CHAPTER 2:

LATER SOURCES

THE easy availability of the chronicle of Martin Polonus in the late Middle Ages caused it to have a lasting influence on Pope Joan's history. At first, other authors were content to copy almost word for word from the account which had by then appeared in many editions of the Chronicon. Such was the case with the Norfolk copy of the Flores Historiarum, and also with another English work: the well-known Polychronicon by Ranulph Higden. Higden was a monk of the Benedictine Abbey of St Werburgh in Chester, where he probably held the position of librarian. He completed the first edition of his comprehensive history of the world in 1327, then added to it over the years until 1352, after which it was extended by monks of Worcester and Westminster up to the end of the century. Higden's own manuscript copy still exists in the Huntington Library in California.

He died around 1363, and a little over twenty years later, in 1387, the original Latin text of the Polychronicon was translated into English by John de Trevisa, a Cornishman, who was the vicar of Berkeley in Gloucestershire. This version illustrates just how closely Higden followed Martin Polonus:

After pope Leo Johan Englysshe was pope two yere and fyue monethes. It is sayd that Johan Englysshe was a woman and was in yougthe ladde with her lemman [sweetheart] in mannes clothynge to Athene and lerned there dyuerse scyences. So that there after she came too Rome and had ther grete men too scolers and redde ther thre yere thenne she was chosen by fauoure of al men. And her lemman broughte her with chylde. But for she knewe not her tyme whan she sholde haue chylde as she wente from Saynte Peters too the chyrche of saynt Johan Lateran she beganne to trauaylle of chylde and hadde a chylde bytwene Collosen and Saynt Clementes.(1)

Not all writers were quite so satisfied with the original story as Higden, and inevitably, as the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries passed, additions and modifications were made to it. The woman pontiff had at first been totally anonymous, then she had progressively acquired a title - 'John Anglicus' - and, in some quarters at least, a papal number. The one thing she did not have by the start of the fourteenth century was a personal female name, but the temptation to rectify this serious omission soon proved too great for the medieval historians to resist. Their natural choice should logically have been 'Joan' or 'Joanna' as the feminization of 'Joannes' or 'John', yet it is surprisingly difficult to trace this name for her prior to the 1600s when it began to be widely used by Protestant polemicists. Certainly the interpolations in the early chronicles of Marianus Scotus and Gotfrid of Viterbo, which we have already discussed, call the female pope 'Joanna', but there is no evidence that these insertions were made much before the end of the fifteenth century. In the case of Gotfrid, his note about Joan was unknown even as late as the 1560s when the English Catholic, Thomas Harding, commented:

...they that in their writings recite an exact row and order of popes, as Ademarus and Annonius of Paris, Regino, Hermannus Schafnaburgensis, Otho Frisingensis, Abbas Urspergensis, Leo bishop of Hostia, Johannes of Cremona, and Godfridus Viterbiensis, of which some wrote three hundred, some four hundred years past, all these make no mention at all of this woman pope Joan.(2)

Harding was arguing with John Jewel, the Bishop of Salisbury, and by this time they were both able to use the name 'Joan' freely and without question, but they were among the first to do so.

Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-75) included a chapter on the female pontiff in his book about famous women in history, De Claris Mulieribus, which was written n the middle of the fourteenth century. One modern translation heads the section with the title 'Pope Joan', but this is misleading as the Latin reads De Ioanne Anglica Papa or 'Concerning Pope John Anglicus'.(3) Nor is the word 'Joan' mentioned in the original narrative, despite its inclusion in the translation. Nonetheless Boccaccio does seem to have been the earliest author to suggest some sort of female name for the woman pope. 'There are some,' he states, 'who say that it was Giliberta,' but he does not adopt the appellation in the main part of his own account, preferring to stay on safer ground with 'John'.

If he did indeed get 'Giliberta' from other sources, as he implies, then they were probably not written ones for there is no trace of them now. There cannot have been any widespread support for the name as few people apart from Boccaccio mention it, though 'Gylberta' is not entirely unknown in Protestant polemic from the early 1500s.

