An edited version of this text was published in InfoMusa 13 (1): 43 - 44 (2004). The original text follows:

Musella splendida – a response to Valmayor & Danh

The prospect of a new Musella in Indo-China will cause febrile excitement among Musaceae enthusiasts worldwide. I was excited when I heard of Valmayor and Danh’s paper (2002) but became sceptical as I read and re-read it.

Some of my concerns are trivial, some more serious. On a trivial level, Valmayor and Danh’s characterisation of M. lasiocarpa as "the world’s rarest banana [] until today [] found only in arboreta and botanical gardens" is incorrect. First, monotypic genera are not inherently "rare". Second, the uncritical reproduction of nurserymen’s hyperbole is misplaced. Musella lasiocarpa has been available from specialist nurseries in the UK since 1997. I bought my first plant for the equivalent of about US$ 40 and Fig. 1 shows that plant in my garden in September, 1997. Through micropropagation M. lasiocarpa has been on sale throughout the UK for US $20 or less in a national garden centre chain since 2002. I believe the same to be the case in the US. Further, although its use may not be prohibited by the ICBN, A. J. B. Chevalier (1934) has already used the epithet for Musa splendida, a species he claimed forms immense populations in the Red River delta. Incidentally, the 1994 VASI/INIBAP mission to Vietnam collected in the Red River delta but did not report finding the plant. Musa splendida is ripe for modern reassessment.

My more serious concerns centre on the fact that Valmayor and Danh base their separation of Musella splendida on the briefest of descriptions of M. lasiocarpa, which they tacitly assume covers the entire species in all situations. Valmayor and Danh refer to no living or herbarium specimens of M. lasiocarpa. They ignore the possible influence of edaphic, climatic and biotic factors on the growth of M. lasiocarpa. They ignore the possibility of infraspecific variation in M. lasiocarpa and that their material might fall within this range.

Plant stature

First, it seems to me to be important in a paper that uses in part plant stature to differentiate a new species that the author’s should be precise about how this is measured. The INIBAP banana descriptors specify that height should be measured from the base of the pseudostem to the emerging point of the peduncle. It would be naïve to assume that every author has always adhered or does now adhere to this standard. Valmayor and Danh do not give the basis for their height measurements nor do any of their photographs of the plant contain a scale. Precision in the matter of stature is especially important when dealing with Musella where the leaves are held rather stiffly upright and thus contribute significantly to the overall height of the plant in the vegetative phase. In a vegetative plant of M. lasiocarpa only about 30% of the "height" of the plant is pseudostem, the rest is leaf, see Fig. 1.

Figure 1

Vegetative plant of M. lasiocarpa in the author’s garden at 50 m in the south-west of the UK.

The scale is 1 m long.

Second, in dealing with such a plastic character as stature one surely has to consider the influence of growing conditions. Valmayor and Danh’s knowledge of M. lasiocarpa seems to derive exclusively from C. Y. Wu (1976) who describes a plant "less than 60 cm tall". Valmayor and Danh mention but do not refer specifically to Franchet’s (1889) type description of M. lasiocarpa. This too states that M. lasiocarpa rarely exceeds 60 cm and at face value underpins Wu’s comment. Franchet’s paper includes an illustration of M. lasiocarpa that may possibly be a faithful reproduction of the plant found by the Abbé Delavay in 1885. If so, it looks nothing like any M. lasiocarpa that I have seen growing anywhere. Franchet’s drawing lacks a scale and is so peculiar that it is perhaps risky to draw any conclusions from it. However, the logical interpretation of Franchet’s drawing is that, almost completely lacking a pseudostem, the height of the whole plant, from ground to leaf tip is 60 cm. Baker (1893) agreed with this and stated that the "whole plant [is] 1 - 2 ft. long". If Wu’s height measurement is as I suspect derived from Franchet then the literature does indeed indicate that M. lasiocarpa is a very small banana. But is this generally true of the plant in vivo? A plant of M. lasiocarpa growing "sur les rochers de Loko-chan" at 1,200 m (Franchet 1889) will look different to a plant growing in my garden at 50 m in the south-west of the UK or in "fertile forest soil with abundant moisture" at 118 m in northern Vietnam.

The height from the base of the pseudostem to the emerging point of the peduncle of a male-phase M. lasiocarpa in my glasshouse as I write is 45 cm and the inflorescence is 25 cm on top. In full leaf just before flowering my plant was about 1.3 m overall, i.e. from the base of the pseudostem to the tip of the tallest leaf held at its natural angle. Fig. 1 does not show the same plant but gives an idea of the scale and morphology of a vegetative plant of M. lasiocarpa growing under reasonably favourable conditions in my garden at 50 m in the south-west of the UK. The wooden scale in Fig. 1 is 1 m long and the plant approx. 1.3 m tall overall. M. lasiocarpa can be bigger than this. I supplied two plants of M. lasiocarpa from my stock to Mr Wim Kea of Amstelveen, Holland, and saw them grown to 2.5 m or more in his glasshouse, Fig. 2. I submit that M. lasiocarpa is a much larger plant than Valmayor and Danh suppose.

