Issue 9, November 1984 - Speech Synthesisers

| Home | Contents | KwikPik |

The word is that attaching any old speech synthesiser to your Spectrum will allow you to have cosy chats together. Henry Budgett determines whether this is one of the first signs of madness. | ||

|---|---|---|

For years science fiction films and

futuristic novels have depicted an era

when man and machine can communicate in perfect harmony. The reality, of

course, is slightly different. While speech

recognition has yet to be fully developed

(ACT's latest Rascal notwithstanding),

chip-based speech synthesis has been

both mastered and available for several

years. Until recently the computing

power needed to produce human-

sounding utterances was substantial.

Now almost every home computer is

capable of being equipped to talk back to

its owner at a price that won't even break

the average piggy bank. SOUNDING OFFWhen we speak we produce three distinctly different types of sound. The most obvious are the 'voiced' or vowel-type sounds; oo, ar, ee, and so on. These are produced by air from the lungs making the vocal cords vibrate. The frequency of this vibration determines which vowel sound we hear.The second group is the unvoiced or 'fricative' sounds; ss, sh, t and ff. Here the air from the lungs rushes past the vocal cords without making them vibrate and the frequency produced is controlled by the positioning of the lips and tongue. Finally there's silence or, to be more precise, the minute gaps that occur within words (for example six, eight) where we change from voiced to unvoiced and vice versa. FAKING ITIn order to generate speech-like sounds, the electronics designers generally go for one of two methods. The first - and until recently the most common - is synthesis by rule. If the frequencies contained within speech are analysed it's possible to devise a system of rules that allow us to re-create any sound from its basic frequencies.These 'building blocks' of sound are called phonemes and by using them in various combinations any word can be constructed. The individuality of a human speaker tends to be lost when speech is generated like this but the words can be clearly understood. Because the synthesis rules for each |

phoneme are built into the equipment,

the user has simply to supply a list of

phonemes to be spoken. It's then possible to generate complete sentences

instantly, simply by calling up a string of

stored phoneme commands. In reality

these phonemes tend to be called allophones; this is because the various

building blocks sound different depending on their positioning within a word or

phrase. However the principle's much

the same. The second method for generating speech relies on the fact that the human ear and brain are very good at filling in gaps. The speech we hear over a telephone line is (British Telecom permitting) perfectly understandable. Yet technically the quality - the range of frequencies we can hear - is only one- fifth of what we'd expect from a standard hi-fi system. We understand what's being said only because our brain does the job of filling in the gaps. With the fall in cost of computer memory it's now possible to convert speech into digital information compressed many hundreds of times by a wonderful mathematical technique called Linear Predictive Coding. The resulting numbers representing the original speech are stored in a ROM. To get any of the stored words out again as speech is easy; we simply give the computer the address in memory of the word and the digital information is recovered and converted back into sound, and because the original speaker's words have been stored, all the personal characteristics remain. That's why Acorn's speech chips for the BBC Micro really do sound like Kenneth Baker. WHAT'S THE USE?The commercial uses for speech synthesis are so many and varied that it's just about impossible to list them all. Looking just at the tip of the iceberg it can be used to replace taped announcements at railway stations and airports; in America it's widely used on the telephone system to inform callers of mis-dialled numbers and engaged or withdrawn services. Speech synthesis units are also being incorporated into cars like Maestros and Montegos as part of the standard instrumentation so, as well as being something |