Within fifty years of Boccaccio a much more popular alternative had put in an appearance. Adam of Usk's Chronicon, completed in 1404, was published with a translation just over a hundred years ago, and according to the English version it refers to a 'pope Joan'. A quick check of the Latin text, however, reveals that the correct reading is 'pope Agnes', a name which at one time was quite widely accepted. It was the choice of John Hus who spoke of 'Pope John, a woman of England called Agnes' several times during the Council of Constance in 1414.(4)

On the other hand, a curious manuscript from the Benedictine Abbey at Tegernsee in Bavaria, which was compiled later in the fifteenth century, not only dissociates the female pope from Germany by insisting that she was born in Thessaly, but also calls her `Glancia'.(5) We have encountered this nowhere else. Rather more familiar is the 'Jutta' in Dietrich Schernberg's play, Ein Schön Spiel von Frau Jutten, of around 1490. Despite the German contraction, this must count as one of the very earliest definite references to 'Joan'.

Clearly there was no consensus of opinion on the personal name of the woman pope for more than 200 years after her initial appearance. Not until later did 'Joan' become so universally accepted that today few people are aware of the existence of any alternatives. It is even generally believed that the female pontiff chose the title 'Pope John' because her given name was 'Joan', which is very much a case of putting the cart before the horse.

In the fifteenth century her anonymous lover and friend, now sometimes raised to the status of cardinal, was also honoured with an identity, being called 'Pircius' in the Tegernsee manuscript and 'Clericus' in Schernberg's play. Neither was widely taken up, however, and to most writers he remained a mere cipher. In one or two cases he was even denied the role of father to Pope Joan's child, although the old idea perhaps hinted at in the Chronica Minor, that the baby was the spawn of the Devil, did not reappear. Instead the distinction of fatherhood went to a suddenly introduced 'chaplain' or a 'certain deacon, her secretary'. No doubt this was the result of a misunderstanding of the word familiaris, used in Martin Polonus' Chronicon at this point. Martin intended it to mean a companion, referring back to Joan's earlier lover, but it could be taken to indicate a member of a household, and hence a papal chaplain or secretary.

There was disagreement too about the woman pope's downfall and death. Martin had implicitly suggested that she died or was killed at once when her secret became public knowledge, but others argued in favour of a gentler end. Boccaccio, for example, after describing how her mentor, the Devil, had tempted Joan into the sin of lust, adds that she was taken away from the place where she gave birth, by the cardinals and imprisoned. The 'wretched little woman' was then left to lament her condition until her death some time later.(6)

Kinder still was the anonymous Benedictine monk (on textual evidence possibly named Thomas) of Malmesbury Abbey in Wiltshire, who wrote the Eulogium Historiarum in about 1366. His female pope, whom he calls 'John VII' and places in the year 858, attains the papacy in the traditional way, although the Eulogium is somewhat insulting about her talents, saying that 'so many were fools in the city that no one could compare to her in learning...' The monk then continues:

When she had reigned for two years and a bit, she became pregnant by her old lover, and while walking in procession gave birth, and thus her sin was revealed and she was deposed.(7)

There is no mention at all of her eventual demise, which was obviously not considered relevant.

If Joan did not die at the place where she gave birth, then it follows that she may not have been buried there either. This was certainly the opinion of the copyist who inserted a late and unique interpolation into a Berlin manuscript of Martin Polonus' chronicle. He also took advantage of the singular lack of interest shown by the early writers in what became of the papal child after its traumatic introduction to the world. They had presumably taken it for granted that the baby had died at birth or shortly afterwards, but the copyist devised a different theory. His version explains that, as a result of the female pope's public revelation:

She was deposed for her incontinence, and taking up the religious habit, lived in penitence for such a long time that she saw her son made Bishop of Hostia [Ostia near Rome]. When, in her final days, she perceived her death approaching, she instructed that her burial should be in that place where she had given birth, which nevertheless her son would not permit. Having removed her body to Hostia, he buried her with honour in the Cathedral. On account of which, God has worked many miracles right up to the present day.(8)

How different this is from the familiar account of Martin Polonus. Not only is Joan left to repent her sins in a nunnery, but her son survives his unusual beginnings to rise to the rank of bishop! Furthermore, the figure of the woman pope starts to take on some very saintly characteristics, and miracles even occur in her name. Unfortunately no other sources confirm these odd assertions, which were interpolated into the single Chronicon manuscript some time after 1400. The Cathedral at Ostia never claimed to possess Joan's body, and the writings of Leo, Bishop of Ostia at the end of the eleventh century and the beginning of the twelfth, say nothing about her.

