Go

to the Archive index

Go

to the Archive indexAs a youth, alert for new ideas, I once came across a magazine picture of a child's scooter with a small engine-driven propeller mounted on the handlebars, no doubt with the hope of augmenting the rider's propulsive effort. Positively dangerous and of no practical use perhaps but, in that moment, an enduring interest in motorised personal transport was born and I spent many fruitless hours trying to figure out how I could install a small engine or electric motor in a bicycle.

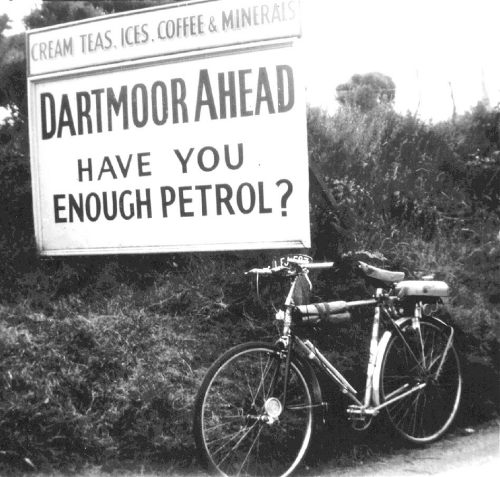

The appearance in the early fifties of a range of petrol-driven bicycle engines was a dream come true and I fitted a Trojan Mini-Motor to my bicycle. It was not the best cycle to receive an engine being a lightweight sports machine and, on at least one occasion, the combination of the mean force due to the engine being forced down on to the back wheel and the vibratory forces due to the running engine, caused the frame to part near the rear axle. Otherwise, the arrangement gave me sterling service for some two years. The benefits of the internal combustion engine were not lost on me and I motored everywhere. I cycled to college every day and nowhere in the town was more than a few minutes away. Distance was no object and I would sit for hours astride a hard saddle on an unsprung bicycle with no apparent discomfort. We lived in East Devon at the time and I frequently visited a friend in Tavistock, crossing Dartmoor over the mountainous B3212 through Moretonhampstead and returning along the less hilly A30 through Okehampton. The engine never failed me and the only trouble I ever had on this run was when the lights failed as I was returning one dark night and I motored the last twenty miles or so clinging to the vaguely visible white line in the middle of the road and not meeting another vehicle. But then, it was 1952.

If the Mini-Motor had any specific problem it was the drive which was crude, but probably the best option consistent with the price and it did work reasonably well. The complete unit, incorporating engine, carburettor and petrol tank was hinged about a bracket clamped to the saddle post. In the non-driving position the drive roller, directly on the engine crankshaft, was held off the rear tyre by means of a spring. Operating a large, chromium-plated lever on the handlebars pulled the engine assembly down against the spring and caused the drive roller to make firm contact with the top of the rear tyre. A latch in the lever then operated to hold the driving roller against the wheel. It had to be remembered that this was not a clutch; roller to tyre contact and disconnection had to be made smartly if unnecessary tyre wear was to be avoided. I quickly became aware of this having ruined the first tyre. On stopping at traffic lights or a "Halt" sign, the drive could be disconnected by unlatching the handlebar lever to raise the roller so that the engine was kept idling. On taking off from this position, it was desirable to pedal up to some speed where the roller and wheel speeds were more or less coincident before re-engaging the drive. When moving with the engine running but discon nected, one had to be careful to avoid irregularities in the road which might suddenly connect the roller and wheel with excessive and uneven wear to the tyre.

The drive roller, which was of webbed cast iron and about 2 inches diameter, was threaded to screw on to the engine crankshaft and was held fast with a locknut. All this was accessible by removing a steel shroud which partially surrounded the roller to protect the underside of the engine unit from thrown-up dirt. At some point it occurred to me that a smooth roller might cause less tyre wear than the webbed version, so I turned and fitted rollers of oak which worked well enough in dry weather but which slipped hopelessly if the tyre was wet. Someone told me that a rubber roller would give good grip and minimise tyre wear so I sleeved wooden rollers with hose of the appropriate diameter but could not get a lasting bond between sleeve and roller. In experimenting with wooden rollers, I tried some smaller and some larger and found the supplied two-inch version to be about the right compromise for acceptable performance uphill and along the flat, although a quite small change in roller diameter created noticeable changes in torque and speed. After a couple of years, I graduated to motor cycles and then, as most of us do, to motor cars.

