John Marston

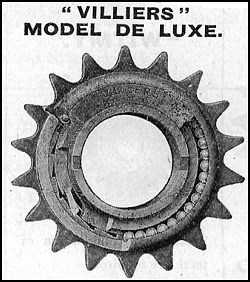

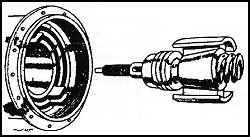

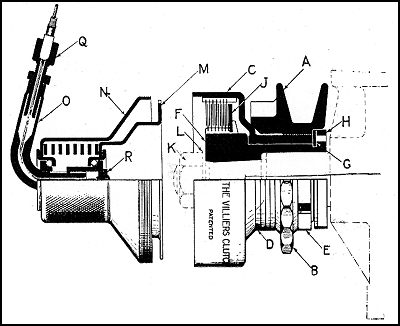

Villiers freewheel

In 1898, John Marston was building a pedal cycle which he named The Sunbeam Cob. His company had a very high reputation for the work it had been doing for some years as a Japanner and Tinsmith, and he was anxious that the cycle should be made to that tradition. When he found that the pedals he was buying in at that time did not keep up to it, he sent his son Charles to America to find if there was a better way of doing the work, and if so, to buy the equipment required. Charles bought the equipment from Messrs Pratt and Whitney of Connecticut and arranged for it to be shipped to Wolverhampton. Unfortunately when it arrived it was found to be too big for the factory, so John bought an engineering firm, E Bullivant, moved the machinery in and put Charles in charge of the firm. As it was sited in Villiers Street, they named it The Villiers Company [Note 1].

Before long they were able to supply all the requirements of the Sunbeam Company and sell surplus stock to other traders, and soon all the best cycles were fitted with Villiers pedals. By 1902 they were well established and looked at the demand then being created for freewheels for the cycles. After experiments, they devised their own and offered it to the market. Some time after this, Charles bought the company from his father and soon decided to stop making pedals and concentrate on freewheels.

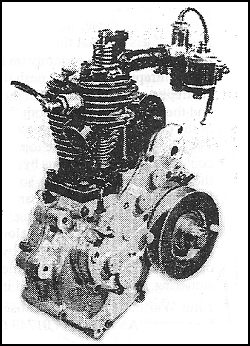

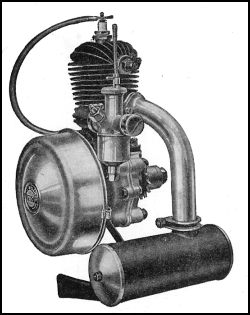

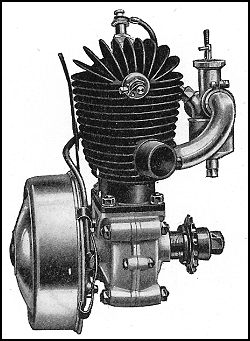

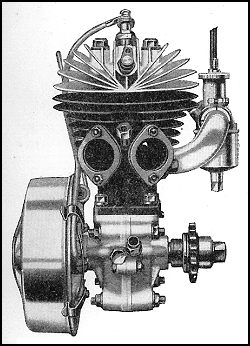

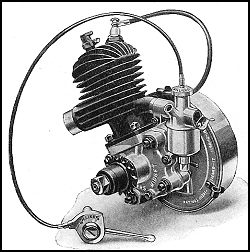

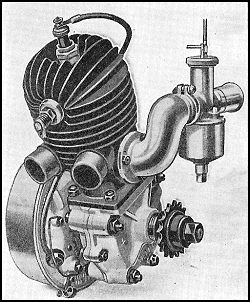

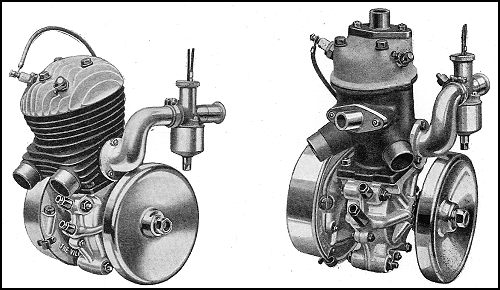

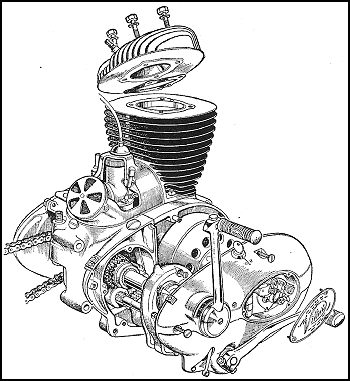

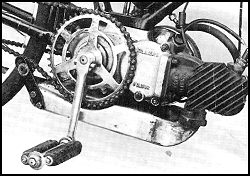

The motor cycle had been developing then for some years and they noticed that most machines were of fixed gear type with a run and bump or pedal start. So they introduced their first motor cycle part, a ‘Free Engine’ rear wheel hub. This was to be developed over the next few years with various models being produced. In 1912 they introduced their first motor cycle engine, an inlet over exhaust 350cc four stroke with a built in two speed gearbox and clutch. It was well reported in the motor cycle press but, although various users claimed good results from the machine, builders did not take to it, claiming it was too complicated.

350cc ioe engine of 1912

They went back to work and by the end of the year produced their first two stroke. It was of 269cc and proved to be the start of over 3,000,000 similar engines made in over 80 different models for motor cycle, scooter and light car use, which were sold in some 500 different countries, in addition to many special models of both 2 and 4 stroke engines made for other purposes which I do not intend to cover here.

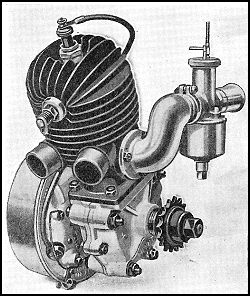

Villiers free engine hub

The cylinder had a fixed head, as was usual at that time. The bearings for crankshaft and small end were of phosphor-bronze and the big end a roller bearing. The piston was a deflector head type in cast iron, the exhaust pipe and expansion box were aluminium. The lubrication system was usually by hand pump from the oil tank, built alongside the petrol tank. The oil was passed through a drilled front crankcase bolt into the crankcase where cast on oilways fed it to the bearings. Surplus oil was splashed onto the walls where it was picked up by the incoming petrol vapour and taken to the upper cylinder. This engine was designated the Mark Ⅰ and given the prenumber code O. Can I break off my story for a few moments to say that I have been trying to work out how Villiers set up their pre-WWⅡ engine codes? The Marks Ⅰ, Ⅱ, Ⅲ, Ⅳ and Ⅴ seem reasonable, but why the stamped engine codes were 0, A, B, C, and D, I have not been able to find out, and whether there was a reason to follow this possibly logical method with some of the coding we will meet later I simply cannot find out; if you know any better I will be interested to hear.