of a sales ploy, they can provide warnings

the driver can hear without having to

take their eyes off the road. A major

contribution to road safety perhaps? As far as we are concerned in the home computer and electronic games market, speech synthesis is generally used to enhance games. Scores can be read out and warnings of imminent enemy attack can be given to warn players leaving them free to concentrate on the tactics of the game. Of the five speech units under review here, four of them use the phoneme system and one the stored speech method. Let's take a look at how they succeed in fulfilling their purpose. SUMMARYIf you're looking for a means of adding a voice to your Spectrum and of incorporating the facility either into games or just for fun, then the Currah MicroSpeech is almost certainly going to be the best buy for you. It's also got the largest number of games already written for it if you prefer to use shop-bought software. Another of its clear advantages over the other units is the addition of a BEEP amplifier for putting the sound through the TV.For those of you who haven't yet bought a joystick controller or a sound generator and fancy a speech synthesiser at the same time, then the Fuller Box/ Orator combination - though expensive - offers the lot in one package. Serious users of speech output have an equally clear-cut choice. The superior quality offered by the DCP S-Pack's Digitalker chips make this the logical buy for anyone using the Spectrum as an annunciator rather than as a game machine. The manuals supplied aren't good enough by far, but the Digitalker chips are more versatile than you might think, so if you buy this one get in touch with National Semiconductor for the real data. Of the remaining two units, the Cheetah offers a built-in amplifier and speaker whereas the Timedata unit doesn't; their respective prices reflect this. Neither of them comes close to the overall 'usableness' of the MicroSpeech and they both lack the BEEP amplifier and keyword voicing. |

|

| ||||||||

|

This interesting design puts

the Spectrum sound (including

any speech) through your TV's

loudspeaker - which makes a

lot more sense than many of the

other methods I've seen. To get

the sound out there's one flying

lead from the back of the Micro-

Speech that goes to the EAR

socket and another for the TV

socket. (The new TV socket is

fitted to the back of the unit.)

You do, however, have to

unplug the EAR lead when you

want to LOAD a new program;

perhaps another socket would

have been better. A small 'trimmer' is fitted to allow the TV

signal to be tuned in to produce

the best combination of sound

and picture and once set the

MicroSpeech didn't need any

further adjustment. MicroSpeech uses the allophone system, with the added |

advantage that every keyword

on the Spectrum can be voiced

for you. "Great for the blind", I

thought, but then someone

pointed out that it isn't a Braille

keyboard ... Anyway, you can

turn the keyboard voicing off if

it gets too much for you. SOFTWARE: The Micro- Speech comes with a cassette that on one side offers a rather silly adventure game that speaks to you, and on the other a demo of the various facilities. Written in Basic, the demo is well worth a look if only to see how the 'professionals' construct their words from the allophone set. When you're driving the device from your own programs the allophone strings are built up in a special string variable which is then automatically spoken. It may save a lot of memory to put the words you |

|

|

want into DATA statements as

strings, rather than to store the

actual strings themselves.

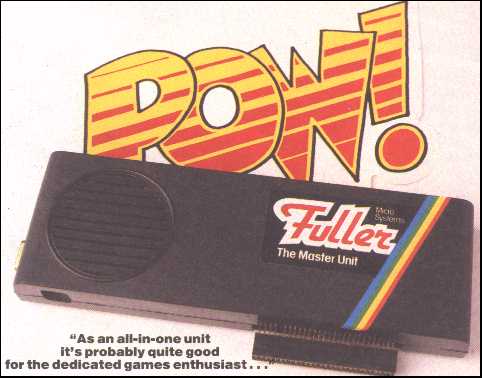

Experimentation here is probably worthwhile if you've got a

lot to say! MANUAL: Neat, clear, well presented and very thorough! Need I say more? SUMMARY: If you want to boost your Spectrum's sound output and fancy the idea of a speech synthesiser, then this has to be worth considering. The only possible complaint about it is the fact that it doesn't have an expansion connector. FULLER BOX/ORATOR Price £56.00 Fuller Micro nn xxxx xxxxxx xxxxxxxxx HARDWARE: Designed as much more than just a speech synthesiser, here is a unit that fits right across the back of the Spectrum and measures 235mm by 100mm by 40mm. Because the casing masks all the |

| |||

|

you very much. If you want

more details on the sound chip

itself, try the official GI Data

Sheet. The manual's explanation of allophones is quite good

but fails to expand into real

example. That's why it's a good

idea to LIST the demo program. SUMMARY: As an all-in-one unit it's probably quite good for the dedicated games enthusiast who likes the idea of tinkering with sounds and speech. As a speech unit in its own right, it's rather big and clumsy and nearly twice the price of its opposition. S-PACK Price £29.95 (Extra Word Packs £12.95 each) DCP Microdevelopments n xxxxxxx xxxxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxxx xxnn nxx HARDWARE: Based on the National Semiconductor 'Digi- talker' system this was the only review device to use compressed speech. In terms of producing intelligible utterances it wins hands down over all the rest but there are several reservations. It comes housed in a 75mm by 110mm by 45mm plastic box and mounts horizontally behind the Spectrum. In its favour is the provision of an expansion bus connector but, unfortunately, the rest of the construction is fairly low-grade. Inside are two PCBs, one providing the bus and the other the speech synthesis components. An internal speaker is provided along with a 3.5mm jack socket to connect the device to a larger external speaker. The volume control is an edgewise potentiometer, in my view a cheap and nasty approach. The speech chips are all socketed and there's provision for |

