Grapefruit Oil Supply Situation & Grapefruit Juice Contraindications.

Copyright © Tony Burfield May 2005.

Expressed grapefruit oil is produced from the rinds of the large fruits from cultivated grapefruit trees (Citrus paradisi Macfad.), and is basically a by-product of grapefruit juice concentrate manufacture. Distilled Grapefruit oil made by distilling the juice or pulp, is an even more minor oil, with little to recommend it organoleptically, being a mere shadow of the expressed product. Three broad types of grapefruit oils - white, and some pink and red - are all normally available commercially, as well as the relative newcomer: ‘sweetie’ grapefruit oil, developed by the Grapefruit Marketing Board in Israel. This latter fruit has been described as a cross between shaddock (grapefruit) & pumello (Citrus grandis), and the oil has been gaining favour in the last few years amongst the producers of citrus flavourings, not the least because it has been offered at 10% of the cost of Florida white grapefruit oil (Burfield 2005). The annual global production of all grapefruit oil of all types up to 2004 has been variously described at between 30 tons and 200 tons (!); but the principle use for the oil remains for the flavouring of citrus beverages. Fivefold grapefruit oil is also produced which has a lower limonene content, better keeping qualities and improved solubility in many food vehicles compared with the normal oil. The use of the bitter flavouring grapefruit extract material naringen is now contra-indicated in the diets of many people on a variety of medications (see below).

Grapefruit oils are pretty useful in perfumery and natural perfumery - but with the exception of sweetie oil, they are ten to fifteen times the price of orange oil sweet, and additionally have limited availability in commercial quantities, and so they tend to be used more in ‘high end’ perfumery. Uses include application in citrus cocktail fragrances where it blends well with other citrus notes, and in the citrus top notes of male fragrances. Grapefruit oil also blends well with spearmint and herbal notes, and interesting accords can be constructed between grapefruit oil and vetiver oil, and between grapefruit oil and olibanum absolute. The phototoxicity of grapefruit oil limits its use in perfumes to 4% for products not washed off the skin (IFRA Dec 1995; Opdyke 1974). Uses of grapefruit oil in aromatherapy are perhaps more recent, possibly reflecting an increasing global consumption of grapefruit juice sales. Shen et al. (2005) indicate that in rats, sniffing grapefruit oil affects the autonomic nerve, enhances lipolysis through a histaminergic response, and reduces appetite and body weight.

Supply situation

At a trade presentation meeting of the British Society of Perfumers (May 2005) one leading aroma company showed a synthetic grapefruit aroma compound to delegates on the basis that “grapefruit oil supplies would face another two difficult years”. The background to this has been (a) the price and availability of grapefruit oils and to a lesser extent (b) toxicity worries with grapefruit products - see below.

Israel didn't produce any oil in 2004 at all, diverting all its fruit to juice production – this upset some oil trade buyers who had been using Israeli grapefruit oil pink as a reasonable flavour alternative to Florida white. Due to hurricane activity in 2004, Florida grapefruits ended up rotting on the ground, as we know. In normal times Florida produces around 4 tons of oil around 40% of which is from Marsh seedless varieties, with the parent Duncan variety accounting for less than 10%. California is also a significant producer of the oil. Cuban grapefruit oil availability was also affected as it was caught in the same storms path as Florida. Small quantities of Grapefruit oil have also been available from Mediterranean countries including Italy, Argentina and Brazil, South Africa, and from Australia, but some oil products bandied around the market in 2004 were apparently constructed from limonene, bitter orange oil fractions and synthetic nootkatone, and have never seen a grapefruit! Some grapefruit oil is also produced in the Greek and Turkish parts of Cyprus, but annual volumes produced are quite low. Big hopes have been placed on a successful the 2005 crop, but early indications of forward prices look high. So aromatherapists should be aware that old grapefruit oil stock and synthetic reconstructions have been sold to those aromatherapy oil suppliers with less discriminatory ability to spot these items just lately.

Composition of the Oil.

A good description of grapefruit varieties can be found at: http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/morton/grapefruit.html; however the description of the peel oil composition is somewhat curious, and so an alternative account is set out below.

