Go

to the Archive index

Go

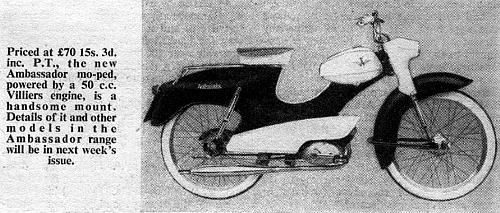

to the Archive indexNovember 1961, sweeping curves, dashing lines and a striking contrast of black & white. The hand behind the pen could have been Mary Quant, but this stunning up-to-the-minute creation was the work of—Ambassador!

The Ascot company had become well known for the manufacture of motor cycles since commencing production in 1947 but never got round to making an autocycle, since these were generally an offshoot product of bicycle manufacturers and they had no such background. All their bikes were fitted with practically every type of Villiers engine, and it was probably a natural progression that when they finally got round to producing a pedal-assisted machine that it would utilise the Wolverhampton factory’s 3K motor.

‘Ambassadors have long been noted for their modernity in styling. Now, for 1962, their range is augmented by a moped, sleek and trim enough to rank proudly among the best lookers on the market. Its technical features are as up-to-date as its lines. Powered by the Villiers 3K two-speed unit, and attractively finished in the Ambassador colours of greystone white and raven black, the Moped would appear to be assured a bright future.’

The Motor Cycle—November 1961.

Since Ambassador factored Zündapp products into the UK, accredited motor cycling authorities simply dismissed the moped as being no more than one of these German creations fitted up with the Villiers engine, but no Zündapp was ever built like this machine! The selection of cycle components were quite extraordinary for a home-built lightweight. From headstock to taillight the frame comprised a pair of massive half-pressings joined along the centre line, with a welded central construction dropping down to the swing arm link and side stand pivot. Unusually, no centre stand was ever fitted, and the Earles-pattern forks are unique for a British moped, though the style appeared on several continental machines and points to where the front and rear suspension units originated with their galvanised shrouds and gold plastic moulded end links. Other obviously imported parts were the chromed ‘Pranafa’ hubs which were laced into RW aluminised Westwood pattern rims and shod with 2¼×19" whitewall tyres. And that ‘Pranafa’ rear hub - it’s so unusually wide with such a ‘leaning’ spoke angle that even a professional wheelbuilder was struck to make comment on it! Though the petrol tank may appear visually similar to the NSU S2-3 in photographs, this is certainly not the case as the pressings are markedly different. The single seat lifts from a hidden catch at the back, revealing a tool storage cavity with a pump holder tube disappearing into the bowels of the frame. Behind the seat, the long rear frame/mudguard form is topped by an extra long rack. Miller supplied the rear light and horn hiding away in the nacelle, which also houses the VDO speedo kit and European origin headlamp set.

The cycle package generates contrasting impressions from differing angles. With the Earles forks, nacelle and sturdy mudguard, the front end appearance is strikingly solid. From side views the machine looks aimost scooter like, while from the rear it seems remarkably long and slender. Sitting on the bike, one is immediately struck by how low the fixed seat height feels at only 31", stretch out to the handlebars and you’re in a sporty forward lean. It’s difficult to work out exactly what the Ambassador was intended to be; it’s certainly an enigma!

All sounds pretty fair so far, but the new machine wasn’t without its design flaws. The stock 3K motor was issued to all customers with a 12T front sprocket, which was suitably geared to the Phillips and Norman combinations of 32T rear sprocket (2.67:1 ratio) on the same 19" wheels. Unfortunately the Pranafa hub came with 35T (2.92:1 ratio), leaving it badly undergeared to the competition. To make matters worse, the mismatched Magura twistgrip to allow utilisation of the Villiers throttle cable that came with the motor set, had a physical stop restricting the carb slider to ¾ opening. This combination left the moped particularly gutless, and meant it was revving its nuts off at a top whack of 30mph. The Ambassador owner must have been very disappointed with his new purchase when the Phillips Gadabout, Norman Nippy and Lido riders went burning past on their machines - fitted with the same Villiers 3K engine!

None of the three surviving machines have their original sidepanels remaining, which from the factory photograph appeared so large as to completely cover and prevent access to the carb controls of choke and flood. From a small hole in the frame behind the petrol tank, operation seems to have been accomplished by some sort of remote control wire link, long gone on every example. Presumably this was so frail that it broke in every case, preventing starting, which required permanent discarding of the sidepanels to enable direct access to the carb. Presently the most complete and original of the three survivors, the feature machine has ‘custom styled’ reduced panels to permit side access to the carb controls. Though a 13T front sprocket would return the gearing to normal expectation, this example runs a 14T (2.5 ratio) to take it 16.6% up on how it left the works, (or 8.3% up against normal drive). The overgearing has been compensated with some power increase by boring out the cylinder to 54cc (+0.060"/1.5mm), taking the capacity up by 8%, then facing back the head and reforming of the combustion chamber to raise the compression ratio from 7:1 to 8.5:1. Though visually identical, a different twistgrip and adapted cable now allow full throttle opening—so let’s see how the Ambassador should have gone if it had been engineered a bit better!