The statement that her child was a son (filius) is also based on evidence which is far from firm. Most of the early authors who mention the female pope and her pregnancy do not actually refer to the offspring itself, but those who do, describe it with the word puer. Although this can sometimes indicate a male child, it was more often used to convey a child of unspecified sex. Only in the fifteenth century did the infant's masculinity begin to be assumed with some degree of unanimity; Adam of Usk in 1404 may have been the first to prefer filius to puer or infans.

An even greater accolade than burial in an important cathedral was given to Pope Joan by a c.1375 edition of the Mirabilia Urbis Romae, a popular guidebook to Rome for pilgrims who wanted some information on the 'sights' as they travelled around the city. These pilgrims were the natural predecessors of the modern tourist, and numerous versions of the Mirabilia were produced for their benefit throughout the late Middle Ages. The 1375 manuscript alone states that the woman pontiff's body was buried 'among the virtuous' in the Basilica of St Peter's itself.(9) Such an honour was unquestionably conferred upon the remains of most ninth century popes, but the Mirabilia's compiler was surely presumptuous in his belief that the bones of Joan were among them.

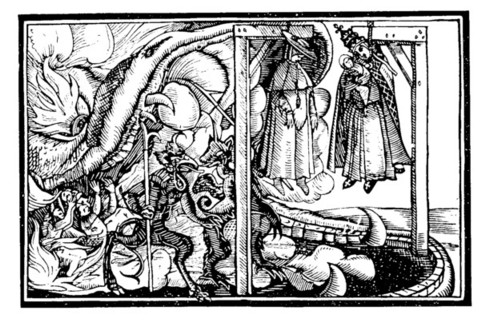

For some later writers, the female pope's death was not the end of her story. They took a considerable interest in the ultimate whereabouts of her soul, and not everyone agreed with the Carmelite Baptista Mantuanus when he resolutely consigned her to Hell in his work of about 1490. According to a woodcut illustration [see below], she hangs there on a gibbet, clutching her child. What the poor baby had done to merit such punishment is not explained, but no doubt it was sufficient that he died unbaptized. Her lover is not forgotten either, for he hangs nearby, wearing the robes of a cardinal.(10)

In contrast to this harsh treatment, an idea grew up at the end of the fifteenth century that perhaps Joan had redeemed herself by deliberately choosing public humiliation. Thus Felix Haemerlein's De Nobilitate et Rusticitate Dialogus, written around 1490, states:

...while in procession from St Peter's Basilica to the Lateran, in the street which leads from the Colisseum to St Clement's Church, she gave birth as she had chosen to do for the remission of her sins.(11)

The theme was enlarged upon by Stephan Blanck in an edition of the Mirabilia Urbis Romae which he compiled in about 1500 during the reign of the Borgia pope, Alexander VI:

...we then proceed to a certain small chapel between the Colisseum and St Clements; this derelict church is situated at the place where the woman who became Pope died. She was heavy with child, and was questioned by an angel of God whether she would prefer to perish for ever, or to face the world openly. But, not wanting to be lost for eternity, she chose the embarrassment of public reproach.(12)

Presumably by this decision she was thought to have saved her soul: an attractive and altogether satisfactory conclusion to her strange story.

Stephan Blanck, Boccaccio, and in particular the unknown interpolator of the variant Martin Polonus text, seem to have felt little in the way of horror or revulsion at the concept of a woman ascending the papal throne. On the contrary, they reveal a growing respect and affection for her which is illustrated by the belief of a few authors, that she was buried honourably in a cathedral or even in St Peter's Basilica. Perhaps this is a reflection of the feelings towards Pope Joan which were current among the general population at the time. Her thirst for power and occasional lapses into immorality were, after all, relatively innocuous compared with the misdeeds of many other early medieval pontiffs.