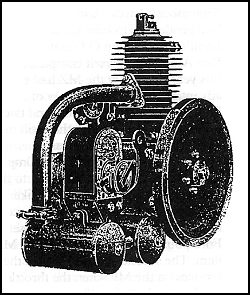

In spite of the disruptions caused by the start of the Great War in 1914, they continued to supply engines and in 1916 introduced a new model, the Mark Ⅱ. The main change was in the exhaust system which was now made in steel. The method of holding the exhaust to the cylinder was also changed and spares lists for the period noted that no more Mark Ⅰ cylinders would be made, but that the Mark Ⅱ would be issued if replacements were required.

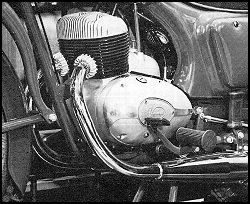

Mark Ⅱ 269cc

two-stroke engine

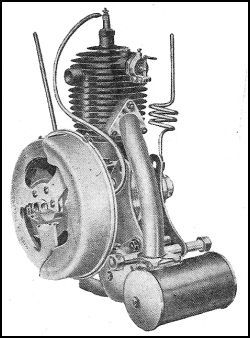

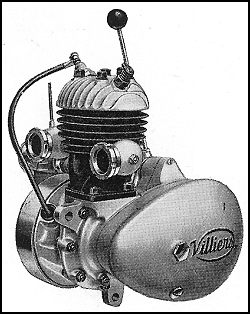

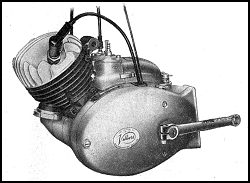

Further changes were made in 1920 when the Mark Ⅲ was produced. The exhaust was again improved, the driving shaft altered and the crankcase and bushes improved. The outside flywheel was made with a separate centrepiece which could be changed to allow for pulley or sprocket to be used. A further change in the driving shaft produced the Mark Ⅳ in 1921, this allowed the flywheel magneto to be fitted and from the Mark Ⅴ in 1922 all Villiers engines made for the next 35 years had one fitted, although a few machine builders used other variations. The flywheel magneto was devised by Villiers director Frank Farrer. During the war all supplies of Bosch magnetos, the magneto used by most machines, except for a few produced in factories in France and Canada were stopped and British machine builders had to look for supplies from other makers. Frank was sitting at his desk when his eye caught sight of the flywheel assembly of an engine and he built up a magneto using corks and two lady’s hatpins. It worked and he patented the idea. Further development had to wait until the end of the war when Frank Pountney was given the task of developing it further to produce a working unit. The fact that it had run for so many years is proof of the work they did. Frank Farrer became managing director of the company in 1919 when Charles Marston became chairman.

Mark V 269cc engine

Introduced during the period of the Marks Ⅳ and Ⅴ was a free engine clutch which could be fitted to the drive side of the crankshaft, unfortunately it cannot be fitted to earlier engines. It sold for £2–15s (£2.75p) and only took 15mins fitting. It was said that ‘The rider only has to walk the machine a few yards until the engines fires when but a slight depression of the clutch lever is required to bring the machine to a standstill. The rider can then take his seat, release the clutch lever, and ride leisurely away’.

Another advantage brought in for the Mark Ⅴ and useable on the Mark Ⅳ was electric lighting. For an extra £4–10s (£4.50p), lighting coils could be added to the flywheel mag. The current was only available with the engine running so dry batteries were used for parking lights, but as very few lighting sets were available at the time, it was another introduction by Villiers for the lightweight machine.

For the 1922 season, Villiers made a bold move; they scrapped the 269cc engine and introduced a range of 147cc, the Ⅵ C (prefix H), 247cc, the Ⅵ A (J), and 342cc, the Ⅵ B (K) units. The three units were basically the same. The flat fin heads now sported a "sunburst" pattern which gave better cooling. A single exhaust port and an intake port facing forward with the carburettor bolting directly onto the cylinder were fitted. All had the flywheel magneto which included lighting coils, a ‘small’ magneto measuring some 7½" diameter was used on the 147cc engine, with a standard 9" diameter magneto on the larger engines. The ⅥⅥ C and Ⅵ A used petroil lubrication and the Ⅵ B had drip feed lubrication. These engines were improved over the coming years with the Ⅷ C lasting until the late 1940s, but more about them later.

Villiers very rarely entered the competitive area but many clubmen and some firms were already using Villiers engines to win awards. In 1923 Tommy Meeten, the founder of the BTSC used a 147cc engiried Francis–Barnett at Brooklands and won a 3 lap handicap race and a 5 lap event, averaging 46.03mph. He was awarded the Harry Smith Gold Cup for his efforts. In the 1923 Scottish Six Days Trial, B Carter entered a Carfield Villiers machine and gained a bronze medal, while two Harper three-wheelers fitted with 269cc engines won the bronze and silver medals.

Villiers Free Engine Clutch

The introduction of the new range of 147cc, 247cc and 342cc engines proved a popular move and the development of these engines progressed rapidly over a number of years, with the Mark Ⅶ C engine being introduced in 1923 and the Ⅶ A, and Ⅶ B in 1924 with the Ⅷ C. The ‘A’ mark numbers went up to ⅩⅧ A in the 1930s with the ‘B’ mark going to ⅩⅦ B. Both had some unused numbers and there were engine changes in each, but the ⅩⅧ C was available until 1947, with the only change the introduction of the Ⅻ C and ⅩⅤ C engines in 1932 and 1934 respectively. The Ⅵ, Ⅶ and Ⅷ C engines had a bore of 55mm and a stroke of 62mm, while the Ⅻ and ⅩⅤ C had a bore and stroke of 53mm×67mm.

