Go

to the Archive index

Go

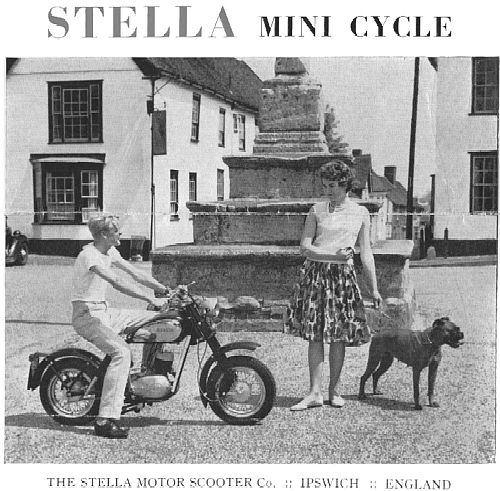

to the Archive indexIf you look through all the reference books, at all the places in Britain that motor cycles have been made, you'll never find anything listed from Ipswich - until now! A unique production machine, completely lost, totally unknown, yet eight identified examples are known to survive. Just as Benz called the Mercedes after his daughter, who was the mystery lady behind the naming of... the Stella? This miniature motor cycle is credited to the design of Maurice Cox, who supported by father Victor Cox and R K O Cooper as co-directors, is believed to have set up the business in 1961. Trading as the Stella Motor Scooter Company, letter headers listed the address from Victor's home at 506 Felixstowe Road, Ipswich; while the bikes were actually built from a unit on Sandy Hill Lane near Ipswich docks. Most of the work seems to have been performed in the evenings since Maurice also held down a full time job as an architect in London, commuting every day on the train. Joined by a moonlighting welder known only as Jock, who worked at Petric Caterpillar Tractors in the adjacent unit during the day, the two are reported to have often laboured long into the night. Backing for the venture seemed to have chiefly come from Victor, who had previously run a movie camera shop in Ipswich and cinema at Manningtree (described as a Tin-Tabernacle sort of building that earlier housed the Paragon Motor Cycle Works 1914 - 1923).

The bike was of tubular frame welded construction with swing-arm rear suspension and long, leading link forks, all seemingly of Stella's own manufacture. The petrol tank was bought in as two pressed halves and welded together down the centre line, then metalwork finished in listed optional colours of red, black, blue, green, white, or yellow. The small, fat wheels comprised a typical scooter type specification of 4" British Hub Co 'Motoloy' full width hubs laced into remarkably wide chrome rims and shod with Dunlop 12" × 3.25" tyres giving a wheel diameter of only 18½", at 3¼" width. The cycle wheelbase was 45½", total length 67", and saddle height a mere 28". The generally installed engine was the 98cc, 2.8bhp Villiers 6F, with 2-speed foot change and kickstart, though a number of machines were also built up with the 4.7bhp Villiers 9F Kart motor variant. While frame number 980121 lists among the five recorded survivors, fitted with a Villiers 4F hand change unit, it could be questionable whether this is the original installation. Several sources suggest 125cc motors were also fitted, however, as yet only one such machine has been positively identified, which was fitted by Stella with a small box sidecar and used about the town of Woodbridge carrying window cleaner's ladders. A prototype scooter was also reportedly being developed, though never seems to have been completed for production.

Forty years separate these two pictures at Lavenham Cross

Initial sales were either direct from the works or through local dealers, and the few surviving vehicles would appear to date from 1962, including the featured test machine, frame number 980145, which became registered on 15th October of that year. This extraordinary surviving example of the Stella marque still remains in the ownership of its very first buyer and, complete with all preserved works literature, currently stands on display at Ipswich Transport Museum. The bike was bought in optional kit form to avoid purchase tax, giving a 15% discount, and further 2½% off for cash sale, so £60.13s.9d - and it's still got the factory receipt! It is of Stella's top specification with the tuned 4.7bhp 9F Kart engine, dual seat, rear footrests, optional chrome panelled tank, fitted speedometer, tool kit and manual. A mere 3,313 miles are recorded on the 70mph Smiths speedo set into the top yoke, and this certainly is the very best example of the known survivors.

A Star...

There are a number of 'original thinking' features about the design, the most striking of which becomes observed as soon as you go to lift the bike off its stand. The only thing to get hold of is the underneath of the dual seat, at which point you realise there is no rear frame section and the passenger half of the saddle is completely unsupported overhang! This means the top mountings on the rear suspension units are taken from an untypically forward location, resulting in the struts leaning at a remarkable angle of 50° from the vertical, which certainly requires stronger than normal springs to compensate the leverage disadvantage. It appears these especially long, undamped units would be of Stella's own manufacture. On the left-hand side, the rear mudguard brackets are taken off the top of the chainguard, and most unusually, the whole back assembly moves with the suspension! Further forward, the front footrest bar crosses the full width of the frame where it also acts as the stand pivot. Handlebars are mounted in a cycle 'central stem' style, and the Miller electrical set is driven direct from the flywheel generator so uses no battery in the system.