Boccaccio's fellow humanist Franceso Petrarch (1304-74), however, had no particular sympathy for Joan as a person; nor did the details of her rule and unfortunate death interest him in the slightest. His Chronica de le Vite de Pontefici et Imperadori Romani dismisses her reign in few words, simply saying that after her election, 'she was revealed (as a woman)'. He does not even bother to explain how such a disaster came about and in what manner it affected Joan's subsequent life and afterlife.

For Petrarch instead, the fascination lay in the marvels which he claimed had occurred on the earth following the pope's exposure. These he describes in truly apocalyptic language:

...in Brescia it rained blood for three days and nights. In France there appeared marvellous locusts which had six wings and very powerful teeth. They flew miraculously through the air, and all drowned in the British Sea. The golden bodies were rejected by the waves of the sea and corrupted the air, so that a great many people died.(13)

The imagery here is taken straight from the Book of Revelation, and clearly Petrarch intended to draw a direct parallel between the consequences of the female pope's unlawful pontificate and the seven plagues of Revelation, which were released upon the opening of the Seventh Seal. The first of these was a rain of 'hail and fire mingled with blood' (Rev. 8:7), and the fifth was of locusts with 'the teeth of lions' (Rev. 9: 3-11). The drowning of Petrarch's insects also echoes the casting into the Red Sea of the locusts which formed the eighth plague of Egypt (Exodus 10:19).

But such flights of fancy were only part of the picture, for some of the other additions made to the basic account of Pope Joan's tragic life, during the 250 years after its initial appearance, had a distinct ring of truth. In the first chapter, we encountered an inscribed stone which, according to the earliest writers, marked the position of her death and burial. This was very quickly forgotten, but over a century later certain other memorials began to be associated with the story in its place. The 1375 edition of the Mirabilia guidebook introduces two new details into the tale:

Nigh unto the Colosseum, in the open place, lieth an image which is called the Woman Pope with her child... Moreover in the same open place is a Majesty of the Lord, that spake to her as she passed, and said, 'In comfort shalt thou not pass' and when she passed she was taken with pains, and cast forth the child from her womb. Wherefore the Pope to this day shall not pass by that way.(14)

The 'Majesty of the Lord' - which was presumably some kind of figure of Christ in Glory - was not linked with Joan by any other author, but the more intriguing statue of 'the Woman Pope with her child' crops up with increasing frequency from the beginning of the fifteenth century onwards.

The Welshman, Adam of Usk, travelled to Rome in 1402 and stayed there for several years. His Chronicon, compiled between 1377 and 1404, was intended as a continuation of Ranulph Higden's great chronology. It includes an account of the coronation of Pope Innocent VII in 1404, which Adam may not actually have witnessed himself, although he must at least have seen part of the preliminary procession. The final stages of the Pope's solemn progress to the Lateran are described thus:

After turning aside out of abhorrence of pope Agnes, whose image in stone with her son [cum filio] stands in the straight road near St Clement's, the Pope, dismounting from his horse, enters the Lateran for his enthronement.(15)

Another brief mention is in Ye Solace of Pilgrimes, written in about 1450 by John Capgrave (1393-1464), the scholarly prior of St Margaret's at King's Lynn (Norfolk). While visiting Rome he was appalled by the general quality of the available guidebooks, which he found unreliable and out of date, and resolved to produce a more accurate replacement. Nevertheless his Solace contains its own fair share of hearsay and doubtful statements. On Pope Joan's statue it says:

the cherche was deceyued ones in a woman whech deyid on processioun grete with child for a ymage is sette up in memorie of hir as we go to laterane.(16)

Around 1414 Theodoric of Niem, a curial official from Westphalia and co-founder of the German College of S. Maria dell'Anima in Rome, also wrote of the 'marble statue',(17) as did several other authors of a contemporary or later date. Stephan Blanck's Mirabilia of c.1500, for instance, records a 'stone which is carved with an effigy of the female pope and her child.'(18)

All of these commentators mention the statue as an object which existed in their own day. Indeed, the point of including it in books such as the Mirabilia and the Solace of Pilgrimes was to mark it out as a 'tourist sight' of interest to the many thousands of pilgrims who flocked to the city, as a result of the various Jubilees of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Stephan Blanck's edition of the Mirabilia may well have been issued especially for the Jubilee of 1500, in which year an enormous crowd of 200,000 people gathered in St Peter's Square to receive the Easter blessing of Pope Alexander VI.