Mark Ⅷ C engine

Mark Ⅻ C engine

Villiers used Roman numerals in quoting mark numbers for most of their engines up to 1945 [Note 2].

A new capacity class, the 172cc, was brought out in 1924. This was to form the basis of two engines which were to bring world records to a number of companies. The first engine was the Sports Engine (no mark number was allocated to these engines). After a short period the Villiers Automatic Lubrication System was introduced and a second Sports Engine, this time with the Automatic System was introduced. They have the engine prefix ‘T’ for the Sports and ‘TL’ for the Sports fitted with Autolube, as it became known. The engine had a bore and stroke of 57.15mm×67mm. Various machine builders and private firms started tuning the TL engine and our Founder, Tommy Meeten, used this engine, as well as others, to win various races on the Brooklands track. Villiers themselves started tuning the engine, raising the compression ratio, altering the ports, varied the bottom end and increased the output of the flywheel magneto to produce a special racing magneto, and added an alloy head to produce a racing unit which they named the Brooklands Engine. At the same time they introduced the Super Sports TT. This had an alloy head and a higher compression ratio than the Sports and was an intermediate between the Sports and Brooklands. It was used in many long distance events, again breaking records and winning high awards.

There are too many awards to list, but some of the more important include:

Enough of records.

The vast majority of these machines were fitted with the Villiers Automatic Lubrication System. Prior to this time the majority of two stroke engines had relied either on a drip feed system or a Petroil system. Villiers were the first to develop any form of automatic oiling system for machines of the lower capacities. When working correctly it was an excellent system, as records such as those quoted show. Some riders, mostly those of the ‘commuter’ type, found it difficult to handle. They were given the choice of models with Automatic or Petroil systems by most manufacturers.

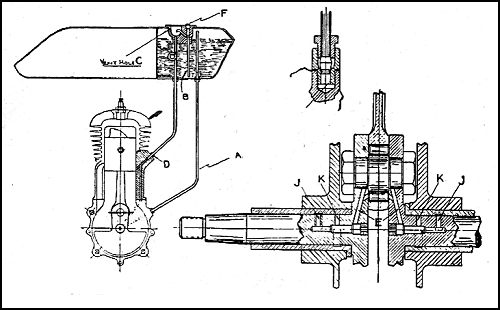

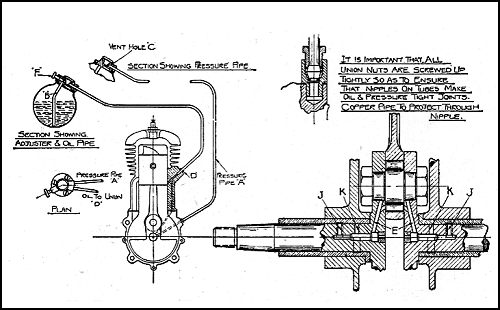

Mark I automatic lubrication system

An oil tank situated on the rear down tube, or as a portion of the petrol tank, was used (Marks I, Ⅱ and Ⅲ as shown). A tube fed pressure from the crankcase into the tank and a vent hole in the sight feed kept the pressure at 4lbs per square inch. This pressure fed the oil through a sight feed to the crankcase. An adjustable screw enabled the flow from the tank to the crankcase to be regulated. The oil was led to the main bearings and surplus oil was picked up by the incoming petrol vapour and fed into the upper cylinder. The important factor was, of course, that as the speed of the engine increased, so did the oil supply.

Mark Ⅱ automatic lubrication system

One problem was the need to maintain a leak-free system. If any leaks occurred then the pressure would drop and the system fail. The same applied if the vent hole was blocked and the pressure increased above the 4lbs per square inch. The practical motorcyclist of the day could cope with it quite easily, but those who could not undertake their own maintenance found problems and the system was dropped by the end of the ’30s—to be used again, of course, on modern two strokes! 1926 saw the introduction of the first 125cc model, the Mark Ⅵ D 1¼hp engine. This was very much in the same pattern as the 147cc engine having a fixed cylinder head with roller type big end, but had twin exhaust ports. It did not find a high acceptance but was available for a number of years. 1927 saw the first Villiers Twin. It was 344cc with aluminium pistons, three large plain bearings, and was built in unit with a three speed gearbox and clutch. The automatic lubrication was fed from the crankcase and the flywheel magneto was placed in front of the engine. Francis–Barnett built its Pullman model to use this engine, Sun made a few machines with it and Monet–Goyon and La Mondial used it on the continent. Press reports gave it high praise and it was used in competition as well as a road bike but it did not capture the imagination of the buying public and was withdrawn after a short period.

Mark Ⅱ E engine

Super Sport engine

The late twenties saw the introduction of an engine which was to stay with Villiers for the rest of their time, the E class 196cc (later amended to 197cc). The I E engine was available with Autolube or Petroil lubrication. It had a fixed cylinder head, a variable ignition system and a twin exhaust system, similar to the 172cc models. A Super Sports engine fitted with a detachable alloy head was introduced in 1929, and the Ⅱ E with Petroloil and a single exhaust in 1930. The I E ran until 1938 and the Ⅱ E and 196cc Super Sports until 1940.

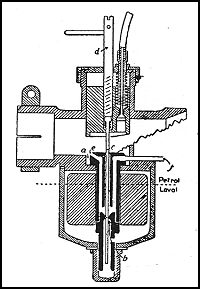

The first Villiers

carburettor

In 1926 Villiers bought the Mills Carburettor Co and renamed the carburettor ‘The Villiers’. For many years afterwards all Villiers engines were offered with a suitable carburettor fitted although a few firms still used another make.

In 1927 developments were made with some engines so that they would be more suitable for various industrial and domestic uses. This was to lead to a large increase in business and the production of various special engines when these were required.

In 1926 Charles Marston was honoured by His Majesty King George V with a knighthood. In addition to his work in the company, Charles had become an active member of both the Church of England and the Conservative Party, representing the county on the highest levels of both. In addition he had taken part in and supported archaeological surveys in both this country and the Middle East. He had been a JP for the last twenty years.

Another engine produced in the late 20s was a 500cc twin. This time the cylinders were placed side by side. Unfortunately no specifications were published. Three engines were made and a sample sent to Brough Superior and SOS in England, and to Monet–Goyon in France. SOS did not make up a machine to test the engine but Brough and Monet–Goyon did. No road tests were published and the engine was never produced in quantity, but I’m pleased to hear that both the Brough and the Monet–Goyon have been rebuilt and exhibited at various events.

