Go to the Archive

index

Go to the Archive

indexIn the late 1950s I was lucky enough to be taken on by Leyland Motors as a student apprentice, staying at Wellington House, Leyland's hostel for students. This may not have been a shining example of training at the cutting edge, but it did have "The Garage", an old stable building which was home to an incredible collection of transport relics, some used as daily transport by students and all the result of hours of devotion, sweat and experimentation.

These hours really should have been spent studying to repay Leyland for the training opportunity it was giving us, but then it can be argued that arranging for Austin Seven parts, Bugatti gearboxes, Scott motor cycle castings and the like to be made in the Works and smuggled out was itself training of a high order, though not on the Higher National Certificate syllabus.

Enter the motorised bicycle engine.

Enlightened Leyland management had set up a competition for an illustrated lecture, which was open to students, apprentices and anyone under 25.

My entry was to describe the development of something I thought, in my innocence, was a breakthrough in internal combustion engines. As well as my trusty Cyclaid and other machinery, I had two well-worn 49cc Mini-Motor engines lying idle, and I wondered if the effective piston stroke could be doubled by joining the engines at their heads, allowing the induction from one carburettor via one crankcase to do more work before exhausting through the ports.

Occupying time which should have been spent studying, drinking, or chasing girls, I soon had the two engines joined at the heads by a turned collar, courtesy of the apprentice machine shop. Only one spark plug was needed, which was fortunate, since only one flywheel magneto worked between the pair of engines. Two carburettors were available and so were duly fitted, but with fuel feed to only one.

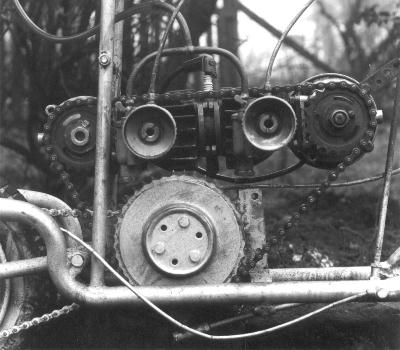

What do you do with such an engine once it has been made? How do you keep the cranks in phase? How do you start it? Will it start? Spurred on by my peers curious to see if this object would work, I welded together a collection of tubing, pram wheels, bicycle chain, and three-speed motor cycle gearbox with clutch to make a small scooter that was christened the Welling-Tonboot. It seemed funny at the time! A long chain ran over sprockets on both crankshafts, in place of the tyre-rollers, and then round the clutch, tension being provided by a large spring hooked on the front crankcase.

Did it run? Not at first, even after much organised pushing around the Wellington House football field. Not at the second attempt either, in spite or some dangerous manoeuvres behind a motorcycle in an attempt to frighten the engine into life. Back in "The Garage", someone suggested rolling the back wheel of the Welling-Tonboot against the rear wheel of a handy Triumph Speed Twin, set up on its rear stand, which would allow some tinkering while the engine was turning. The owner of the Speed Twin suggested that the second carburettor be fed with petrol. Success! With a 98cc roar and a whirr of tortured chain, it ran!

An illicit, untaxed and uninsured high-speed (30mph) run along a factory road gave me the confidence to write a paper on my work for entry to the Lecture competition.

The judges were eminent Leyland engineers such as Norman Tattersall, who later designed the headless 0\500 engine; Mr Cooling, designer of the 0\600 and 0\680 engines, I believe; and Mr G Waring, in charge of research.

It would be nice to say that my paper won. But I cannot remember what the prize was, so it obviously did not. I do remember that during questions after my formal presentation, when polite laughter had subsided, one of the judges asked me pointed questions about the scavenging of my engine and whether I had considered arranging for the cranks to be s1ightly out of phase, allowing the pistons to reach top-dead-centre and uncover ports at different times. Believing that I had invented the opposed-piston engine single-handed, I did not understand the relevance of these questions until much later when I discovered the Leyland T60 tank engine, which had been under development at the time. This was an opposed-piston, blown two-stroke diesel with two crankshafts geared together. I also discovered the Rootes TS3 engine, the Junkers Jumo and, even further back, the Gobron-Brillie. They had all been there before the Welling-Tonboot, but the thrill of creating something unique and seeing that creation burst into life is something I shall never forget.

Unfortunately, the crude and experimental techniques I had used to make the engine, did not last very long, and the crankshafts did get out of phase and each piston merely chased the other up and down the bores! So, having proved to my satisfaction that it worked, I started to play with other things, like a 'chain-gang' Frazer-Nash.

I did not leave motorised bicycles entirely behind me (and having joined the NACC I want to take up the interest again), because the Cyclaid I had bought new in 1955 (for £15!) was adapted to drive through the 3-speed hub of my Hercules "Safety Model", which made it very interesting to ride! The higher gearing and free-wheel enabled me to achieve a fuel consumption of 312 mpg. Very useful at the time of Suez and petrol rationing!

So, if anyone out there has two identical small engines, which are not too rare and precious to be sacrificed on the altar of experimental science, I hope the tale related above will show that "two can be made into one".

First published, June 2001