Starting requires both flooding and choke, which lifts off as the throttle is opened. A couple of prods at the pedal and, as Villiers’s own type SM10/12mm carburettor breathes fuel into the motor, it’s away with a smooth and quiet exhaust note reminiscent of a muffled vacuum cleaner. First gear always seems to engage with a clunk, but there’s no dragging on the clutch once it’s in, so perhaps it’s an idiosyncrasy of the motor. With the raised gearing on the feature machine, it was half expected to require a little more slipping of the clutch to pull off, however the bike is surprisingly readily away from the mark. Switching up to second is where the ratio catches up, since first proves to be quite low and leaves a big jump up to second. This requires buzzing up the revs in first to maintain momentum through the change and, to put this into context, the ratio gap is a massive 39% wider than on a comparative 2-gear Rex motor! Despite the power increasing modifications to the engine this is a situation that would certainly catch-up on hills and should ordinarily recommend a ‘charging technique’, but this machine resides in Suffolk County, so it’s probably not much of a consideration. As the revs pick up in second, the Ambassador begins to pull its top gear quite strongly so there’s certainly not a case of overgearing; it just seems a case of Villiers’s mismatched ratios. Their motors may have historically acquired some reputation as reliable, though plodding, carthorses but the 3K surprisingly dispels this tradition since it revs as freely and smoothly as any other contemporary moped engine.

The brakes are good, suspension is fine, and the ride quite positive with the whole package impressing as being very taut for a moped, not at all like the ‘flexi-feel’ of many lightweights. Due in part to the cornering confidence, the sidestand scrapes far too easily on the left and really wants something doing about this detracting problem. Untypically of the VDO speedo, the needle swings wildly on this instrument and the mileometer doesn’t work, so useful indications are out of the question, but around 40mph would seem the expectation of this particular modified machine. The 6V×15/15W headlight is utterly useless along dark country lanes since the ‘infinite beam diffuser’ lamp glass takes what little illumination there is, and scatters it everywhere except the road in front of you! Come back, oh great Miller, Prince of Darkness, all is forgiven!

The Ambassador was undoubtedly very stylish for its time, and with a few obvious design errors sorted out, could easily have made a great machine - so what happened to it? Perhaps this is a job for The Moped Detective! Elementary, my dear Watson: from the surviving frame serials of 164, 196 & 220 registered in February and March 1962, and allowing for common manufacturing practice of starting numbering from 100, it’s probable that no more than a couple of hundred were made. Though the company’s founder, Kaye Don, was approaching retirement and sold out the business to DMW in October 1962, the new moped was already gone before this time. With the Raleigh Group choosing to factor Motobécane products after the 1961 season, and subsequently dropping home-produced Phillips and Norman models, the 3K engine was left with almost no demand. Villiers were hardly going to have much further interest in producing the motor once its two main customers had jumped overboard so, once the initial batch of bikes was built up, Ambassador would have found themselves left high and dry without an engine.

Then there’s that frame. Wide use of metric fasteners on the major cycle parts was most untypical of Ambassador’s imperial background, and the red top on the seat (the feature bike is recovered in black) didn’t really fit with the rest of the colour scheme. It was unimaginable that the little Ascot company would have created the enormously expensive set of press tooling required to make the frame sections, tank, nacelle and sidepanels, then only produced a couple of hundred machines. Sure enough they didn’t, but the true source was as unlikely as it was obscure. The stamping of “Solinsen ‘Pranafa’ Grafrath” on the brakeplates gives away the incredible origin as: Solifer from Finland!

How the connection between these two distant companies came about is likely to remain a mystery, but there was a fair bit of conversion work involved to produce the Ambassador. The original Solifer engine featured right handed chain drive and left side exhaust, while the Villiers motor was opposite, with its exhaust on the right and putting the transmission out on the left. This required the rear wheel to be turned around, and brake stop relocating to the other side of the swingarm. The chain guard and its mounts would also have been wrong-handed and required reversing. The Solifer cylinder head had the spark plug centrally located, where the Villiers came out the side at 45° and would have necessitated an access port cutting in the left hand side panel. Traces of what was probably the original red Solifer colour can be found in places underneath the black Ambassador overpainting, so there’s the match to the seat top!

Beyond the initial batch of frame kits, the Villiers engine supply situation probably ground the project to a halt, by which time the shortly-to-be-retiring Kaye Don was well into negotiation to sell his company to Harold Nock at the Dawson Motor Works. Understandably, ‘The Don’ wasn’t going to be bothered to find another engine for his factored moped frame, and Lindh’s artwork tragically became a very limited edition in Britain. Forty years on from the dawn of the swinging sixties, and rare surviving examples of the Ambassador moped are still just—Absolutely Fabulous!

So where does the ‘Buzzing Road Test’ go after the fabulous Ambassador? Well … isn’t it a pity a British company never made a moped with a British manufactured four-stroke engine, but such a machine could only be like some forgotten dream from some far distant planet. Then, like some Messenger of the Gods stepping out from the pages of a Conan Doyle mystery, and back from the brink of extinction—Return of The Lost World?

First published in Buzzing, February 2002,

An updated version of this article was published in Iceni CAM Magazine, January 2025.