Up front, the main fork tubes appear particularly long a result of the small wheels, while at the bottom of these, the dainty leading link arm only extends 4" forward of the pivot to the axle centre and travel in the system is probably unlikely to reach 1½". The Villiers type S.19 carburettor is equipped with flood facility and shutter strangle on the filter, so however cold it gets, you're always going to be able to richen the motor enough to start. Little additional resistance to starting is offered despite the higher 9:1 compression ratio of the 9F 'sports' motor, and administering a few jabs at the kickstart, the engine bursts into life with a deep, mellow throbbing from the Burgess silencer. Even while warming up the engine, it's obvious the 9F variant is appreciably sharper than the prosaic standard units, its responsiveness to throttle and eagerness to rev being most untypical of Villiers factory motors.

Gearshift is located on the right foot, moving up for 1st, and down through neutral into second (top). Winding on the throttle the bike simply surges away, and that Kart motor certainly delivers quite an advantage in terms of the power to weight ratio. This 9F powered test bike actually manages to indicate up to 50mph on the speedo, which on such a little machine, really does feel to be motoring! For those traditional riders who think that proper motor cycles only have big wheels, from the riding position you cannot see their size, and have no impression whatsoever of their small proportions. Between the suspension and fat pneumatic tyres the machine rides quite comfortably, while still proving particularly nimble and surefooted on cornering. Even today the Stella proves a very practical little town bike and is still capable enough for commuting moderate distances - as long as you're not in too much of a hurry!

Stella's breakthrough appeared to come with an export order to the States, however this was to prove the downfall of the enterprise. The story goes... An initial batch of 60 bikes was built up and shipped, only to become held-up by a strike at New York docks. As the charterers failure to unload, the cargo began to accumulate demurrage charges, the shipment became seized in lieu of payment. Everything was lost through no fault of their own, meanwhile, back in Blighty, Stella's pressing creditors forced the business into liquidation! Talk about the good old days! As best can be ascertained this was 1963, and Stella is believed to have only traded for some 18 months, over which period it seems unlikely that production exceeded 200 machines. The source of some of the proprietary components can be identified since a couple of Stella engine numbers notably appear among Villiers records of batches specifically issued to the Excelsior works in Birmingham, while the petrol tank pressings are the same ones used on Excelsior's 98cc Consort model.

The general styling and wide wheels made an unusual combination to our eyes, but across the Atlantic, these different fashions already flourished! Based on the image of period Harley and Indian motor cycles, this very style of minibike had become popularised since 1949 with the Cushman Eagle, Powell P-51, and later Mustang. The constantly pipe-smoking Maurice is quoted as having said to Anglian customers that the Stella was designed and built for on-campus use by American students. Its pioneering 'custom' look was certainly no accident, the individual styling being carefully crafted to another intended market - half a world away!

Despite producing a formal printed sales leaflet, Stella never seems to have attended major shows, so the period motor cycling press never latched on to it. The little bike that never quite made it to the mainstream, simply melted away into local legend - a complete unknown to the wider world! To boldly build a machine from scratch on the fringe of East Anglia, designed for market on the far side of the globe, the Stella was a valiant effort that deserves a far better epitaph than 'Lost in Obscurity'.

The end of which story brings us to that perennial issue - is the Stella really an NACC eligible machine? It has fewer gears than many later qualifying mopeds, while the 6F engine is really little more than a derivative of the earlier 98cc Villiers 2F autocycle unit. Comparable suspension systems and styling appear on other unquestionably qualifying machines, and if it just comes down to the case for pedals, where would the ruling lie on a Brockhouse Corgi? A Di-Blasi folder? Dunkley Whippet, BSA Dandy, Zündapp Falconette, Ariel Pixie, or Puch Cheetah? Any rally organiser would surely be most pleased to have examples of such old and unusual machines turn up for a run. Under pressure from the moped, the last true pedal autocycles largely died out in the mid l950s with the obsolescence of the Villiers 2F. One could argue however, that their spirit lived on in the likes of mini motor cycles such as the James Comet, Excelsior Consort, Mercury Grey Streak, and the extraordinary Stella. Should a vague line of eligibility inhibit Buzzing maintaining what must surely by now be a significant edge in the publication of original machine articles? Would anyone really say the NACC is not a suitable place for the like of the Stella and the rest of the above, or would you actually like to see a pushing of the Final Frontier, and further Buzzing tests the likes of Dunkley Whippet v Ariel Pixie? Let's face it - who else would ever bring you such crazy stuff?

Anyway, on to the next edition, and this clue's another tough one... Unless we can now enter the realm of the Virtual Road Test, how else could one cover an article on a British Cycle Company that never made a production moped? But what if autocycle archaeologists turned up the missing links, and somehow we'd got hold of one of only two prototype show models that appeared at Earls Court in November 1960? Then the first time this machine is ever fired up, is 42 years later for the Buzzing test? Too fantastic to be true, or could fact really be - Stranger than Fiction?

The Stella Mini-bike featured in this article is on display in Ipswich Transport Museum.

First published in December 2002. Since the article was written, more information has been uncovered. A revised and updated article on the Stella was published in the Vintage Motor Scooter Club magazine in May 2010.