It seems highly unlikely that the guidebooks would have given space to an entirely fictional monument, while Adam of Usk and Theodoric of Niem, as residents of Rome, would probably not have written about the statue if they had not seen it for themselves. Whether they were justified in making the connection between the figure and Pope Joan is, of course, another question, particularly in view of the fact that it was not associated with her story until the last half of the fourteenth century.

Before leaving the subject for the moment, the amusing case of Pasquale Adinolfi must be mentioned. In 1881 he devoted two pages to the female pope in his Roma nell'età di Mezzo, disclosing an amazing new addition to the evidence. 'There was,' he says, 'a teat, sculpted in marble, for the purpose of attesting that John VII, the Englishman, was a woman and had given birth to a baby.'(19) Disappointingly, Adinolfi's Imago papillae or 'Image of a teat' proves to have been nothing more than a misreading of his source: the late fifteenth century papal Master of Ceremonies, John Burchard. Burchard's Liber Notarum notes the existence of an Imago papissae - not the dramatic teat, but the familiar 'Image of the female pope'.

Another idea which slowly became attached to Pope Joan's history was the suggestion that, because the Church and People of Rome were once hoodwinked into accepting a woman as their pontiff, a pierced seat was afterwards used in the papal investiture ceremonies, in order to check that each new pope was truly male. In this way a repetition of the same error was avoided.

Rumours of the practice began to circulate as early as the 1290s, when the Dominican, Robert d'Usez, recounted a vision in which he saw the seat 'where, it is said, the Pope is proved to be a man'.(20) Such a legend might reasonably have been linked with Joan then and there, but apparently this was only rarely the case to start with. In about 1295 Gaufridus de Collone, a French monk of the Abbey of St Pierre-le-Vif at Sens, wrote that from the female pontiff 'it is said that the Romans derive the custom of checking the sex of the pope-elect through a hole in a stone seat.'(21) Yet most of the earliest chroniclers who referred to the examination believed that it was carried out not only to avoid the illegal installation of a woman as pope, but also to ensure that no eunuch could ascend the throne of St Peter, for a castrated Bishop of Rome was as unacceptable as a female one. The origin of the seat was not generally traced back to Pope Joan in particular until much later. Even in 1404, Adam of Usk saw no reason to connect the 'chair of porphyry, which is pierced beneath for this purpose, that one of the younger cardinals may make proof of [the pope's] sex', with the statue of 'Agnes' mentioned in the same paragraph.

The Englishman, William Brewyn, also failed to make the link when, in 1470, he compiled his fascinating guidebook to the churches of Rome. While describing the Chapel of St Saviour in the Basilica of St John Lateran, he merely states:

...in this chapel are two or more chairs of red marble stone, with apertures carved in them, upon which chairs, as I heard, proof is made as to whether the pope is male or not.(22)

Nevertheless, by the time of William Brewyn, who lived in Rome during the reigns of Paul II and Sixtus IV, the association between these objects and Joan was beginning to be widely acknowledged. Aside from Gaufridus de Collone, the first source to maintain that the chair - or chairs - came into use as a direct consequence of the rule of the female pontiff seems to have been John Capgrave, some twenty years prior to Brewyn's work. In the section of his Solace which deals with the Lateran, he says:

And forth in anothir paue of that cloystir is a chapel and there stant the chayer that the pope is asayed in whethir he be man or woman be cause the cherche was deceyued ones in a woman whech deyid on processioun...(23)

The same explanation was known to Bartolomeo Platina, the Prefect of the Vatican Library under Pope Sixtus IV (1471-84). In his Lives of the Popes (1479), he begins by repeating Martin Polonus' version of events and then goes on:

Some have written that because of this... when the popes are first enthroned on the seat of Peter, which to this end is pierced, their genitals are felt by the most junior deacon present.(24)