Most of the engines introduced in the latter twenties were developed further in the thirties but the Super Sports and Brooklands 172cc models were dropped after a few years. There were, in addition, the development of various new engmes.

Villiers Midget engine

The first of these was the Midget, a 98cc engine which was taken up by a number of firms to produce a very economical machine which could be offered at a very low price. This was, of course, the period of depression with up to 3,000,000 unemployed workers, and those who could find work were often very restricted in the money they had available, so a machine which would cover up to 200 miles on one gallon of petrol was an attraction. The Midget introduced another new pattern in the Villiers engine construction with its exhaust and transfer ports placed at the side of the cylinder in line with crankshaft and a retaining disk being used to prevent the gudgeon pin entering the transfer port. The cylinder and head were still cast in one piece and a cast iron deflector type piston was used. Roller bearing big ends and a force fit crankpin completed the job. The cylinder was upright as usual, and petroil lubrication was used.

The machines produced were fitted with 2 or 3 speed gearboxes and priced in the £15 region with the Excelsior, priced at 14 guineas (£14.70p) being often claimed to be the cheapest motor cycle ever made. It needed another 30/- (£1.50p) if you required lighting. A number of other firms were very near on price and even Triumph used the engine to produce their Gloria lightweight. Most of these models were available until 1940.

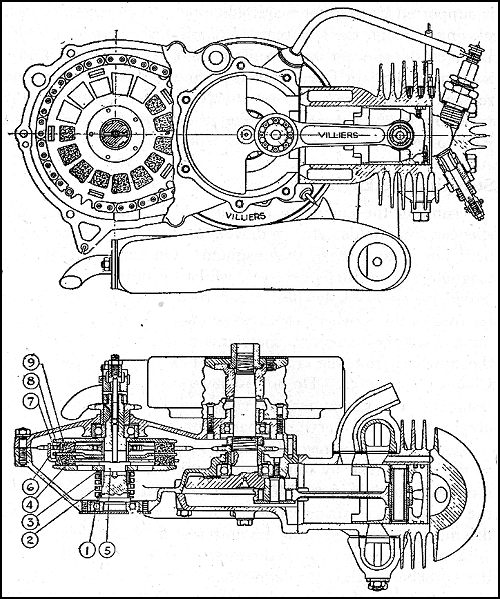

Another 98cc engine, the Junior, was introduced in 1937 [Note 3]. This time the aim was to capture the increasing market for autocycles. For this purpose the engine lay flat with the cylinder facing forward. The piston was of aluminium alloy but still with a deflector head. The big end had alternating steel and bronze rollers, the crankshaft mounted in ball bearings, and the crankpin overhung the casing. A clutch was built into the casing.

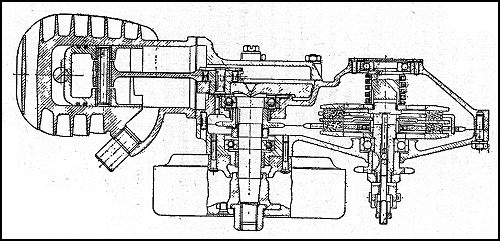

Horizontal section through the Villiers Junior engine

Before leaving these engines, both of which were available until the Second World War stopped production, mention must be made of an unusual use of the Midget engine in the Stanley Tricycle, a standard type of tricycle which used the Midget engine to provide the rider with additional power when required. Larger engines are reported to have been fitted at a later date.

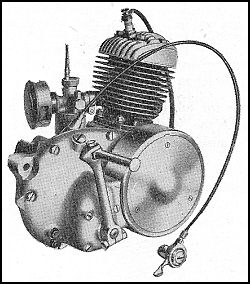

Mark 9D engine

The D type 122cc engine was reintroduced as the Ⅷ D in 1936. it had a bore and stroke of 50×62mm. The cylinder barrel was fitted with a separate head and a flat topped piston was used, exhaust studs were placed on both sides of the barrel and the carburettor stub on the offside. Four transfer ports were built in and roller bearings were used on the big end with the usual bronze sleeves on the main bearings. The small end was fully floating on a bronze bush, the flywheel magneto was fitted with a two-pole system and covered by a flat alloy plate held on by three screws. A hand change three speed gearbox was built into the unit. The Ⅷ D [Note 4] was given the prefix AA and in 1938 further development was introduced as the 9D. This now had a 6 pole 18 watt flywheel magneto, this time fitted with a flat aluminium dust cover as used on the Ⅷ D but with a dome in the centre to cover a hammertight nut. Also introduced were small improvements in the gearchange which was still a hand operated system. The prefix used on the 9D was AAA [Note 5].

As I have already remarked, a number of the engines developed in the 20s were produced in the 30s, the one carrying on unchanged being the Ⅷ C.

Mark Ⅻ C engine

A Ⅻ C came onto the market in 1932 and this was a new engine. It had a bore and stroke of 53mm×67mm giving a capacity of 148cc. A cast iron deflector type piston with a floating gudgeon pin and an inertia ring was used, twin exhaust ports and an inlet manifold which could be had in a number of different styles to suit the needs of various users and a roller bearing big end with phosphor bronze main bearings was employed. Lubrication was by petroil and special ducts cast in the crankcase walls led the lubrication to the bearings. The ⅩⅤ C, introduced in 1934 was very similar but only had a single exhaust port. The Ⅻ C was prefixed GY and GYF, the ⅩⅤ C was CUX and CUXF. These engines were used to produce machines which qualified for low road taxes in most European countries, gave reasonable speed and power, and were very economical. The Ⅷ C was claimed to give 130 to 140mpg, the Ⅻ C similar but was 10mph quicker. The 1E, 2E and 196cc Super Sports supplied the needs for 200cc class machines until 1938 when the 3E was introduced to replace the 1E. The bore and stroke were now 59mm×72mm giving a capacity of 197cc, and were to stay at this for the rest of Villiers’s time as an independent company. The 3E and the 9D started a trend which was to follow for many years, both were made to a very similar pattern. A 3 speed gearbox was built in unit with the engine. It had a flat topped piston, 4 transfer ports, a single plate cork clutch and an endless roller chain primary drive enclosed in an oil-bath chaincase.