Figure 2

Two vegetative plants of M. lasiocarpa from the author’s stock growing side-by-side in the glasshouse of Mr. Wim Kea, Amstelveen, Holland. These plants are approximately 2.5 m tall overall. The smaller plants in the background are a commercial crop of Musa (AAA group) ‘Dwarf Cavendish’ grown for ornamental use.

Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 show that the length to width ratio of M. lasiocarpa leaves is > 3, a ratio that Valmayor and Danh associate specifically with M. splendida. Despite Valmayor and Danh’s statement to the contrary their reproduction of Wu’s illustration shows that the length to width ratio of M. lasiocarpa leaves is > 3 and not < 3!

Neither Wu nor Valmayor and Danh comment on Musella’s habit of simultaneously developing more than one leaf-opposed sucker from the same site, frequently subtended by a leaf-base; a suckering habit very different from Musa.

Valmayor and Danh’s lack of precision about the measurement of their plants in relation to M. lasiocarpa, their failure to consider environmental effects or to provide a scale in any photograph of the plant leave me lacking any evidence that M. splendida is significantly larger than M. lasiocarpa.

Inflorescence structure - bract characters

In the female phase, the pointed tips of individual bracts of M. lasiocarpa can indeed be "spread apart precociously, prior to folding down at the base", Fig. 3a, a character by which Valmayor and Danh differentiate M. splendida. But the bract character changes as the inflorescence matures, a process that in M. lasiocarpa takes months. In the male phase, illustrated in Wu 1976 and Fig. 3b and 3c, the bracts of M. lasiocarpa are much smaller, thinner and "markedly imbricated". This change in bract character can be seen in Valmayor and Danh’s own photographs; compare their Fig. 2 with Fig. 3 and Fig. 5 with Fig. 6. I think that female phase bract character in M. lasiocarpa may anyway be rather variable and depend upon whether the plant is in full leaf or leafless at the onset of flowering.

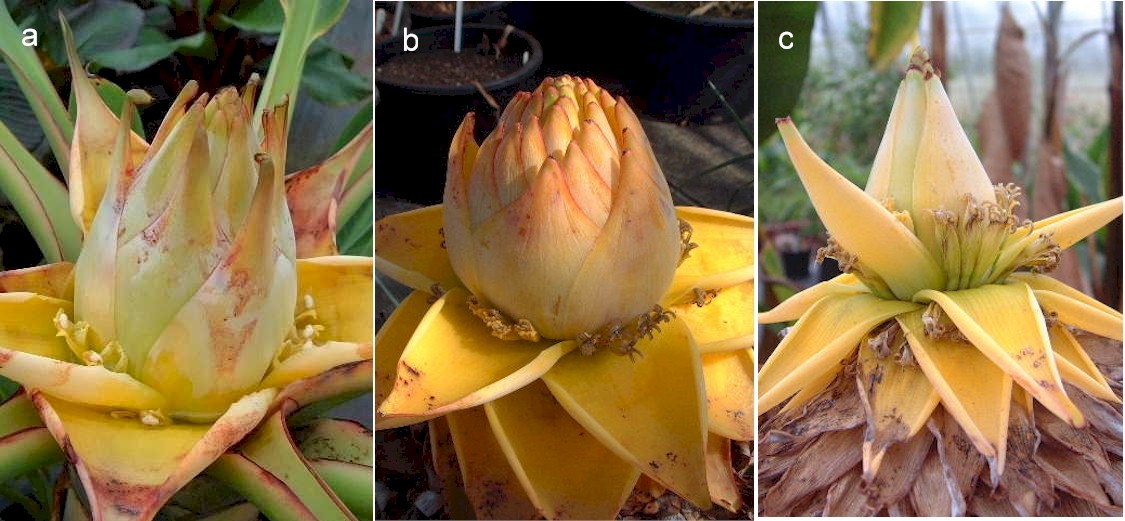

Figure 3

a) Female-phase inflorescence of M. lasiocarpa in the author’s glasshouse in June 2002. b) Male-phase of the same inflorescence in April 2003. c) Late male phase of the same inflorescence in July 2003. Note the change in bract character.

I doubt that the bract characters mentioned by Valmayor and Danh are sufficient to justify the separation of M. lasiocarpa and M. splendida. Incidentally, the flowering of suckers after the main axis is also sometimes seen in M. lasiocarpa. These suckers arise, as Valmayor & Danh’s Fig. 3 shows, from the lower and not the upper leaf bases of the pseudostem.