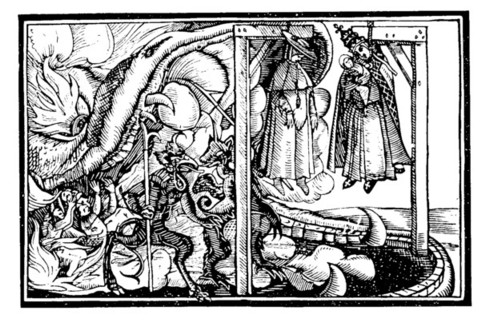

Platina then makes it clear that he believes this assertion to be the result of a misunderstanding, but other authors had no such reservations. After all, scurrilous material of this sort could only enhance the popularity of their works: a very important consideration in the era of that newfangled invention, the printing press. Hartmannus Schedel's Liber Chronicarum, which was published in 1493 by Anton Koberger of Nuremberg, and is therefore more usually known as the Nuremberg Chronicle, gives the standard story of Pope Joan, illustrated with a woodcut of considerable charm [see below]. But at the end of the account, Schedel cannot resist adding that 'the avoidance of the same error was the motive, when first the stone seat was applied to the purpose of the feeling of the [pope's] genitals by a junior deacon through the hole in it.'(25)

Further details are provided by Felix Haemerlein who, writing around 1490 in his De Nobilitate et Rusticitate Dialogus, amply satisfies our curiosity as to the exact form of the ritual. It is diverting to realize that, if he was telling the truth, his contemporary Pope Alexander VI, who was notorious as the father of many children, must have been forced in 1492 to submit to this rather unnecessary test:

...up to the present day [the seat] is still in the same place and is used at the election of the pope. And in order to demonstrate his worthiness, his testicles are felt by the junior cleric present as testimony of his male sex. When this is found to be so, the person who feels them shouts out in a loud voice 'He has testicles'. And all the clerics present reply 'God be praised'. Then they proceed joyfully to the consecration of the pope-elect.(26)

Felix Haemerlein was also the first to take the argument, that the new ceremonial was introduced because of Pope Joan, one logical step further, by maintaining that it was her successor 'Benedict the Third of Roman birth who truly in memory of the event set up the perforated chair in St John Lateran.' The reality of the seat - or pair of seats if William Brewyn is to be believed - and also of the mysterious statue are matters to which we will return in the next chapter. Suffice it to say, at this stage, that they would seem to be the best and most solid evidence for the female pope so far encountered.

We have now looked at all the main facets of the Pope Joan story as it was expanded and modified during the late Middle Ages. A number of other tales were told about her, but they were not repeated with any regularity and failed to gain widespread currency. Theodoric of Niem claimed, for instance, that she had taught at the Greek school in Rome, which was famous for its connections with St Augustine. That she was a woman of considerable literary ability was never in doubt, and some authors laid particular emphasis on this. Martin le Franc, the Provost of Lausanne and a papal secretary to both Nicholas V (1447-55) and the antipope Felix V, mentions the many 'excellently and religiously ornamented' prefaces to the Mass for which she was responsible, in his poem Le Champion des Dames.(27) This idea probably stemmed from the fact that several extraneous prefaces, coming mostly from old Roman tradition, were cut out of the missal at the beginning of the eleventh century. Of course, this reform had nothing whatever to do with the female pontiff.

Such perfectly orthodox literary endeavours were not enough for the German Protestant 'H.S.' who, some years later in 1588, remarked that Joan or 'Gylberta' had 'it is said writ a Booke of Necromancie, of the power and strength of deuils'.(28) He may have copied this from André Tiraqueau's De Legibus Connubialibus which first appeared in 1513. Tiraqueau (1488-1558), the French legal humanist and friend of Rabelais, used almost identical words concerning 'Gilberta', who 'it is said wrote a book of necromancy'.(29) As we have already seen, Tiraqueau and 'H.S.' were by no means alone in suggesting that she must have had the active assistance of Satanic forces in gaining her position. Stephen of Bourbon was the first, but the ultimate example has to be Dietrich Schernberg's play Ein Schön Spiel von Frau Jutten in which 'Jutta' is little more than Hell's pawn, although the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary eventually saves her from eternal damnation.