The 250cc class changed from the Ⅸ A and the Ⅹ A of 1930–32 (prefix JZ) to the ⅩⅣ A, ⅩⅥ A and ⅩⅦ A to the ⅩⅧ A.

The ⅩⅥ A was the last of the 247cc engines, it was made for use as a utility engine and became very popular. It had a separate cylinder head which was held on by only three bolts, two exhaust stubs and petroil lubrication, and otherwise follows the pattern of the Ⅹ A.

The ⅩⅣ A was a 249cc engine with a bore and stroke of 63mm×80mm giving a long stroke engine which was claimed to reach 60mph, and had strong pulling power at low speeds. It was available as an air cooled unit with petroloil (BYP), air cooled with autolube (BY), and water cooled with autolube or petroloil (RY).

All had detachable heads, a deflector topped piston fitted with inertia ring and either fixed or variable ignition. An outside flywheel was fitted to some models. They were made from 1934 to 1940.

Air-cooled and water-cooled Mark ⅩⅣ A

engines

The 350 class also went into long stroke engines with the introduction of the ⅩⅣ B in 1931. The bore and stroke were 70mm×90mm, an alloy head, was fitted alloy piston with inertia ring, detachable inlet manifold and a four pole magneto. An exterior flywheel was fitted. Autolube was used (prefix YZ) and a petroil model offered as an alternative (YZP). These engines were used by a number of firms to produce a lightweight combination at very reasonable prices.

The carburettor and flywheel magneto were both further developed during the decade, the carburettor through Marks I, Ⅱ and Ⅲ, the magneto from 2 pole through 4 and onto a 6 pole unit. On some engines 3 and 5 pole ones were used. Some builders made up their own ignition and charging systems by using a separate dynamo or ignition unit.

For the early days of the war Villiers continued to supply many motor cycle builders with their engines. They, along with many other engineering firms, had been approached in the pre-war period by the government to see what items they would be able to make should war come about, and in the early days they were given a contract to make shell fuses. They still continued to make engines for their normal customers where required.

This war work was to be developed greatly through the years with an increasing labour force and additional factory space which eventually grew from the pre-war 11½ acres to over 17 acres. To train the new staff employed, who were mostly women with no previous experience of engineering, and, in many cases, no experience of factory working, a training school was established. The items produced included, in addition to fuses of various types, primers, grenades, shells, castings in various metals for engines, bombs, mines, aircraft engines and vehicles as well as flywheel magnetos for rescue dinghies. Industrial engines were in demand from many pre-war customers and, in addition by various governmental departments. They were used to power generators in many different situations, powering water pumps used in fighting the fires created on the home front by bombing raids and by the Armed Forces to both remove water and to provide it in many overseas areas. One story indicates how Villiers were prepared to ‘Provide the tools to finish the job’ to quote Winston Churchill. An engine was needed to replace an American import which was now not available. Villiers were approached and asked to design a four stroke engine to do this work. Their design room staff produced the plans, the tool room the equipment and the new engine was produced in a record time. Further new both two and four stroke units were made as required motor cycle engines were produced for those still requiring them up to 1940/41 and development work was carried on. The only new motor cycles available to the home market after 1941 were autocycles and these were only available if a permit was granted. Those permitted to buy them were in work where public transport could not be used and were mostly either district nurses or those on war work who needed to be constantly available.

Villiers at war!

The James ML in use

When the Forces were supplied with motor cycles for use in airborne actions Villiers engines were used both in the Excelsior Welbike and the James ML paratrooper’s machine the ‘Clockwork Mouse’. The Royal Enfield ‘Flying Flea’ was fitted with a Villiers carburettor so again they played their part.

Many of those who had to lay their cars and motor cycles up when petrol rationing ended used cycles and as Villiers had become the largest supplier of freewheels this side of their work continued. As I said, they were still developing their engines and the 98cc Junior De Luxe and the 122cc 9D both had improved internal sealing provided during the war. These improved engines can be recognised by a change in the prefix from XX to XXA in the case of the JDL and a suffix A in the case of the 9D (to AAA-A) These engines are dated usually from 1941 but some of the earlier type engines were still supplied for a while yet.[Note 6]

The end of the war brought demands from returning servicemen, those who had stayed at home and those who in the 6 years of war had become old enough to have a driving licence, for new machines and for parts to repair older models. The whole industry had to reorganise itself, those who had been supplying the government with motor cycles mostly gave their war models a different colour paint and thus were able to give their dealers a few models to sell. Villiers were able to supply some JDL and 9D engines but the contracts they had with the government had to be completed so there was some delay in getting back to full production. A further problem was a shortage of materials as supplies of metal were rationed for some years. The metal and other materials needed for export sales was supplied but the material needed for home market production was severely restricted. 1946 saw the first new engine, a replacement of the 3E by the 5E. This was of a similar pattern to the 3E but instead of being a unit construction engine it now had the gearbox bolted onto the crankcase by four long bolts. This was a pattern which was followed by many of the post-war engines and, at a later date, enabled variations of 3 and 4 speed boxes with ratios suitable for road, scrambles, trials and road racing to be offered with some engines. Foot change was also included on the 5E.

Sectional view of the Junior de Luxe engine

The death of the founder of Villiers, Sir Charles Marston on the 21st May 1946 was a sad blow to all members of the firm. He had been Chairman of Directors since 1919. Like his father, John, Charles had, in addition to his work with Villiers, been a figure of the community. His interests had been varied, he had been a prominent member of the Conservative Party serving it in local, county and national spheres. He was a prominent churchman, and had led some, and supported many other, expeditions, both in the United Kingdom and the Middle East searching for religious artefacts. He had been created a Knight of St John, was a JP and had been elected to Fellowship of the Society of Antiquaries. He had written a large number of books and pamphlets emphasising these matters.