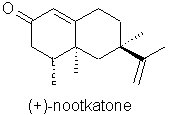

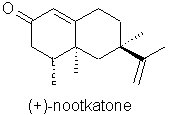

An 1975 ISO standard exists for Grapefruit oil (ISO 3053) and is used for quality assessment. However the more important parameters in commercial trading of grapefruit oils are the organoleptic properties (odour & taste), appearance and (especially) the nootkatone content. Nootkatone is a sesquiterpene ketone which occurs to some extent in all citrus peel oils, the content increasing with the successive ripening of the grapefruit fruits. Since synthetic nootkatone qualities (racemic and dextro etc.) are commercially available via the oxidation of valencene - a sesquiterpene hydrocarbon which occurs in orange oil - care is needed when buying grapefruit oils. The (+)-nootkatone levels which traders might like to see in normal grapefruit oils range from 0.5 to 1.5%, with a minimum acceptability level at 0.3-0.4%, but due to market shortages in 2004, oils with nootkatone levels as low as 0.1 to 0.2% have been traded, reflecting poor oil quality and/or adulteration with distilled grapefruit oil, limonene or other citrus terpene by-products. The nootkatone level of Florida white grapefruit oil normally is higher than pink and red grapefruit varieties, and the non-volatile evaporative residue is lower. Grapefruit oil Florida contains from 85-96% limonene (average 90%) with smaller amounts of aliphatic straight chain aldehydes including heptenal, octanal (to 0.8%), nonanal, decanal (to 0.5%) and dodecanal. Alcohols are represented by octanol (to 0.3%) and linalool (to 0.5%). Esters especially octyl and decyl acetate are also present (to 0.3%), and non-volatile compounds are present from 3 -7.5%.

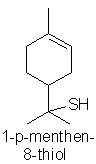

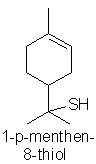

Apart from nootkatone, the character compounds of grapefruit aroma are said to be p-menth-1-en-8-thiol, ethyl butyrate, (Z)-3-hexenal, 1-hepten-3-one, 4-mercapto-4-methyl-2-pentanone & wine lactone [Buettner & Schierberle (1999)] and for grapefruit aqueous aroma cis-and trans-linalol oxides, terpinen-4-ol and a-terpineol [Fleisher & Fleisher (1996)]. It is interesting to note that the odour threshold for p-menth-1-en-8-thiol is a staggering 10-5 parts per billion, and many of us have speculated if the psychophysiological effects of compounds such as these, with such a profound recognition ability by the human olfactory system, are not actually more important than the major constituents of grapefruit oil which aromatherapy teaching relies on. Both grapefruit mercaptan (p-menth-1-en-8-thiol) and thiocineole, another powerful sulphur compound occurring in grapefruit oil, are available commercially (e.g. from Frutarome). The sesquiterpene components of grapefruit essence (not the oil!) were studied by Demole & Engisst (1983) who revealed the presence of powerful odourants such as (+)-8,9-didehydronootkatone.

According to Ziegler (2000) sweetie grapefruit oil has compositional similarities between white and pink grapefruit oil but with increased levels of sabinene, octanol, neral and geranial, with a very low level of nootkatone (0.08% typical in Cyprus grapefruit oil: Burfield 2005). In addition, Sweetie grapefruit oil posses the sesquiterpene germacrenes B & C, in addition to those found in normal grapefruit oil (germacrenes A & D).

Bergaptens in grapefruit oil occur up to 1.5% and include 7-geranoxycoumarin, osthol, limettin, bergaten, bergamottin, bergaptol, which, as mentioned above, has prompted IFRA to advise restrictions on the amount of grapefruit oil to be used in perfumed products not washed off the skin.

Grapefruit juice and oil: drug interactions.

[These remarks are largely taken from e-mail replies and web-based comments over 2004-5 from aromatherapist practitioners asking about the safety of grapefruit oil in relation to drug interactions].

Adverse drug interactions from drinking grapefruit juice have been

known since 1989 or earlier, and are widely reported (see for example

http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hpfb-dgpsa/tpd-dpt/adrv10n1_e.html) but maybe we

don’t yet know enough about the mechanism of enzyme inhibition systems which

seem to be causing the problem. An estimate made in 2004 said that it make take

5-10 years yet to fully comprehend this phenomena, although pro-pharmaceutical

industry sources and websites have attempted to downplay its’ significance. A

popular view seems to be that specific flavonoids present in grapefruit juice (naringen

and possibly narirutin) are slowing down the normal detoxification processes in

the liver (the cytochrome P450 system) increasing bioavailability and slowing

down drug clearance. An inhibition effect on the gut wall cytochrome P-450 3A4

(CYP3A4) isoenzymes and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) also affects bioavailability, the

net effect being to produce elevated circulatory levels of the imbibed drugs in

the bloodstream if taken after drinking grapefruit juice, which in some

situations could be construed as a life-threatening, or perhaps cause damage to

the liver etc. These effects relate to a number of classes of drugs, from those

taken for blood pressure (anti-hypertensive) to lipid-lowering agents to anti-immunosupressive

agents to anti-histamines to AIDS medications, to warfarin.

We don’t know with absolute certainty to what extent other grapefruit

products (grapefruit oil, grapefruit essence oil, deterpenated grapefruit oils

etc. present in some citrus beverage products) are in the same category of

contra-indication as grapefruit juice. If we speculate that the effect is solely

confined to the action of grapefruit flavonoids - then these substances should

not be present in appreciable quantities in mechanically pressed grapefruit

oils, and there should be either no risk, or a much reduced risk. We are told

that orange juice (no variety stated) has been said to have little, or no

effect. But genuine grapefruit oils (if you can find any at the moment) will

also contain up to 1.5% of furanocoumarins, and it seems to be the case that

grapefruit furanocoumarins (such as bergamottin) will also show these inhibitory

effects described above (see

https://secure.pharmacytimes.com/lessons/200303-02.asp). You'll also find

several articles on PubMed confirming this - although the real culprit causing

this problem may turn out to be a biflavanoid derivative of bergamottin.

