|

CHAPTER 13. MODERN DEVELOPMENT. |

In the short space of about 30 years, starting from the end of the First World War, Cranham was transformed from a rural parish of agriculture into a dormitory suburb of London. Clearly this is not the first time that London has impinged on the history of the parish. We have seen that our agricultural lands have always been valuable due to the nearby metropolis as a guaranteed market, and we have also seen that Cranham Hall (see Chapter 2) was precisely the sort of estate that was attractive to 18th century London merchants. The ease with which he could get between Cranham and London was also attractive to Oglethorpe (see Chapter 11), who perhaps may be regarded as Cranham's first commuter ! Nonetheless, twentieth century development has seen perhaps the biggest discontinuity in Cranham's history. It is a story of developing communications, housing, and the rising middle class.

Traditionally, a letter had to be taken to Romford, Brentwood or Grays by private messenger, where it would then join more general, but still private, postal services operated by stage coach owners. Letters were bought and sold as they changed hands, and the mark-up at each stage was the incentive for these private carriers; the highest price for a letter was paid by its recipient (141).

In the early 19th century, the mails were organised a little better for London. Although Cranham was still beyond the range of the London two-penny post (235), a postmaster in the service of the London General Post Office (GPO) was established at Romford in the 1820's. A regular mail coach ran westwards from Romford to the City, and on reaching Stratford, was in district no.18 of the GPO. The GPO mail carriers wore armbands with Royal Coats of Arms, and carried the mail in distinctive wicker baskets (236).

White's directory notes in 1848 that a daily delivery and collection of mail at Cranham itself had begun. Letters could be pre-paid with a postage stamp, invented 8 years before, and were taken to a sorting office at Romford for further dispatch by rail or road. By 1886, there was a post-box in the wall of the Rectory, which was cleared at 5 p.m. each day except Sunday (5). This post-box was probably similar to the working Victorian survivor in the wall at the junction of the Ockendon Road and Pea Lane. The volume of the mails must have increased steadily because, by 1908, the Rectory's post-box was cleared three times a day, and there were at least two other boxes elsewhere in the parish (101).

Cranham gained its own sub-post office in 1925, in a pre-fabricated hut on the location of the current day 'Cranham Garage'. In 1945, the sub-post office moved northwards, to a small shop in Front Lane near the present site of the Social Centre. Today there are two sub-post offices; one is at the junction of Front and Moor Lanes, and the other is at the eastern end of Avon Road, again near its junction with Front Lane. The north of the parish is served by a third sub-post office, although this is just over the border, in the parish of Great Warley.

In spite of the fact that Cranham is cut by no fewer than three railways, Cranham has never had a railway station: rail passengers have always had to travel first by road to South Ockendon, Upminster or Romford. This is also in spite of the fact that, today, the population of Cranham is bigger than that of Upminster.

The railway was promoted jointly by the Eastern Counties Railway (ECR) and the London and Blackwall Railway (LBR). The London, Tilbury and Southend Railway (LT&SR) was authorised by Act of Parliament in 1852. The LT&SR line opened in 1854, initially from the City to Barking, and then to Tilbury via Dagenham Dock. It left the ECR’s Colchester line just east of Forest Gate station and travelled via Barking, Rainham and Purfleet to Tilbury. The main aim of the promoters was to get access to the ferry service across the Thames to Gravesend. The line was opened to the public on 13 April 1854 and the trains used the Bishopsgate station of the ECR and the Fenchurch Street station of the LBR. The trains travelled in two parts and were united at Stratford station for the onward journey to Tilbury. Since the majority of passengers used Fenchurch Street rather than Bishopsgate, as from 1 November 1856 the Bishopsgate portion of the trains was removed and all LTSR trains used Fenchurch Street.

The line was extended from Tilbury to Southend in the following stages (150):

Tilbury - Stanford-le-Hope 14 August 1854

Stanford-le-Hope - Leigh 1 July 1855

Leigh - Southend 1 March 1856

Four perfin postage stamps from the LT&SR are known between 1889 and 1910 (228).

In order to relieve congestion at Stratford on the ECR, a line was built from Gas Factory Junction on the LBR to Barking via Bromley, Plaistow and East Ham and this was opened on 31 March 1858. From that date all LTSR trains used this new line. The ECR continued to run ‘locals’ to Barking however.