The decade was to see the death of another important member of the Senior Management Team, Frank Pountney, on the 30th August 1948. Frank had, of course, developed the flywheel magneto and developed and patented the Villiers cycle freewheel which was now used on the vast majority of bicycles. The style of letter prefix used on the engines was changed in 1947 when, instead of a letter itself, often including a number for each type of engine, the introduction of a number which indicated the firm the engine had been supplied to was substituted. Unfortunately some complications were built into this new system from the start when some numbers were used for batches of engines which were supplied to a number of machine builders. The best guide to these numbers that I have been able to find is that given by Roy Bacon in his book "Villiers Singles & Twins" in which he spends a total of over 17 pages on the matter. Even then he admits that the listing is not complete. It does not cover scooter and three wheeler engines and the numbers given to some builders do not start until some years after the change was made. Numbers reached the end of the 900s in 1951 and an A was introduced (036A was a 10D engine supplied to DMW), B came in 1956 when 013B was a 9E supplied to Ambassador, D in 1960 when 016D was a 33A supplied to Cotton, 15E in 1963 when 004E was a 9E supplied to Cotton and F started in 1966 and was mostly used on Starmaker engines. For some reason C was not used in this sequence.

The 2F engine

The 1F engine

In 1949 came further changes to the D and E ranges as well as two new engines to meet the requirements of those needing a 98cc engine, the 1F and 2F. The two 98cc engines were the same except for the fact that the 1F had a two speed fitting while the 2F, being intended for use in autocycles, had only a single speed with a clutch built into it. The 1F gearchange was operated by a handlebar control.

The engine had a bore and stroke of 47mm×50mm. The cylinder had two transfer ports and a single exhaust port. An alloy detachable head and flat topped piston was used and the main shaft was mounted on ball bearings with the big end roller bearings. The enclosed primary chain led to a 2 plate clutch. On the 1F the gear ratios were 1.54: 1 and 1:1. The 5E was replaced by the 6E which had the standard 59mm×72mm bore and stroke to give a 197cc capacity and was fitted with ball bearing main bearings. The choice of either a direct lighting system or a rectified system was available for lighting and flywheel ignition used as normal. The gearbox, bolted onto the engine as was the 5E gave a ratio of 1:1, 1.4:1 and 2.66:1.

The 10D again kept to the pattern set by its predecessor but was given a foot change. Before long an alternative ratio of gears was offered for use in competition work. The standard ratios were 3.25:1, 1.7:1 and 1:1, the alternative: 2.66:1, 1.4:1 and 1:1. Direct or rectified lighting were available to choice. A number of firms used the engine for trials and competition models, often offering tuned engines at an extra charge.

The 10D engine

The 1950s were to see the most prolific development period of the Villiers Company’s life. It started with the consolidation of the work of the late forties to see the 6E and 10D engines as well as the F series used in a great many builders machines. Developments in all of them went ahead. As they were all developed into a number of models I will deal with each one in turn.

The 6F engine

Firstly the 98cc F engines: autocycles, the only machines which used the 2F engines, were being demanded less and less so there was no change in the 2F, which was withdrawn in 1958. There was,. however, a demand for 98cc engines for use in lightweight motor cycles and scooters. The 1F was replaced by the 4F in 1953. The hand change handlebar control was retained but the ignition was improved and the contact breaker placed at the left hand end of the crankshaft where it was enclosed in an alloy cover giving it a neater appearance. A foot change model, the 6F, was introduced in 1956 with a hand change option retained. The final engine was the 9F, introduced in 1959, it was a tuned engine specifically designed for go-kart racing with a compression ratio of 9.15:1 as against the 8.0:1 of the 4F and 6F engines, tuned ports, and an S19 carburettor instead of the S12 fitted to the 4F and 6F. It was reported to have given good results. All the three latter engines are interchangeable.

The 122cc 10D model was proving to be a success in road models but there was a demand from riders competing in sporting events for something with an improved performance, so Villiers introduced the 11D. This had tuned ports, a larger carburettor and an improved flywheel in which more powerful magnets were used to give a stronger spark.

The 13D engine

A choice of three or four speed gearboxes was offered as on the 10D. The 4 speed option was signified by a D suffix to the engine number. The 12D replaced the 10D. It was a standard engine and was only available with a three speed box, as was the 13D, which was a combination of the 10D cylinder onto a 12D crankcase.

An important notation appears in most D and E Spares lists. It emphasises Villiers’s willingness to modify their engines to suit a customer’s need and had been the policy of the company for many years. It says "Alternative specifications are made for manufacturers’ individual requirements and the components fitted are designated below". The listing includes a special cylinder head, a separate inlet manifold and inlet manifold straight and a finned exhaust pipe nut for the 11D (comp) engine and a long list of parts for 7E and 8E engines.

The 6E engine was replaced in 1953 by two engines: the 7E and the 8E. The 7E was developed as a trials engine. It offered high compression pistons which gave from 8.25:1 to 10:1 as required and could be had with a 3 or a 4 speed gearbox option. The E had a big end with 16 separate rollers and used at first an S24 and then an S25 carburettor. The 4 speed box used a different primary chaincase to house the primary drive chain and a stronger clutch assembly. Both standard and wide ratio boxes were available. They were quickly accepted by many firms and, as well as in road machines, both the 7E and 8E were used in many sporting activities and in three wheelers and scooters. The use of the 8E in three wheelers encouraged Villiers to introduce the availability of both self starting and a reverse gearing in 1954. As with the D range, stronger magnets and coils were available for engines used in sporting activities and these were also available for use in three wheelers where they gave a better lighting system. A choice of either direct lighting or rectified lighting systems was available on the D and E engines.