It would be simplistic to assume that demonic powers were incorporated into the story purely because people could not accept that a 'mere woman' might have had the intelligence and ability to attain such heights in her own right. The medieval mind being what it was, saw hints of witchcraft and sorcery in anything or anybody a little out of the ordinary, and more than one pope was unjustly accused after his death of practising the black arts. In the case of Gerbert of Aurillac, who became Pope Sylvester II (999-1003), it took no more than his immense learning, some of which was acquired under Arab teachers, to convince later chroniclers that he must have signed away his soul in exchange for knowledge and supreme power. The malicious rumours, needless to say, were unheard of during his lifetime. Joan was not even unique in being linked with a grimoire, as the existence of Pope Leo's Enchiridion and The Grimoire of Pope Honorius attests.

Unlikely and fantastic legends grew up around a great many figures, both real and fictitious, in the course of the Middle Ages, but although the female pope had more than her fair share there is every reason to suppose that she was generally accepted as a historical personage for most of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Around the middle of this period she was even included in a long series of papal busts which were made to decorate the nave of Siena Cathedral in Tuscany. Placed between Leo IV and Benedict III, and accompanied by the inscription 'Johannes VIII, Foemina de Anglia', her image was undisturbed for nearly 200 years.

The series of terracotta busts still remains in Siena to this day. It consists of roughly 170 representations, of popes ranging in date from the first century to the twelfth, although the sequence is not always reliable and some pontiffs are repeated while others are omitted or replaced by antipopes. Regrettably, anyone who looks for Pope Joan among them today will search in vain, for her bust was removed in about 1600 on the instigation of Clement VIII.

There is some disagreement as to what then became of the image. Cardinal Baronius (1538-1607), the Vatican librarian from 1597, claimed that it was immediately broken up. Although he seems to have been involved in its removal, and may have been the person who suggested this course of action to the Pope, he could well have been mistaken about its destruction. Slightly later sources state that the Archbishop of Siena under Clement VIII did not wish to see the carving go to waste, so had it altered to represent a different pontiff and then reinstated. The transformation could have been achieved very easily by doing nothing more than changing the inscription, especially since the busts were never intended as true likenesses. The Archbishop might then have preferred not to inform either Baronius or Pope Clement of his unauthorized act.

The indefatigable T.F. Bumpus, in his Cathedrals and Churches of Italy, says that the new depiction was of Alexander III (1159-81), but he is almost certainly wrong. Earlier and quite reliable writers identify it as Pope Zachary (741-52).(30) As the busts are arranged at the present day there is, in fact, no extra figure between Leo IV and Benedict III. Zachary appears in his correct chronological position, separated from Leo IV by Stephen II (752), Paul I (757-67) and Sergius II (844-47). However, in about 1802 an attempt was made to put the papal series into a more logical order, and Zachary's current location may well be the result of this operation.

The story of Pope Joan became so firmly established and widely believed that she was not only commemorated in sculpture, but also used to make general theological points without any questions being asked about her authenticity. Thus the Franciscan philosopher and theologian William of Ockham, the Venerabilis Inceptor, cited the example of Joan - although he did not name her - during his disagreement with Pope John XXII (1316-34). John XXII had issued a Bull in 1329 attacking the Spiritual party among the Franciscans, who clung to their founder's teachings on poverty, in the face of the maturing Order's natural tendency towards a comfortable institutionalism. The Spirituals had been producing tractates aimed against the Papal See, and some of the friars even insisted that the present incumbent was none other than the Antichrist himself, so the Bull was not entirely unreasonable in the circumstances. But William evidently thought it was. His reply, the Opus Nonaginta Dierum written in about 1332, went to great lengths to show that the papacy was not only corrupt, a state of affairs which was hardly news to his readers, but also heretical. In his list of past pontiffs who had not been 'pure, clean and saintly,' he includes 'the woman who was venerated as pope', with no indication at all that he regards her as less real than the others, for 'it is held in the chronicles that she was revered as pope by the universal church for two years, seven months and three days'.(31)