An extension of the railway to Shoeburyness was opened on 2 February 1884. The Act of Parliament which authorised this also authorised the construction of a ‘cut-off’ line from Barking via Upminster and Laindon to Pitsea, which was completed a year later. The LTSR directors expected that this line would relieve congestion caused by the opening of Tilbury Dock in 1886. In fact the traffic generated by the dock was very disappointing and congestion of the old main line from Tilbury was never a problem until the 1900’s. Only in 1903 did the rail-borne traffic from the new dock exceed 200,00 tons, which the railway considered the ‘minimum’ amount needed to justify working it. Most traffic was forwarded by river in barges or lighters rather than by rail. The day trippers for Southend, from the East End of London, could now avoid the slow goods trains to the docks. Often the day trippers travelled in District Railway specials, which ran to Southend, via the London tunnels, from as far away as Richmond and Wimbledon (203). As Benton and Parish (273) have pointed out, this relieving cut was seminal for the modern development of Upminster. The ‘cut-off’ line shortened the distance to Southend by 6 miles and was opened in stages as follows:

Barking - Upminster 1 May 1885

Upminster - Horndon 1 May 1886

Horndon - Pitsea 1 June 1888

The new line did, however, have some secondary advantages to the LTSR. It prevented the Great Eastern Railway developing lines in the area, it opened up more land for possible development and it shortened the journey time to Southend. Once the line was opened, most through services to Southend used it.

The land for the line through Cranham was bought from the Cranham Hall estate (151). The line deliberately skirted the Glebe, passing just to its North. This was probably because of the difficulty in establishing a freehold for sale, out of the church property.

"Tilbury Tanks" were massive, thunderous, black machines which shook the ground and pulled red coaches, from the point of view of the small boy in the Brickfields. One of them was called "Cranham" (no.73 on the LT&SR, built at the North British Locomotive Works in 1903). Like many others, "Cranham" was an 0-6-2T, used for both passenger and freight duties; she was identical to the "Corringham" (202). The Midland Railway absorbed the LT&SR in 1932, and "Cranham" was renumbered no.2184. In 1946, the London, Midland and South Railway took over, and "Cranham" then became no.2224. Cranham went to the scrapyard in 1949 (202).

The line from Upminster to West Horndon, was not electrified until 1959. The original wooden sleepers survived even longer, eventually being replaced by concrete ones at the Cranham Brickfields on the Down line in 1966, and the Up line in 1968.

Cranham's second railway originally ran from Romford to Grays, crossing the main line at Upminster. It was authorised in a Act passed on 20 August 1883. It has to be said that this line was promoted with the principal aim of preventing the Great Eastern Railway gaining access to Tilbury Docks (although it did also provide access to the important market town of Romford). By proposing this line the LTSR blocked access to Tilbury to the GER, but the resulting Parliamentary battles and other trade-off’s gave the GER the right to build an independent line to Southend via Rayleigh. The LTSR was more or less forced to build this (largely un-profitable) branch line and had the problem, in future years, of having the GER as a competitor for its Southend traffic.

The Upminster - West Thurrock section line was not fully opened until 1 July 1892, the section from Upminster to Romford was not opened until 7 June 1893. The delay in completing the line was not due to any engineering difficulties, but due to the reluctance of the LTSR to complete it ! No doubt they felt it was an unnecessary line, but built it anyway in the expectation that it would be justified by increases in traffic from the Tilbury dock and as a preventative measure against GER encroachment.

|

Middle distance diagram for 1913 showing the Cranham and Ockendon sidings. |

|

Middle distance diagram for 1913 showing Upminster station and the tramway to the brickworks |

The Upminster - West Thurrock section was single line, apart from 18 chains at the West Thurrock end and 13 chains at the Upminster end. The Upminster - Romford line was single throughout, although the Midland Distance Diagram for 1913 (of which there is an excerpt above) shows the line as double.

The original LTS&R station at Romford had two platforms, and a passing loop for the steam engines; the passing loop survived into the 1970's. The Great Eastern Railway was always a separate company, and there was a separate entrance for the LTS&R Upminster branch on the opposite side of South Street; the remnants of this arrangement can be seen today at street level, and although there is now a single entrance at Romford, passengers still must cross the bridge to get to the Upminster branch. Before renovation, the LT&SR station, with its cast iron pillars and intact waiting rooms were attractive, if they could be seen through the dirt, and the original flight of stairs from the LTS&R platform down to street level was still visible. There is now a typical, ugly, anonymous brick shelter at the end of our branch line at Romford, courtesy of British Rail, Network South-East, who can justify only half a platform for the reversible electric trains.