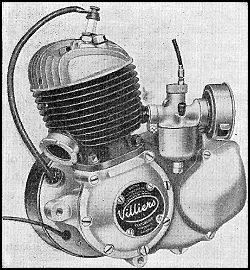

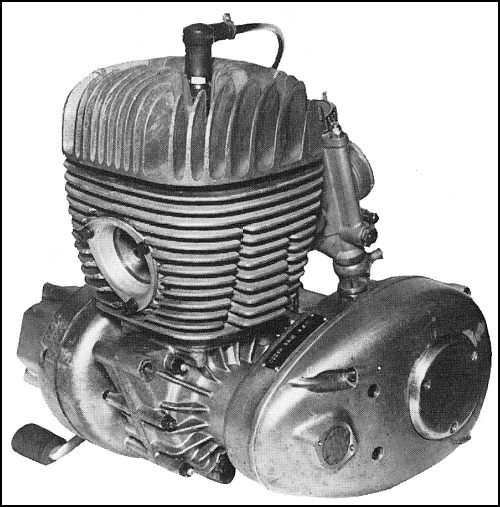

The 9E engine

In 1955 the Mark 9E engine was offered. This had a smoother outer appearance and was used as a pattern for future developments. It was made available in either sports or trials trim, the trials model having a heavier flywheel to give smoother torque at low speeds. A compression ratio of 8.25:1 was used, a caged roller bearing big end with 9 steel rollers and a special ignition coil with a cam which gave a longer dwell in the closing of the contact breaker points. Trials engines were fitted with a gearbox giving wide ratios and the sports, or scrambles engine standard ones. A number of different specifications were offered for kart engines and a standard model fitted with turbo cooling fan and a choice of either kickstart or electric start for use in scooters was also available. The electric starter used in Villiers engines was the Siba Dynastart which used a 12-volt system. The reverse mechanism used the fact that a two stroke engine runs just as efficiently in reverse as forward and fitted a switch which stopped the engine and then restarted it in reverse. Engines fitted with electric starter, fan cooling and reverse gears are noted by the additions of S, F and R after the Mark coding e.g. 9E/3SFR is a 9E engine fitted with a 3 speed gear, a starter, fan cooling and reverse gear.

The 10E, which had a cylinder in an upright position and the 11E, which was a slimmer version for use in scooters were both introduced in the latter years of the decade. The 9E was produced until 1967, the last year of Villiers as an independent company. It had certainly been a success. 12 years production in its own form and the last of a series first introduced in 1928, 39 years production with only the war years forcing a stoppage.

The 1H engine

A new introduction in 1954 was the 1H, an engine of 224cc. The bore & stroke were 63mm×72mm. Its compression ratio was 7.5:1 and had a 4 speed gearbox with ratios of 1:1, 1.32:1, 1.9:1 and 3.06:1. The S25/5 carburettor was enclosed by a cover which incorporated the air filter. Modifications were made to the primary drive, a tensioner was dropped and a felt washer was replaced by a rubber seal on the chaincase. In 1957 it was replaced by the 2H which had a bore and stroke of 66mm×72mm giving a 248cc capacity but was otherwise a similar engine. Both engines were used in bikes and scooters and are highly spoken of.

1954 also saw the reintroduction of a 150cc class engine. The 8C had been dropped in 1947. The new engines were both of 147cc: the 29C and 30C. Their bore and stroke were 55mm×62mm, a roller bearing big end was fitted and the crankshaft was carried on 3 journal ball bearings. The 29C had tuned porting and a competition type magneto with a larger S25 carburettor and a four speed gearbox of 1:1, 1.35:1, 1.8:1 and 2.93:1 for the standard gear ratios coded S, a wide ratio box coded V gave ratios of 1:1, 1.35:1, 2.3:1 and 3.47:1 while the 30C had an S19 carburettor. Direct or rectified lighting systems were available on both engines.

The 2T engine

The 29C was replaced by the 31C in 1956. This had a bore and stroke of 57mm×58mm giving a capacity of 148cc. A choice of 3 or 4 speed boxes was available and variations included fan cooling with either kickstart or self starter for scooter use. The 30C was dropped in 1959 and the 31C in 1964.

An introduction which excited many interests in 1956 was that of a new twin engine, the 2T. The vertical twin had a bore and stroke of 50mm×63.5mm giving 249cc. Each barrel had its own crankshaft, separated by a central disc in the crankcase holding a central bearing with a roller bearing on the magneto side and a ball bearing on the sprocket side. The small ends are steel backed brass bushes. Alloy heads were fitted to the cast iron cylinders. The compression ratio was 8.2:1 and a choice of standard or wide ratio boxes with 4 speeds were offered. Starter, reverse and fan options were available.

A 3T with the bore widened to 57mm to give 324cc capacity was introduced in 1957 and a 4T in the 60s. The 3T ran until 1964, the 2T until 1968. The 2T was widely accepted and was almost immediately a star feature in most customers’ catalogues. They became very popular machines giving good acceleration and a high maximum speed in the mid 70s. They are still one of the most sought after post-war road models.

The 3K engine

Another new engine brought back a 175 unit. The Mark 2L was made to the same pattern as the 9E with a bore and stroke of 59mm×63.5mm giving a 173cc capacity. It had a compression ration of 7.4:1 and a choice of 3 or 4 speed gearboxes and kick or electric start and fan cooling if required. In 1956 the A class came back with the 3lA. This was intended for use in three wheelers but was quickly adapted to become a trials motor. The 33A was then produced as a scrambles engine. Again they followed the pattern of the 9E. The 66mm×72mm bore and stroke gave 246cc and both had four speed gear ratios fitted. Wide ratios on the 31A, standard ones on the 33A. The 31A had a compression ratio of 7.4:1 and the 33A 7.9:1. For scooter and three wheeler use starter and reverse were offered. The last new engine of the 50s was a new venture for Villiers: a moped unit. Named the 3K, it was a 50cc engine with built in clutch and two speed gearing as the 1F had been. It had a 40mm×39.7mm bore & stroke, a compression ratio of 7:1 and used an SM10 carburettor. Pedals were built into the unit. It included a bushed small end and a roller bearing big end with ball bearings supporting the crankshaft. It was used by a small number of firms but the demand for mopeds was falling and it was only produced for two years.

Villiers had been expanding during the 50s both by building a new factory in Australia and by the purchase of a number of firms. The most important of these to motorcyclists was J A Prestwich in 1957. JAP and Villiers engines had been in competition for small and medium capacity machines for many years and they had both developed important markets for their industrial engines. It was a sad day for many, although JAP engines had only been available as speedway and grass track engines for some time. The Villiers workforce was now over 2,000 strong and their factory area in Wolverhampton alone exceeded 20 acres. Included in the JAP organisation was Pencils Ltd who were making over 40 million pencils a year! 1959 was the 60th anniversary of the foundation of the Villiers Company and, to celebrate it they produced a small handbook; in it they list 312 users of their engines and a total of 87 different products they could be found in.

Engines were still being developed in the sixties, the A series was the greatest beneficiary in this period. The 32A was developed as a trials engine, the 33A became the 34A, still a scrambles unit and the 35A was supplied to Bond for use in their three wheelers. The 36A was very similar to the 33A and 34A engines. A wide range of 4 speed gearbox variations were available and, a new departure, Villiers offered the 33A, 34A and 36A with Amal carburettors. An Amal 389/39 was fitted to them. Villiers S25/5 carburettors were used on the 32A and 35A engines. Compression ratios were 7.4:l on the 35A, 7.9:1 on the 32A and 12:1 on the 34A and 36A engines.