installing four vocabulary

ROMs ... our review model

had all four fitted. When I first

tested a Digitalker system some

three years ago these were the

standard chips. Although the

price has fallen dramatically

(the experimenter kit was then

about £130 with two vocabulary

ROMs), the repertoire hasn't. It

may be worth contacting

National Semiconductor direct

to see what else it can offer (UK

offices are in Bedford). The speech quality from this unit is excellent. It's easy to hear that the log-on message "This is Digitalker" is spoken by an American female and the rest of the words in the first two ROMs are spoken by an American male. I'm also pretty sure that there are two other people speaking on the second pair of ROMs, which is an indication of the sort of information a digitised speech system contains that you don't get from an allophone system. SOFTWARE: Er, there isn't any! You just OUT the required word number to the appropriate port and the device says it. MANUAL: Not a lot of use, I'm afraid. The four A5 sides tell you how to use the thing, but miss out on all sorts of interesting details. Your best move is to get the National Semiconductor data sheets (usually free) and find out from them how to string words together, get parts of words and a whole lot more besides. SUMMARY: For pure speech that's immediately understandable this wins hand down. On the other hand you may want words that aren't in its vocabulary and, as it stands, there's no way to make them. Therefore, it's main use would be in a dedicated system announcing times and other numeric data - it's not much good for games and so on. | |

|

normal socketry at the rear of

the Spectrum most sockets are

duplicated on the back of the

Fuller Box. I say 'most' because

the TV aerial lead isn't; you've

got to take the box apart to feed

this through. The inside of the box is, to be reasonably polite, a mess! The sound and speech chips are both standard socketed General Instruments devices, but the rest of the construction is a hotch- potch of extra wires and piggy-backed chips. Still, as well as providing sound and speech the fully expanded Fuller Box also provides a BEEP amplifier with volume control, joystick port and an electronically switched LOAD/SAVE system - which means that you don't have to keep on unplugging the EAR lead while saving programs. An extra 3.5mm jack socket has been installed at the back of the unit which isn't explained |

anywhere in the manual, but it

turned out to be an extension

speaker socket. SOFTWARE: Activating the speech chip is just a matter of using the OUT statement to pass the relevant allophone number to the Orator. The chip contains 64 standard allophones, but quite why Fuller suggest you try a loop from one to 255 is a mystery. Included are two demonstration programs; one covering the Box in general, the second dealing with the Orator. Listing the program is likely to provide rather more information than just listening to it! Imagine gets a posthumous plug for its software, some of which works with the Orator, I believe, and all their joystick games are compatible with the joystick system used by the Box. MANUAL: It's the sort of paperwork that looks good at first sight but doesn't really tell | ||

| SPEAKER COMPARISON CHART | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SYNTHESISERS | Currah MicroSpeech | Fuller Box/Orator | DCP S-Pack | Timedata ZXS | Cheetah Sweet Talker |

| FEATURES | |||||

| Synthesis type | Allophone | Allophone | Compressed speech | Allophone | Allophone |

| Allophone coding | String | Numbers | Numbers | String / Numbers | Numbers |

| Keyword voicing | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Internal amplifier | Uses TV | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Internal speaker | Uses TV | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| BEEP amplifier | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Volume control | Uses TV | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Demonstration tape | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Software provided | In ROM | No | No | On tape | No |

| Games available | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| PHYSICAL NOTES | |||||

| Size (in mm) | 75 by 75 by 28 | 235 by 100 by 48 | 75 by 110 by 45 | 65 by 78 by 40 | 110 by 75 by 50 |

| Format | Horizontal | Horizontal | Horizontal | Upright | Upright |

| Case material | Plastic | Plastic | Plastic | Plastic | Plastic |

| Expansion bus | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Home | Contents | KwikPik |