With the District Line electrification and extension to Upminster in 1932 (see below), the Romford-Grays branch was divided into two at Upminster. Wantz Bridge then carried trains between Upminster and Grays.

The branch was originally worked by the "Ockendon Flyer", an ancient 0-6-0 saddle tank engine. Once again, although apparently locally beloved, a photograph of her has not survived. The engine operated, after 1932, only between Upminster and Grays on the "one engine in steam" principle, forward and reverse, although passing loops were available at Upminster, Ockendon and Grays. It is reported that the first and last trains on summer days were often rather slow because the driver set his rabbit traps in the morning and collected his dinner from the embankments en route in the evening!

Miraculously, both parts of this branch have survived in spite of efforts (most famously by Beeching) to close England's branch railways. Upminster to Grays was electrified in 1960, although a daily, diesel-drawn freight train was worked Up each morning in the early 1960's. A token system is now needed for the (typically) two reversible trains on the branch today. Survival of the branch through Cranham during the Beeching era was probably due to the strategic importance of the line: with bombing still in clear memory, the branch offers a second access to Britain's rail network, in the event of obstruction of the line between Tilbury, an important port, and Barking via Dagenham Dock. It has recently received a new lease of life with the opening of the 'Chafford Hundreds' station to serve the Lakeside shopping centre, with some through trains from London now travelling to Southend via Ockendon.

Both of the LTS&R lines through Cranham, to Ockendon and West Horndon, have several crossings. There are five railway bridges in the parish. The four bridges of the Grays branch are contemporary with the building of the railway itself, and are i) Wantz Bridge, ii) an unnamed rail-above bridge to its South, and iii) two road-above bridges in Pike Lane and the Ockendon road. Wantz Bridge has long been a local accident black-spot, claiming lives, even before modern volumes of road traffic, as early as 1932 (61). In 1959, the north bridge abutment was shifted back a few feet, and the entrance to Front Lane adjusted about 25 yards eastwards. The Ratepayers campaigned for mirrors often (see Chapter 12), and a mini-roundabout is the modern solution.

The fifth railway bridge in Cranham is road-above at Front Lane. (Photographs are available of the bridge, both north and south views.) The date of this bridge is unknown, but its width suggests that it is rather later than the railway itself. Whether it was preceded by a narrower bridge or by a level crossing has not been discovered. The bridge at West Horndon does contain brick available in the 1880s, so perhaps a narrower, earlier bridge is more likely. The new, road-above bridge for the M25 to the east of Frank's Wood has been made ingeniously to also provide for the Moor Lane to Warley Street footpath; it is near the old manor house of Warley Franks, and is just outside Cranham's eastern boundary.

There are several foot crossings across both LTS&R lines in Cranham, for those who walk the public footpaths. The most frequently used a re the one from The Brickfields to the "Thatched House", and the tunnels connecting Deyncourt Gardens to the "Mason's Arms". This latter path runs precisely along the boundary with Upminster.

Cranham's third railway came with The London Transport Underground railway depot, built between 1930 and 1932. The land that it occupies had previously been Guyler's Farm. There is no record of any local resistance to its construction.

There can be few parishes with as many railway lines and yet no station. The Parish Council petitioned the railway companies for a station on three separate occasions in the 1930's, but were always rejected (61). In 1946 a piece of land was purchased at Wantz Corner for a station, but nothing came of the plan; Judith Anne Court now occupies the site. A station by the present electrical sub-station at the Front Lane bridge, or an Underground station would be much more use, although car parking at the centre of the parish would doubtless then become the next problem.

In addition to the LTS&R and London Underground, three minor railways have also existed in the parish. In about 1900, a spur was built from the eastern edge of Frank's Wood serving a siding to the brick works, a little to the north (149); the spur ceased operations in 1920. This spur, 1 mile and 22 chains from Upminster station, had its own 'Cranham Sidings' signal box at TQ581(5)873(8) and a trailing connection with the down (Southend bound) line. It served the "Shenfield and Cranham Brick company" works. Jeffrey R. Kelsey, from boyhood memories in the 1960s, was able to describe the location of this signal box precisely (personal communication with the author), although the only photograph that appears to have survived of it is from 1925 (203). (The location is also confirmed by the Middle Distance diagram of 1913).