When I retired,my thoughts turned once again to motorised personal transport and the possibility of electric bicycle propulsion for travelling short distances without getting the car out. At about this time Sinclair's first Zeta became available and I bought one but was disappointed. It was about as basic as it could be, the drive being held on to the rear wheel with a length of bungee and a hook, such as one uses to secure luggage. There was no real control over the motor which was either on or off. It wouldn't go very far on one charge and I thought it underpowered and overpriced, although the innovation of a belt passing over the drive roller and an idler was a step forward in obtaining good friction with the tyre. If you double the supply voltage to an electric motor, the power is quadrupled, so I connected a spare 12 volt battery in series with the existing supply. The machine ran as if it was on steroids but, as was to be expected, it overheated fairly rapidly and would not have lasted long. I could have tried upping the voltage by something less - 6 volts would have doubled the power but, by then, I had decided that I needed a folding bicycle that could be carried in the car, so Zeta was abandoned.

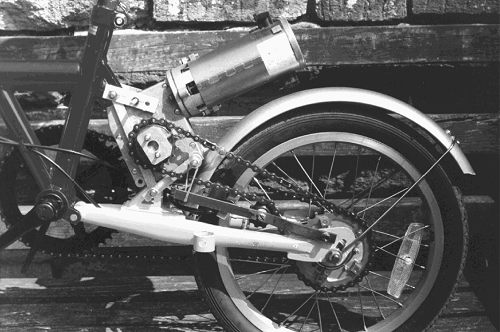

I removed the spring and damper from the rear swinging arm of a Classic folding bicycle with 16 inch wheels and fit- ted in its place a 180 watt EMD (Electric Motor Developments) motor. Through a reduction gear, the motor drove a freewheel sprocket connected by chain to a sprocket on the near side of the rear wheel, the arrangement being such that pedalling and motor assistance could be applied together or independently. The system worked reasonably well with sealed lead acid batteries, but motor control without a DC controller was not smooth and, having put the motor where the carrying rack might have been, I never found a satisfactory place to carry the batteries. Neither the bicycle or the motor were lightweight and I never went far enough to determine how far it would travel on one charge. Furthermore, the whole arrangement was cumbersome for folding and lifting into the car.

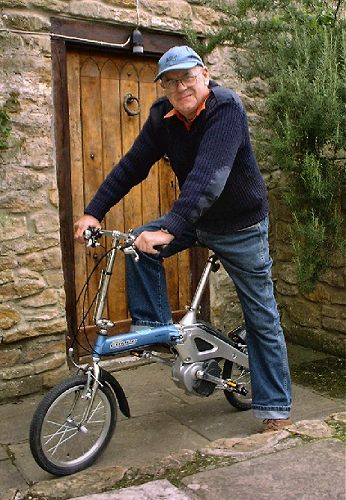

With technological advances in battery and DC motor technology, I considered the possibility of a hub motor in the above-mentioned bicycle, but was quoted £845 for a kit and that did not include the cost of re-spoking the front wheel to take the motor. My most important requirements are light weight and foldability and I finally found both of these in the Honda Step Compo, which was not cheap, although the cost included the bicycle with Shimano 3-speed hub gear. Pedalling is mandatory, a turn or two switching on the motor to provide half the torque requirement, reducing as speed increases. This is great along the flat and up gentle inclines but, on steeper hills, I found I had to pedal vigorously to keep the motor providing its share. I got around this by fitting a larger sprocket on the back wheel, thus reducing the all-round torque demanded and provided. I can now sail up most hills albeit somewhat slower. The motor, rated at 235 watts, is capable of greater power output, but this is kept down and integrated with the pedalling to achieve the vaunted 10 miles range on a 24 volt Nimh battery of only 3.6Ah. I would like to interfere with this arrangement and get more power - albeit at the expense of the mileage, and probably will eventually.

Looking back over many years of motoring, I have to say that, of all the two-wheeled vehicles I owned, the bicycle with Mini-Motor was the most memorable. It was my first powered machine, introduced me to the delights of tinkering with engines and instantly freed me from the agony of continuous pedalling. I could, I suppose, buy a cyclemotor, clamp it to a bicycle and take to the road. But you cannot re-live the past and nothing could measure up to my memories of riding in the golden age of the cyclemotor, fifty years ago.

First published, February 2005