The final development of these engines was announced in 1965 when the 37A came on the scene. This had many of the features of the 32A but used a lightweight crankshaft, gearbox shell and end cover and was fitted with a special wide ratio gear cluster. As these A engines were similar they could be changed for events as required by the rider and they were well used in events in many parts of the world. I will comment upon results later.

The 3L, already mentioned in Part 5 was introduced in 1960 and the 4T in 1963. This was very similar to the 2T, giving 249cc capacity but was given a higher compression ratio of 8.75:1 as against the 8.2:1 of the earlier units. Three variations were offered, the 4T for use in motor cycles and the 4T/SK and 4T/SKR for use in scooters and three wheelers. The 4T had an 18 tooth final sprocket and the others a 17 tooth sprocket. All used the Villiers S25 carburettor. They were recorded as giving over 17 brake horse power at 6,000rpm. The 4T used a Villiers flywheel magneto and the others had a Syba Dynastart fitted.

The engine I have left to be the last I detail is one that made some enthusiasts think that Villiers had taken on a new lease of life. They named it Star Maker (later changed to Starmaker). It was designed by Bernard Hooper and was originally intended to be for use in scrambles but was soon being used as a road racing engine. Various firms and individuals were adding their own tuning and Villiers, as always, took note of this and soon there were three variations available, a road racer and a trials unit in addition to the scrambles engine. The engine prefix indicates the variations offered on the engine and includes 757D for the standard scrambles engine, 490E for a road racing version, 834E a road racing engine with closer finning on the barrel and head, 871E a trials engine, 972E a standard road use engine fitted with 12-volt rectified lighting, 131F a trials engine with 6-volt direct lighting. The Starmaker engine had a bore and stroke of 68mm×68mm giving a capacity of 247cc. The compression ratio was varied, the road racer having 13:1, the scrambler 12:1 and the trials engine 8:1. Different gear ratios were used on each, road racer 2.21:1, 1.45:1, 1.2:1 and 1:1, scrambler 2.52:1, 1.66:1, 1.255:1 and 1:1, trials 3.5:1; 2.08:1; 1.375:1; and 1:1, and different carburettors and inlets were used: racer Amal 3 GP2 with a 1.5 inch choke, scrambler Amal 389 monoblock with a 1.375 inch choke, trials Villiers type S25 with a 1 inch choke.

Road racing Starmaker engine

The cylinder is fitted with a cast-in austentite iron liner which has equal expansion rates to the aluminium cylinder, the trials and scrambles engines have wide pitched finning to prevent mud clogging them up while the racing cylinder has close pitched finning with angled fins on the head to direct air to the sparking plug A full circle crank was used on racing and scrambles engines to help preserve the high compression and on all engines the forged steel connecting rod fitted on a caged needle roller big end, roller bearings supporting it. The magneto was an energy transfer unit. Trials engines could be had with 6- or 12-volt systems. The racing engine in supplied form gave over 31bhp at 7,400rpm, the scrambler 22bhp at 5,500rpm and the trials engine 14bhp at 5,500rpm. Tuners increased these figures.

Bill Ivy on a Cotton Starmaker rode at many events in all parts of Great Britain and often showed all other machines the way home. And similar success was gained by other riders in all manner of events but the occasion when many motorcyclists were encouraged to believe that the time would not be too far distant when once again British machines and riders would be at the top of the world road racing tree once again was when in 1966 Villiers entered a machine which had a Starmaker engine in a Bultaco frame and was ridden by Peter Inchley in the 250cc Lightweight Class in the IOM TT. It came in third, the best British result in this class for many years. Unfortunately it was not to be, but that part of my story follows later.

The 60s saw the end of Villiers as an independent supplier of motor cycle engines. It possibly started with the retirement of Prank Farrar from the post of Chairman of the Company in 1957. He was succeeded by his son, Leslie and when he retired in 1965, Manganese Bronze, who had been buying shares and then owned 20% of them made an offer for the rest. When this was accepted they combined Villiers with the Norton AMC company they owned and soon afterwards formed a new combine: Norton Villiers Triumph. NVT, as it was known, announced that they would supply no more Villiers engines to other motor cycle builders but would be fitting them into their AJS bikes. They produced some 250cc machines but it was left to Fluff Brown, who continued to build them after NVT closed down to do further work on the Starmaker and enlarged the engine producing models with 350 and 358cc engines to produce a scrambler which at first gave a good account of itself.

The results gained by machines powered by Villiers engines during the 60s were too numerous to list in detail. In many trials there were well over 50% of entrants riding them. In the results these figures were otten exceeded because so many of the top riders were on works machines from firms using them.

To just mention a few, and can I apologise to any reader who does not find his or her own achievements listed? As an example, in February 1964 in 90 trials results listed there were 1,215 awards made. Of these Villiers engined machines gained 707—some 60%.

During the decade, in addition to the road racing successes already mentioned, Dave Bickers won many awards in scrambles and moto cross events both in Great Britain and Europe, including the 250cc class of the Belgian Moto Cross Grand Prix on his Greeves Villiers. D Mc Bride won the Irish Experts Trial and Mick Andrews the Northern Experts on a James Villiers 246 machine. The Greeves works team, all Villiers engined, won the 1967 Team award in the Scottish Six Days. The biggest triumph in the Scottish Six Days must be granted to Bill Wilkinson who, in 1969 took the Premier Award on a 246cc engined Greeves Villiers machine. This was the last time it was won by a British rider on a British built machine and until British machines for use in such events become available again that will be the last time it was done. There were many more wins, I am only able to list a few as to try and list them all would fill more space than this whole issue.

The Villiers name was bought and a new company moved into the old Marston Road factory and produced industrial engines. They prospered and the last I heard from them they were building a new factory in South Africa to meet the increasing demands from that area. I have tried to contact them again recently but have had no response and a visitor to Marston Road, where he used to work, informed me in January that the last time he was there the factory was being demolished. It is a pity that they could not have left it so that the Centenary of the Company could have been celebrated there in 1998.

This was first published as a series of articles in The Independent—the magazine of the British Two Stroke Club—during 1999.

Villiers Junior prototype