Secondly, a tramway ran from the North East corner of Upminster goods yard, along the western edge of Cranham for about half a mile, to another the Upminster Brick Company works in the north of the parish, in the nineteenth century. There does not appear to be been a physical connection between the goods sidings and the tramway. Its only visible trace now is a shallow cutting in the back gardens of houses in Eversleigh Gardens and Claremont Road (TQ567(3)870(0) to TQ568(0)872(0)). The Midland railway map (or ‘Distance Diagram’ in Midland parlance) states that there was a siding for the ‘Upminster Brick Coy’ at the station, but does not indicate exactly where it was.

Thirdly, on the line to Ockendon, there was the ‘North Ockendon Agricultural Siding’siding, sited 1m 51 chains from Upminster and just outside the parish boundary. There does not appear to have been a signal box here, so we can assume that access to the siding was controlled by a ground frame, which was unlocked by a key attached to the Upminster - Ockendon section train staff.

The cost and standards of service of rail travel are sources of considerable dissatisfaction to today's parishioners. British Rail appears to be going through that part of its cycle where the rail system is supposed to be locally-oriented. At the present, the mainline running through Cranham is known nationally as "London's misery line". Indeed, a remarkable volte face is that British Rail is now advertising on billboards in their stations for day trips to the steam-preservation, private railways in the south-east. The re-privatisation of tracks and services is now also contemplated. People have an intrinsic attraction to railways in general, and to steam engines in particular. Perhaps the hitherto suffocating bureaucracy is finally learning how to capitalise on this attraction, within the confines of sound economics.

For those interested, there is further information on the rest of the LT&S lines available.

Cranham very nearly got a fourth railway but it was never built. It was a communication between the Thames Haven and Dock Railway Company line (which was built between Mucking and Thames Haven) and Romford, that just clipped the southwest corner of th eparish, including Spring Wood. Plans for this went back as far the 1836 Act of Parliament authorising its construction but these were formally abandoned in 1853. Both Edward Ind of Cranham and James Esdaile of Upminster were part of the initial Board and Wasey Sterry was the line's agent at Romford.

|

Peter Kay has plotted the line of the planned extension to the TH&D railway on this section of the Ordnance Survey map of 1843-4 (with Upminster to Ockenden railways added.) |

Many thanks to Andrew Frith for his contribution to this section. Much of the material is from "The London Tilbury and Southend Railway - A History of the Company and Line", written and published by Peter Kay, Orchard House, Orchard Gardens, Teignmouth, South Devon, TQ14 8DP.

The post was conveyed by a daily omnibus running between Ockendon and Romford, via Cranham and Upminster, as early as 1848 (see above, ref. no. 18). In 1928, a regular, motor-driven service began between Upminster Station and the Cranham post office, via St.Mary's Lane and Wantz Corner. This 'bus was run by the London General Omnibus Company Ltd., and used a single deck, solid-tyred vehicle; the route was numbered G.1. In 1928, the fare to Upminster was 1d. (149). The late E.G.Ballard remembered that a driver at this time was called Ernie Brazier, and that he was a son of the publican at the Hacton "White Hart" (266).

In 1938, the route was renumbered 248, and the old single deck 'bus was replaced by a fleet of three new double deckers. These new 'buses had pneumatic tyres, and three forward and one reverse gears. These 'buses had to be of a special design in order to get under Wantz bridge; this bridge provides only 13 feet 2 inches clearance, and the height of a standard London double-decker 'bus is about 14 feet (most bridges allow at least 14 feet 6 inches headroom). The design of this special type of 'bus included, upstairs, bench seats in rows of four with little headroom, and a sunken walkway channel along the right-hand side. The walkway created a lowered ceiling for those sitting on the right hand side of the 'bus downstairs. The potential for bruised heads was therefore not restricted to the upper deck !

