equally prevalent kalathos [wool-basket] indicates her other function). Is she then a shy, or perhaps reluctant young bride, or, more interestingly, a tease - anticipating Kallonike in the Lysistrata?

The consumers of Athenian vases were - especially in the Archaic period - predominantly men. Men were unlikely to be interested in genre scenes from women's everyday life. This was something in which they had little if any interest. Far more probably this lekythos shows a scene of subtle and ambiguous sexual innuendo. Is she a wife or a hetaira? Who is the man offstage? What's in the box? Is she randy or reluctant? Will she or won't she?

For further exploration of this theme, I would strongly recommend Eva Keuls : especially chapter 9 (The Sex Appeal of Female Toil). Compare also Berlin 2289 by Douris, which shows a most attractive young lady in theory rolling out a skein of wool (roving), but in fact providing a tantalising glimpse of the hidden world of the womens' quarters, as well as an equally exciting glimpse of leg and upper thigh as she rests her leg on a small stool. Significantly, this is on a drinking cup for exclusive male use. For the boxes and containers as symbolic of a woman's privacy - see the essay in Pandora, the catalogue for the current exhibition of painting and sculpture illustrating the woman's world in ancient Greece.