Similar, but more extreme, anti-papal sentiments were expressed by the Bohemian reformer, John Hus, the former Rector of Prague University. He made use of Joan, under the name 'Agnes', in the course of his evidence at the Council of Constance, which was convened by the Pisan antipope, John XXIII, in 1414-15. Hus' argument was that the only true head of the Catholic Church was Christ himself, and that consequently the Church was quite capable of functioning without a terrestrial head during those periods when a corrupt or false pontiff, not predestined by God, was seated on the papal throne. It was for this reason, he explained, that the Church had been able to survive even though its members had been 'deceiv'd in the Person of Agnes' among others. The testimony, with its clear implication that all bad popes, including his contemporaries, could and should be deposed, was not exactly guaranteed to make Hus popular with the authorities. He was eventually condemned as a heretic by the Council and burned to death in 1415, despite the Imperial safe conduct given to him before he travelled to Constance.

In view of the Council members' attitude to Hus, it seems quite certain that they would have scoffed at his references to 'Agnes' if they had been at all doubtful about her reality. In the words of the eighteenth century historian, James L'Enfant: 'if it had not been looked upon at that Time as undeniable Fact, the Fathers of the Council wou'd not have fail'd either to correct John Hus with some Displeasure, and to have laugh'd and shook their Heads, as they did presently for less Cause.'(32)

Thus was the woman pontiff's existence accepted.

Notes & References:

(For the full titles

and a key to abbreviations, see Bibliography)

(1) Ranulph Higden, Polycronycon (1527), bk 5, f.226.

(2) Quoted in John Jewel, Defence of the Apology; The Works of JohnJewel, IV (1850), p.648.

(3) Giovanni Boccaccio, De Mulieribus Claris (1539), f.63; and Concerning Famous Women (1964), p.231.

(4) Adam of Usk, Chron. Adae de Usk (1876), pp.88, 215. For John Hus see James L'Enfant, The History of the Council of Constance (1730), I, p.340.

(5) John J.I. Von Döllinger, Fables Respecting the Popes of the Middle Ages (1871), Appendix B, pp.280-2.

(6) Boccaccio, op. cit., f.63, and pp.232-3.

(7) Eulogium, Chron. (1858), p.243.

(8) Martin Polonus, Chron. Pont. et Imp.; MGH:SS, XXII, p.428.

(9) Mirabilia Urbis Romae (1889), pp.139-40.

(10) Quotation and illustration appear in John Wolfius, Lect. Mem. et Recond. Cent. XVI (1671), I, p.230.

(11) Felix Haemerlein, De Nobil. et Rust. Dial. (c.1490), f.99.

(12) Wolfius, op. cit., I, p.231.

(13) Franceso Petrarch, Chron. de le Vite de Pont. et Imp. (1534), p.72.

(14) Mirabilia Urbis Romae (1889), pp.139-40.

(15) Adam of Usk, op. cit., pp.88, 215.

(16) John Capgrave, Ye Solace of Pilgrimes (1911), p.74.

(17) See Emmanuel D. Rhöides, Pope Joan - A Historical Study (1886), p.82.

(18) Wolfius, op. cit., I, p.231.

(19) Pasquale Adinolfi, Roma nell'età de Mezzo (1881), I, pp.318-19.

(20) Döllinger, op. cit., pp.49-50.

(21) Gaufridus de Collone. Chron.; MGH:SS, XXVI, p.615.

(22) William Brewyn, A XVth Century Guide-Book to the Principal Churches of Rome (1933), p.33.

(23) Capgrave, op. cit.

(24) See Eugène Müntz, 'La Légende de la Papesse Jeanne'; La Bibliofilia, (1900) pt 2, p.330.

(25) Hartmannus Schedel, Liber Chronicarum (1493), f.169.

(26) Haemerlein, op. cit.

(27) Döllinger, op. cit., p.34.

(28) H.S., Historia De Donne Famose or The Romaine Iubile which happened in the yeare 855 (Eng. trans. 1599), C2v.

(29) André Tiraqueau, Opera Omnia (1597), II, p.188.

(30) OC, III, co1.392.

(31) William of Ockham, Opera Politica (1963), II, p.854.

(32) James L'Enfant, op. cit.

Copyright (c) 1988 Rosemary and Darroll Pardoe