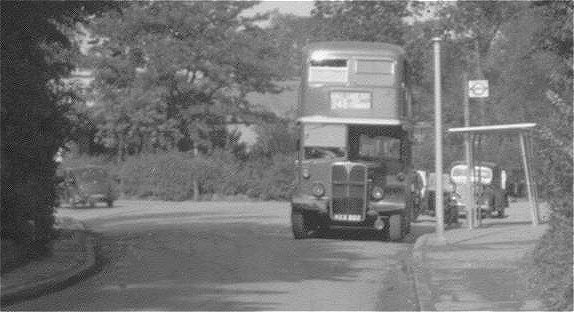

|

A 248 bus waiting to set off for Upminster. Its crew were probably drinking tea in the gatehouse to the London Transport Underground train depot just behind the trees at the extreme left of the photograph. Taken in 1956, Courtesey I. Radford |

The old 248 'buses were the scene of much drama. Mothers sprinting up the Front Lane bridge, shouting and waving behind the 'bus, could usually be explained by their intrepid pre-school children having escaped their attention, climbing aboard, and heading for Upminster on their own. The author (at the age of three) was on board with his mother one day in the summer of 1959 when a driver was stung by a bee in his eye; the 'bus mounted the pavement and came to a halt just before ploughing through the railings at the pond in Front Lane (this resulted in being given some chocolate by a lady from one of the nearby houses, and was one of the best things that happened that week !). Competition for the front, upstairs seats was intense amongst the children on the 'bus, although the stamping on the floor probably did not amuse the driver, whose ears were just a few inches below. Riding the 'bus as it turned round at the Moor Lane / Front Lane junction was a sport; many were the times that we ran away from an irate conductor, but it did save the crossing of a busy road, and was a useful safety tip for unaccompanied children.

In 1953 route 248 was extended from Upminster station, northwards along Hall Lane, and then part of the way down Avon Road. This provided 'bus service to the new estate ("Cranham Park"). In 1959, route 193 (Rainham to Cranham, via Roneo Corner, White Hart Hornchurch, Upminster Station and Avon Road) was added. This terminated in the heart of the new development of Cranham, at Brunswick Gardens. On Sundays, route 193 did not operate, and route 86, originating as far away as Bow, came all the way down Avon Road.

In 1970, the special, but by now ancient, double-deckers were replaced by single-crew, single deck 'buses. An automatic ticket machine (which rarely worked) helped the driver collect fares. Route 248 then began at Upminster station, passed through Cranham via Wantz Bridge, looped round Brunswick Gardens, headed west via Avon Road, and then visited Upminster Station for a second time, en route for Romford via the "White Hart" at Hornchurch. Commuters, home-bound to the centre of Cranham, were now seen standing outside Upminster station, anxiously scanning left and right to see whether the first 'bus would go up Hall Lane or down to St.Mary's Lane; a quick sprint was then needed !

A few attempts have been made to connect Cranham to Brentwood and Harold Wood by 'bus. The Eastern National Co. has tried twice, but failed through insufficient usage. The most recent attempt is London Transport's route 246, following the route of 248 from Cranham as far as North Street, Hornchurch, but then heading north for Harold Wood.

There has been 'bus service to the East, by an Eastern National service, for a long time. These routes cross the parish on St.Mary's Lane between Romford, West Horndon and Basildon. The route numbers have included 15, 15A, 16, and 16A. Only those parishioners living near the "Jobber's Rest" public house and Frank's Cottages have made much use of these services: they are not really designed for Cranham, but rather to provide access to Romford from some of the more remote places to the east.

A recent innovation is the Hoppa. This minibus may be hailed along Moor Lane without a 'bus stop. But nothing is new, and this was the practice on route G.1 in 1928. It now costs 30p to ride to Upminster, some 72 times the cost in 1928.

There have always been numerous springs and wells in the parish. The pond in Front Lane, just north of Wantz Corner, is one example; note that it is filled to a height well above that of the road level at the bridge. A water main from Romford was laid to the parish in 1912.

The electricity main did not arrive in the parish until 1933 (61). Before this, the parish lit some streets with gas lamps, but the date of the gas main has not been discovered (but it must be, therefore, before 1933). Prior to these amenities, solid fuel stoves, paraffin heaters and lamps, and oil would have been the principal sources of energy.