Alternatively the P450 enzyme systems 2B6 and 3A5 may generate further

inhibitory metabolites from furanocoumarin substrates such as bergamottin.

Lian-Qing Guo et al. (2000) had earlier found all

six furanocouarins present in eight sources of grapefruit juice affected

microsomal CYP3A activity, identifying two new ones in juice and oil, and also

extended the range of possible activity to two varieties of sweetie, three

pummelos and one sour orange (but not sweet orange). Guo et al.

(2000) have carried out further work indicting that furanocoumarins from other

species (e,g. Umbelliferae) are also CYP3A inhibitors.

You can find an SCCP opinion on bergamottin at

http://europa.eu.int/comm/health/ph_risk/committees/sccp/documents/out239_en.pdf

- which indicates that cold-pressed bergamot oil contains 2.2% of the material

(other sources say up to 5%) and cold pressed lime oil contains up to 2.5%.

Reconstituted grapefruit oils currently circulating the small essential oil and aromatherapy supplier markets have even lower likelihood of containing detectable amounts of flavonoids and might not even contain furanocoumarins (if concocted from orange terpenes and nootkatone etc.).

The best advice would appear to be that until we have a crystal clear picture on how grapefruit oil constituents, or their metabolised or biotransfomative processes might produce substances which cause individual drug reactions, then its best to avoid imbibing grapefruit products altogether if taking contra-indicated medications. Inhalation and skin absorption of grapefruit oil via massage would appear to constitute a lower risk, but since alternatives to grapefruit oil readily exist it might be eminently sensible to avoid AT treatments with these items for those on contra-indicated drug treatments for the meanwhile.

This is not the first bunch of adverse reactions from citrus products that we have had just lately - synephrine from the green unripe peels of Citrus aurantium (Bitter Orange) together with other adrenergic amines are known to present ephedrine-like effects (see http://www.itmonline.org/arts/syneph.htm for a discussion). Synephrine is especially present in bitter orange extract at 3-6%, frequently used in flavourings, and just lately, in natural perfumery. Occurrence in other varieties of orange peel such as the Seville orange is also known, but synephrine is said to occur to a greater or lesser extent in most citrus products. My view is that the effects of synephrine could be considered 'adverse' if the subject receiving the material (say in the form of a prescribed Chinese medicinal product for the purposes of weight loss) is unaware that the drug could cause uncomfortable physiological effects – which appears to have been the case in a limited number of reported instances. Here we could take a view that the Informed Consent process between practitioner and client has actually broken down.

References.

Burfield (2005) from the forthcoming second edition of Natural Aromatic Masterials – Odours & Origins (in preparation).

Buettner & Schierberle (1999) Buettner A. & Schieberle P. (1999) “Characterisation of the most odour-active volatiles in fresh hand-squeezed juice of grapefruit (Citrus paradisi MacFayden)”. J. Agric. Food Chem. 47, 5189-5193.

Demole E. & Engisst P. (1983) “Further investigation of grapefruit juice flavour components (Citrus paradisi Macfayden). Valencene- and eudesmane sesquiterpene ketones. Helv. Chim. Acta 66, 138.

Fleisher A & Fleisher Z. (1996) “Aqueous Essence Oils Recovered form a Citrus Aqueous Aroma by the Poroplast Extraction technique” Paper given to Citrus International Symposium Jan 29-Feb 1 1996, Orlando, Florida.

Guo L-Q., Taniguchi M., Xiao Y-Q., Baba K., Ohta T. & Yamazoe Y. (2000) “Inhibitory effect of natural furanocoumarins on human microsomal cytochrome P450 3A activity.” Jpn J Pharmacol 82, 122-129

Guo L-Q., Fukuda K., Ohta T. & Yamazoe Y. (2000) “Role of Furanocoumarin Derivatives on Grapefruit Juice-Mediated Inhibition of Human CYP3A Activity” Drug Metabolism & Disposition 28(7), 766-771.

IFRA Guidelines (Dec 1995) Phototoxic Ingredients: Use Limited.

Opdyke D.L.J. (1974) FCT 12, 723.

Shen J., Niijima A., Tanida M., Horii Y., Maeda K., & Nagai K. (2005) “Olfactory stimulation with the scent of grapefruit oil affects autonomic nerves, lipolysis and appetite in rats” Neurosc. Lett. 380(3), 289-294.

Ziegler H. (2000) “The analysis of Murcott (honey) tangerine and the hybrid Oroblanco (known as Sweetie)” 2nd Citrus Symposium, Lake Buena Vista Florida Feb 15-18, 2000.