Go

to the Archive index

Go

to the Archive index

In the 1960s, I was already a restorer and rider of early motor bicycles. I rode these in the Banbury run and other events organised by the VMCC. In 1966, I was fortunate to borrow and restore from Percy Clare what was considered to be the great grandfather of motor cycles. This was a Werner from around 1899-1900. Percy had acquired the machine from a VMCC member who had bought it in France from an antique shop for a few French francs.

So what were they like to ride and how did the pioneers such as the great Ixion cope with them? It was with some trepidation that I started to restore it to concours condition and to ride it successfully.

The Werner Frères, Michel and Eugène, were of French nationality but of Russian extraction; they started experimenting with motor bicycles in 1896 using a horizontal type De Dion-Bouton engine. This machine was a failure but, by 1897, they had developed a machine with the engine mount at the steering head of a bicycle driving the front wheel via a belt rim, with hot tube ignition, which sometimes caused the machine to burst into flames, especially on windy days. This was overcome by using the new high tension coil, battery and platinum point ignition. Thus they had a saleable product and set up a workshop in Paris to manufacture these machines throughout Europe. Here at last was something the working man could afford at a price of 45 Guineas and, even in those days, hire purchase was possible.

The Werner of 1899 was a purpose-built motor bicycle of 216cc, and had a strengthened frame with special strengthened forks to accept the Werner Frères own engines. It employed a surface carburettor, which consisted of a separate sealed tank within the fuel tank into which fuel was allowed in by a screw down valve on the top of the carb. Its level was indicated by a float and wire, which gave you the level of fuel within the surface carb. Usually one kept the level at half full, one was also mindful keeping the float controls closed when not in use. Fuel was of 0.680 specific gravity and a pipe led from the surface carb to the induction pipe and thence to the automatic inlet valve of the engine. The automatic inlet valve had a weak spring that could be compressed between light pressure of the thumb and forefinger and had an opening of 5/32 of an inch for best results. Air was supplied by means of a twist grip air valve on the left side of the handlebar, indeed the whole handlebar was fixed to the engine via the sealed steering head and air passed through the left handlebar twist grip. Ignition was via battery and coil to an open contact breaker whose current passed through a removable handlebar plug and a right side twist grip. There was an exhaust valve lifter, two brake levers and an advance and retard lever; there was no throttle and speed was regulated by the right twist grip cutting the current and the air control twist grip. Atmospheric conditions also upset the mixture as did road surfaces.

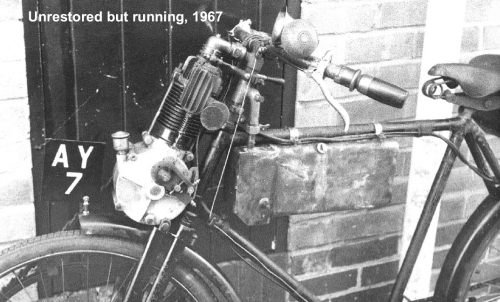

On acquiring the Werner from Percy Clare I decided to get it running for the 1967 VMCC Banbury run, this required renewing all cabling, the fitting of an additional brake system to conform with the law (it only had a band brake on the rear hub), renewal of the rusted inch-pitch chain and correct twisted round section rawhide belting for the final belt rim drive. After several months, all these things were done and all that remained was to put some 0.680 spec grav fuel in the tank, prime the carb and try it. It was with some trepidation that I wheeled out this genuine Paris-built Werner on a warm May morning. I was pleased that this Werner was not the Lawson MMC licence-built Werner (a different animal) but the true Great Grandfather of every motor cycle on the road. I was aware of the fearsome reputation that these early pioneers had, especially with their centre of gravity, their side slipping, their narrow tyres and their desire to commit "suttee" and incinerate themselves (and their riders on occasion). Indeed, the great Ixion described such happenings in his writings. But all went well; I live on a slope and did 15 miles that morning and stopped to take stock, to replenish the carb and to top up the large oil cup and wick on the front crankcase of the engine. Again I pedalled a few feet and away she went; I felt confident enough to try advancing and retarding the ignition, also to cut the engine in and out with the right twist grip. All went well and soon we were back at Kirby Muxloe.

I entered her for Banbury that year and, because of the historic importance of this machine, I felt that Edwardian dress was appropriate so I sported a striped blazer, straw boater, and an Edwardian moustache. This did not go down well with some members of the VMCC and I was accused of "Comic Pantomime" dress. I was used to riding in Bicycle events in just such dress, as do most riders in the bicycle world to this day. It all adds to the era we were all so desperately trying to emulate with our machines. I rode her as No.1, away she behaved like the Prima Donna she was and galloped the 16 miles easily. That autumn I entered her for the Coventry Parade from Stoneleigh Abbey to near Birmingham, this was in the September. We started off OK but soon a thunder-storm developed whilst I was en route, this had dire consequences on the Werner and me. The ignition shorted via the handlebar to my bare hands and I was glued to the handlebars and as a fellow rider put it "yelping" with blue sparks around my face and hair (I must have looked quite a sight). Anyway I fell off her and waited until the storm had passed before I dared to remount. I was the last back and search parties were being contemplated. I remember the cheer as I arrived back, it was wonderful, but as I leapt off the machine the front wheel axle snapped.

It was too much for her, so I decided to re-build her completely to concours condition and this I did over two years, and everything was done to bring her back to factory-new condition, and I rode her for the last time again at Stoneleigh, she was tired and, at the end of the run, I noticed fatigue cracks in her crank case. I never rode her again; I cleaned her and said to her "well done thou good and faithful servant, you have carried me well and never willingly bit me". I loved that machine and I felt privileged that I had the experience of riding her and learning so many of her secrets; she was from the dawn of the motor cycling era and there are so few of us left to relate as to what it was like to build and ride such wonderful machines. I returned to my Excelsiors, but that is another story.

Michel and Eugène Werner were born of a Franco-German father and a Russian mother. The mother had escaped with her parents from Russia in the 1880's during the time of the Czarist Pogroms of the mid to late 19th century. She met and married Werner about 1862. They lived in Paris, as did many Russian emigrés. Their two sons were well educated in Paris. They had a mechanical interest, and began experimenting with motor bicycles in 1896. They were men of great vision that gave us the motor cycle industry of today. They gave us in 1902 the first motor cycle with the engine incorporated into the frame, which is the conventional way we use today; they were also amongst the first to use both the inlet and exhaust valves mechanically operated.

Their basic design of engine over the front wheel survives to this day in the VéloSoleX and, in the 1950s, cyclemotors such as Cymota and Mocyc.

I had many happy rides on the Wemer and preparation was always vital. For instance a complete air tight carburetion system, (save for the normal mixture needs), good batteries, oil injection every 15 miles, and also a shot of oil via the priming valve every so often and she would run very well. One thing I did before I ever put the Werner on the road was to replace the exhaust valve spring. This is vital if you want to get a pioneer to run properly and give continuous power. It is also wise to use a valve spring that is made of the proper valve spring material, which won't diminish in strength when hot. The longest ride I ever made was 73 miles with no trouble, although I carried a spare gallon of fuel with me. I loved the slow thump of her engine, I was always aware of the side slip, I shunned wet weather, loved, as she did the warm sunny days, I dodged the cool shade for fear of upsetting the mixture, we were in harmony, she and I. We did many rides together and it is something I will always treasure. She was a lovely dinosaur from a more elegant era, and needed tender loving care, and when the time came to part with her it was with a lump in my throat, for who of my peers could say that they had ridden and cared for such a wonderful treasure?

First published, April 2005