Valmayor and Danh’s "interesting Musella specimens" in their Fig. 9 are, I submit, merely random photographs of M. lasiocarpa and meaningless in the context used. It is incorrect to suggest that Fig. 9 is evidence of possible further species of Musella. One can quickly find many more photographs of Musella lasiocarpa on the Internet showing yet more variation between plants of the species. This variation is environmental or related to the age of the inflorescence when photographed. The use of micropropagation to produce M. lasiocarpa in Europe and the US tends to limit genetic variation and commercially available seed is notoriously difficult to germinate.

Floral characters & parthenocarpy

It is unconvincing when, without any supporting explanation, the type description of a supposed new banana "species" states it is "seedless and parthenocarpic". One immediately wonders by what mechanism is this "species" disseminated in the "vast forests" of northern Vietnam? I am not sure that the fruit shown in Fig. 8 can properly be described as parthenocarpic anyway. The large air spaces visible in the cross section seem to indicate the fruit is simply undeveloped. I have seen Musella lasiocarpa produce similar fruit when it has not been pollinated.

Valmayor and Danh state that M. splendida has hermaphrodite basal flowers and contrast this with M. lasiocarpa which is said to have female basal flowers. Valmayor and Danh do not properly describe the hermaphrodite flowers of M. splendida and nor does Wu properly describe the female flowers of M. lasiocarpa. "Female flowers are borne at the base of the inflorescence" writes Wu cited by Valmayor & Danh. That is hardly diagnostic. Indeed, the paucity of Wu’s publication on Musella lasiocarpa is one reason why the Royal Horticultural Society (2004) persists in referring to the plant as Musa lasiocarpa, following Simmonds (1960). Incidentally, Simmonds, who obviously did not know the plant at all well, based his inclusion of the plant in Musa on perianth characters not on its being rhizomatic and polycarpic. On my M. lasiocarpa the female flowers have rudimentary filaments and the male flowers rudimentary styles. It is necessary properly to describe the hermaphrodite flowers of M. splendida since Musaceae flowers can be structurally hermaphrodite but functionally hermaphrodite, female, male or even sterile. One might argue that the term should be restricted to flowers that are functionally hermaphrodite, i.e. that can be selfed to produce viable seed as in Musa velutina. If Valmayor and Danh are using the term in this precise sense then what is the explanation for the hermaphrodite flowers of M. splendida not setting seed? Valmayor and Danh make no comment on this or on the presence or viability of any pollen produced by these hermaphrodite flowers.

Conclusion

It is with regret that I conclude that it is premature to claim a new Musella species from Vietnam when populations of Musella in China, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam, and perhaps elsewhere in Indochina, are so inadequately characterised. I have no doubt that there are interesting Musaceae discoveries to be made in Indo-China. Indeed, the plant found by the INIBAP/VASI mission known as VN1-054 is undoubtedly a hitherto undescribed species of Musa (see www.users.globalnet.co.uk/~drc/musaspyunnan.htm). There may well be other species of Musella awaiting discovery but on the evidence they present Valmayor and Danh do not convince me that M. splendida is one of them.

I have M. lasiocarpa from Kunming, Yunnan through the courtesy of Prof. Hu Zhihao and have deposited in vitro shoot cultures of the same with the ITC in Leuven. I will gladly exchange in vivo material with Valmayor and Danh (and, indeed any other interested party) so we can compare material side by side in the same environment. There is botanically interesting variation in Musella lasiocarpa (Versieux 2002) and some may perhaps be horticulturally useful.

David Constantine

drc@globalnet.co.uk

2 High Street

Ashcott

Somerset TA7 9PL

UK

E-mail:

Musaceae website: www.users.globalnet.co.uk/~drcLiterature cited:

Baker, J. G. (1893). A synopsis of the genera and species of Museae. Ann. Bot. 7 : 189 – 229.

Chevalier, A. J. B. (1934). Bananier spontanes de l’Indochine. Rev. Bot. Appliq. 14: 517.

Danh, L. D., Nhi, H. H. and Valmayor, R. V. (1998). Banana collection, characterization and conservation in Vietnam. InfoMusa 7 (1): 10 – 13.

Franchet, A. R. (1889). Un nouveau type de Musa. Musa lasiocarpa. Journ. de Bot. (Morot) 3 (20) : 329 – 331.

Royal Horticultural Society (2004). RHS Plant Finder. Dorling Kindersley. London.

Simmonds, N. W. (1960). Notes on banana taxonomy. Kew Bull. 14 (2): 198 – 212.

Valmayor, R. V. and Danh, L. D. (2002). Classification and characterization of Musella splendida sp. nov. InfoMusa 11 (2): 24 – 27.

Versieux, L. (2002). A Study of Genetic Variation in Musella (Musaceae): an endemic monotypic genus from Southwestern China.

http://www.nmnh.si.edu/rtp/students/2002/virtualposterinfo/poster_2002_versieux.htm

Wu, C. Y. (1976). Musella lasiocarpa. Icon. Corm. Sin. 5 : 580 – 582 (in translation provided by Valmayor & Danh, 2002) .