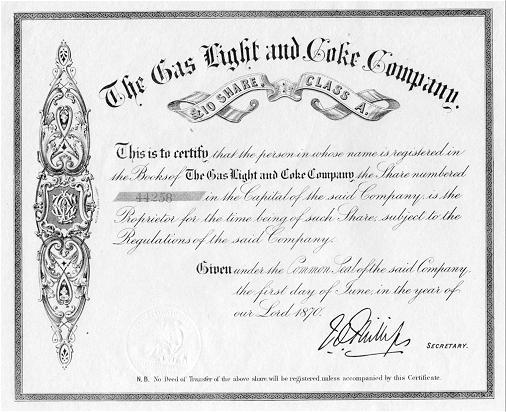

Below is a share certificate from The Gas, Light and Coke Company. This certificate, dated 1870, is rather earlier than when this company first brought the gas main to Cranham. This company eventually evolved into North Thames Gas which in turn became part of British Gas PLC.

The roads of the parish began as rights of way, of mud, and bounded by parallel rows of hedges between the fields. Two examples of these "green lanes" may still be seen, one south of All Saints', on the footpath to the Ockendon Road, and the other (more overgrown), south of the Brick Fields, on the footpath to the "Thatched House" public house (TQ572(2)854(0) to 572(2)851(6), and TQ579(5)871(0) to 579(5)872(0), respectively). Figures 35 and 36 show the roads in the parish in 1809, some remaining today as footpaths, whilst others are gone completely (153).

Maintenance of the roads has long been realised as being of great importance. In 1285, the manors were charged with keeping the King's Highway by the Statutes of Winchester. The Highways Act of 1555 shifted the burden from the manors to the parishes; all residents were required to spend a number of days each year working on the roads or they could pay for a substitute.

The 1555 Act also required that each parish appoint a Surveyor of the Highways. The Surveyor was authorised to dig for stones and other useful road materials anywhere in the parish, and he also organised the labourers. The Surveyor's job was popular with landowners, because in this way they could control the damage, if any, that would be done to their own lands whilst exercising their authority; Oglethorpe, amongst others, was a Surveyor of the Highways for this reason.

In the eighteenth century an Act of Parliament was required to establish a turnpike. A turnpike authority was responsible for a the maintenance of a road and charged tolls to all except the Royal Mail, for its maintenance. There were no turnpikes in Cranham, and the Turnpikes were eventually abolished in the United Kingdom, although they survive, in an highly sophisticated form, in New York, Massachusetts, and elsewhere in the United States.

The Highway Act of 1835 abolished compulsory annual road labour for the parishioners. Instead, the parish was empowered to impose a rate for road maintenance. At Cranham, the ratepayers were the landowners, largely the same group that controlled the vestry. There was little motivation for this group, therefore, to tax themselves for the roads, instead of using the parish labourers for free. The muddy tracks described above, in an era when MacAdam and others knew very well how to make good roads, was the result at Cranham.

In 1888, under new law, some roads were categorised as main roads and became the responsibility of the County, thus justifying a County rate. In 1894, minor roads were made the responsibility of the new Parish Councils; this responsibility has descended, with the changes in local government described in the last chapter, to The London Borough of Havering today.

The Southend Arterial Road bisects the parish. It was built as a four-lane highway, with parallel bicycle tracks in 1925 (see map). There is no evidence that the local community objected to its construction. During World War II, it was used as a linear depot, from Gallows Corner to Southend. Vehicles were queued for the 25 miles or so, prior to the invasion of Europe, and the troops camped on the grass verges. This linear depot used one side of the dual carriageway, and the other was used as a service road (154).

|

A view north up Front Lane from about 200 yards north of St Mary's Lane in 1956. The road name plate for Pond Walk can clearly be seen on the right. Photo I. Radford. |

The M25 runs northwards along the eastern edge of the parish, before cutting through the narrow northern part of Cranham quite substantially. This is no geographical accident. The road was built between 1979 and 1983, although the first news of its plans was presented at a public meeting at the Hall Mead School in 1970. There was considerable resistance from those who lived at Cranham. In the south of the parish the original plan was to have this road adjacent to the eastern edge of Frank's Wood. There was considerable acrimony at the public meeting, for fear of noise, and the danger of the road so close to the playing fields. It was felt that if this road was needed at all, then it should follow the line of the A128 in Warley. Miss Lesley Lovelock was an especially prominent opponent of the road at this time (155, 156).

Eventually a compromise was reached. The road crosses the parish between the A127 and the site of Beredens, but south of this, the line was otherwise moved ¾ mile to the east; agricultural land now separates the M25 from Frank's Wood. Even so, the noise when an easterly wind is blowing is quite noticeable throughout the parish. Those who live at Frank's Cottages have borne the brunt of the adverse effects of this road. However, it should be said that it is important for the country as a whole that London should have a good orbital road, and that the range of reasonable lines for the road would all have affected Frank's Cottages. The road has interrupted Front Lane, north of its meeting Moor Lane, and now only a footbridge connects the northern part of Cranham to the rest of the parish; Coombe Lodge, and the north of the parish are now well and truly separated from their historic connexions. The M25 / A127 interchange lies just outside of the parish. The volume of traffic proves the necessity of this motorway.

|

Junction of M25 with A127 showing decimation of Codham Hall Wood. Note Folkes Farm in top left hand corner |

Whilst it is not modern development, we might as well discuss all aspects of Cranham's roads in one place. More or less every parish has its rumours of Roman Roads. In the case of Cranham, the rumours emanate from respected and famous commentators (157, 158, 159, 160). The subject is some what contentious. The evidence is presented here as objectively as possible, for the reader to reach his or her own conclusion, although the author must admit to scepticism.

In 1899, Dr.Miller Christy was engaged in a general study of Roman roads in Essex. Dr.Christy noted that the authentic piece of Roman road to the sea-fort at Bradwell came to an abrupt end, apparently after running for only about a mile inland. The intended destination of this road was (and is) unclear. Christy proposed that it was headed in a long arc through Latchingdon, Wickford, along the present-day B187 through Cranham via Wantz Bridge, to Upminster and Hornchurch, and then along the present day line of the A124 to Ilford, where it would meet the present day A12, another authentic Roman road. The details of this line was justified by aligning various road junctions and topographic features. This masterpiece of hypothesis was not tested by field walking, and appears to have been devised from the 1" Ordnance Survey map.

In 1922, Dr.J.H.Round made it his business to take many of Christy's hypotheses apart, including the supposed Ilford to Bradwell Roman road. The cornerstone of the attack was that the present day A124 could be shown to be a mediaeval road, developed in conjunction with the building of the palace at Havering. Furthermore, unless there is some geographical obstacle, Roman roads are usually direct, and often straight: the latitude of Othona is 12 miles north of London, and yet Christy's route ran south-east from Ilford.

Christy replied to the attack in 1926 (157). He conceded that he was wrong about the section between Ilford and Hornchurch. However, he maintained that at Hornchurch the Roman road must then have taken a more southerly route to London, through Barking, entering the city at Aldgate after joining the present day A13 (another authentic Roman road). As far as Cranham is concerned, this modification to the hypothesis makes no difference. In support of this new route, Christy pointed to i) a Roman ford about ½ mile south of Bow Bridge, ii) a concentration of Roman artefacts along this line, including some sarcophagi at the British Museum, and iii) the known popularity of roadside burials amongst the Romano-British.

Christy also showed one new concept in his defence. Roman development usually proceeded, ribbon-like, along their roads. The typical development plan was known as "reticulation", in that short roads were arranged perpendicular to the principal route. Within these developments, back streets were again usually arranged perpendicularly, so that in fully developed examples an incomplete grid of streets and squares of building and agricultural development existed either side of the main road. Christy pointed out that Cranham is a member of a band of parishes which are all long and thin and oriented perpendicularly to his proposed Roman road (see Chapter 1). These parishes are aligned roughly north and south and stand next to each other in a band that stretches from Dagenham to Downham, including Hornchurch, Upminster, Cranham, Great Warley, and Childerditch. There is another famous example of this arrangement, a band of long, thin parishes straddles the Icknield Way near Wantage, in Berkshire (237). If the shape of these parishes represent Roman land claims, then they could be good evidence for a road passing through them.

At Cranham it can be added that the pattern of public footpaths and roads in the south of the parish are also arranged along the lines of a partial grid of squares and rectangles (figure 35); it is difficult to think of another explanation of the pattern of these rights of way, especially because the field shapes are very irregular today. Reticulation suggests cultivation, and this pattern of roads is in the most fertile part of the parish, with the best water supply. The roads are not reticular in the north of the parish, suggesting a later colonisation of less attractive land (figure 36). Nonetheless, there is no other independent or archaeological evidence for Roman colonisation in the south of the parish, and no place-names surviving from pre-Saxon times. The evidence is still circumstantial as far as Cranham is concerned.

Christy's amended hypothesis has not been challenged in print since 1926; nor has it been supported. The concept of reticulation still has support, although some believe this pattern to be evidence for occupation even earlier than Roman times (272, 274, 275). In Essex, the clay makes survival of physical evidence less likely than in other counties. There is also little local stone: the beautiful typical stone roads, twelve feet wide and two feet thick (161), are unlikely to have been built by Romans here. Persons digging around one of the many left and right jogs of the B187 would probably have the best chance of finding archaeological evidence. Nothing was found during the M25 construction. And there, for the present, the issue rests.

Cranham has evolved from a purely agricultural village into a parish that, in terms of land area, is now about one quarter dormitory suburb. The north, south and east of the parish is still mainly farmland.

The one exception to this generalisation was the Cranham Brick and Tile Company Ltd. This company established clay digging and brick kilns in 1900, on the present day site of Brickfields, just west of Frank's wood and north of the railway. The company had a private spur and a signal box (see above).

This company had a chequered history. On June 17, 1904, H.M. Factories Inspector W.C.C.Hoar prosecuted the company for the employment of three boys overtime. The company was fined a pound, with 7/=d costs, probably an insignificant amount. In 1908, the company merged to form the Shenfield and Cranham Brick and Tile Co., Ltd. In 1908, seventy men were employed at the brickworks, compared to a total population for the parish of about 390; many of the workmen must have come from outside Cranham (101).

The brick-earth began to run out in 1915, and the site was finally closed in 1920. The buildings on the site were not demolished until 1929 (149). It was proposed to build a landscaped parkland there in 1934, but nothing happened and then the War intervened. The site was eventually bull-dozed flat in 1946 (149). It is now used as parkland, with two meadows regularly mown by the Council, and some robust playing equipment in the upper one. There is still a lot of rough land, Frank's wood, and a pond which is fed by an underground spring. Two formerly agricultural fields between Heron Way and the Brickfields proper were added in 1949, but are undeveloped. Kerry Close cut into the upper addition in 1965.

Some of the bricks can still be found in garden walls in Argyle Gardens, Upminster.

Domestic housing "in these material years" (226), is always a matter of personal taste and preference. Only the objective history of housing in Cranham will be dealt with here.

It is not easy to trace the evolution of domestic houses in Cranham. We can assume that the simple daub and wattle, timber frame cottages were the norm even a hundred years ago. The unique survivor (a seventeenth century example, but with a modern roof) has just been demolished in Front Lane. The only thatched building in the parish is at its extreme north-east edge, near Coombe Lodge; it is a modern house. Apart from the predecessor of the present Cranham Hall (Figure 8), the first documented brick building in the parish was the workhouse of 1828.

In 1844, there were 42 cottages in the parish. Eight were near Coombe Green, six on Back Lane (now Moor Lane), eighteen on Front Lane, seven on St.Mary's Lane (some being the workhouse conversion), two on The Chase, none on Pike Lane, and one south of the church (238).

In 1925, there was at least one terrace of four houses, known as "The Pantiles" in Moor Lane. They are still standing with their eponymous roofs (45).

There was a plan as early as 1925 for an extensive, planned suburb, north of the railway, and between Hall Lane in Upminster and Moor Lane. It was intended as a middle class, garden suburb of mostly detached houses. A few examples were actually built, for example that at the western end of King's Gardens, and another in The Crescent. The project failed, although it was widely advertised.

During the 1930's, there are several entries in the Council minutes stating the need for more housing at Cranham. The first council houses were opened by Cllr. Mrs. A. W. Williams, J.P., a county councillor, on October 16, 1931. They were named the Oglethorpe Cottages, and stand today on the south side of Moor Lane. These houses were not provided with bathrooms until 1974, and many have now been sold to private ownership.

Benyon's estate was broken up and sold in 1937 (see Chapter 2). This led to the modern development of the parish. The roads bearing the names of species of birds now occupy one lot, whilst the streets named after dioceses occupy another. Council housing occupies a third lot, where most of the streets' names refer to places and events associated with the colonisation of Georgia (Brunswick Gardens, Waycross Avenue, etc.).