Issue 5 (February 2004)

The Ghosts & Scholars M.R. James Newsletter is published two or three times a year at irregular intervals. Click here for further information on how to buy the full hard-copy edition. Contributions are welcome - click here for Guidelines.

Editor: Rosemary Pardoe (e-mail); Assistant Editors: David Rowlands and Steve Duffy.

Copyright © 2004 Rosemary Pardoe. All rights retained by the contributors. All unassigned material by Rosemary Pardoe. Not to be reproduced without the permission of the authors/artists.

Contents

"News"

"The Treasure of Steinfeld Abbey: A Visit to the Scene of 'The Treasure of Abbot Thomas'" by Helen Grant

"The MRJ Price Index" by Don Tumasonis

"Jamesian Notes & Queries" ("Was Ann Clark Pregnant?" by Tina Rath; "Hostanes Magus" by Rosemary Pardoe; "M.R. James and Sex" by Muriel Smith; "Spiders in 'The Ash-Tree'" by Jacqueline Simpson; "The Second Boyhood of Dr James" by David Longhorn; "Follow-ups (Author Connections): George MacDonald, Robert Graves")

"Reviews" (The Haunted Baronet and Others: Ghost Stories 1861-70 by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu; Afternoon Play: The House at World's End by Stephen Sheridan)

"Letters"

Artwork: Alan Hunter ("A Neighbour's Landmark"). Douglas Walters (web site edition only: A figure in St Michan's Church, Dublin; ref. "Lost Hearts"). Douglas Walters ("The Treasure of Abbot Thomas"). Steinfeld Photographs by William Bond.

2004 is the centenary of the publication of M.R. James's first ghost story collection, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary. The G&S Newsletter is marking this occasion in typically perverse fashion with a special supplementary booklet which has almost no connection at all with GSofA! Number 5 of the Newsletter is smaller than recent issues because of this accompanying publication: MRJ's previously-unpublished Occult Sciences. I'll let the booklet speak for and explain itself, but I hope you share my excitement over it (for more information, click here). There may well be future special booklets of a similar sort included on Newsletter subs - not necessarily every year but hopefully often enough to give added incentive to people to keep subscribing (Occult Sciences is also available to non-subscribers, but at a price only a couple of £s less than a full year's Newsletter subscription).

As for the Newsletter itself, on top of the satisfyingly bumper crop of short articles in "Jamesian Notes & Queries", the main article in this issue follows from my suggestion in issue 4 that people might like to contribute "Jamesian Traveller" articles covering the locations of MRJ's stories. Helen Grant has come up with a fine piece on Steinfeld Abbey ("The Treasure of Abbot Thomas") to set the ball rolling. On file, in preparation or in the planning stages for the future are pieces on Aswarby ("Lost Hearts"), Wilsthorpe ("Mr Humphreys and His Inheritance") and the Kilpeck area ("A View from a Hill"). If you have ideas for others or are looking for possibilities in your part of the country/world, please contact me. Is there anyone, for instance, who would like to tackle Cerne Abbas ("An Evening's Entertainment")?

Finally, my thanks to all of you who sent good wishes and get well cards after my accident in August last year. Despite a lengthy recovery period, it hasn't interfered with the Newsletter schedule, but this was only because it happened at a 'good' time, just after Newsletter 4 appeared. This has made me dubious about taking on the responsibility of a formal M.R. James Society, so it looks as though the Newsletter will stay as it is for now.

The name of Steinfeld Abbey is well-known to M.R. James enthusiasts as the scene of James's intriguing tale "The Treasure of Abbot Thomas". The story was inspired by the stained glass windows of Steinfeld, which James inventoried in 1904 for Lord Brownlow at Ashridge Park (Hertfordshire). His connection with the windows is well-documented, and many of them are now owned by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.[1] However, information about Steinfeld Abbey itself is much less accessible; Steinfeld is off the beaten track and most of the information available is in German.

I and my family moved to the Eifel in 2001 and found ourselves living only ten miles from Steinfeld. As a German speaker with a love of the stories of M.R. James, I was in the fortunate position of being close enough to visit Steinfeld Abbey to see for myself the scene of Mr Somerton's ill-fated search for the treasure of Abbot Thomas von Eschenhausen. I would like to take you with me now as I retrace the steps which led me to the true treasures of Steinfeld.[2]

"Die schöne Eifel" - "The beautiful Eifel" - has a reputation for beauty of an exceedingly rustic nature. The northern Eifel, where Steinfeld is located, has a rolling landscape with extensive forests populated with deer; red kites and other birds of prey circle overhead. In winter, temperatures drop as low as minus seventeen and smaller roads are blocked with snow. Many people still live in houses made of fachwerk (a type of half-timbering) which they decorate with stag's skulls and antlers, and sometimes with murals of rural or religious scenes. Longer-term inhabitants of the area speak Eifelplatt, a dialect well-nigh incomprehensible to outsiders.

The area is rich in legends and tradition. In the forest bordering the mediaeval town of Bad Münstereifel, an impious huntsman is condemned to roam endlessly with his hounds. There is also the story of the terrifying "Fiery Man of Hirnberg" who burns with a blazing light.

Steinfeld itself is situated approximately 520 metres above sea level on a hilltop where the climate can be euphemistically described as autumnal. The Premonstratensian order (who controlled Steinfeld Abbey for much of its history) favoured hilltops for their settlements. Steinfeld can still best be termed a village, as it was by Mr Somerton's valet William Brown, rather than a town. There is one main road running through it but no rail connection, the nearest being in the neighbouring town of Urft. In 1859, the date of Mr Somerton's adventure, the Cologne-Trier highway had only recently been built (in the 1840s); the railway line via Mechernich and Kall was yet to be laid, in the 1860s. Steinfeld, which still retains an out-of-the-way feel today, must have felt extremely remote in those days.

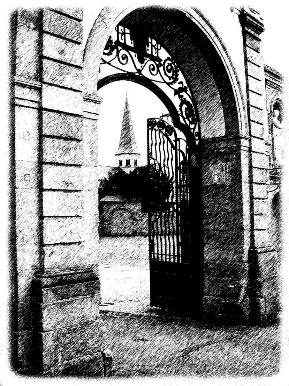

Most visitors to Steinfeld are likely to approach via Urft from one of the larger towns of Kall or Mechernich. The road from Urft winds uphill through open countryside bordered with trees to the hilltop where the Abbey stands. The first views of the Abbey and its surrounding buildings are the sharp spire of the Abbey church, tiled in blue slate, and the twin towers at the west end of the church. These rise above a wall between twelve and fifteen feet high (completed in 1789) which runs around the entire Abbey grounds. In autumn the trees which overhang the wall are heavily laden with apples and horse chestnuts, apparently undisturbed by the depredations of local children.

Following the wall along its south side one comes to the main entrance, a fairly modest archway with iron gates. Through these, one enters the large "chestnut courtyard", now somewhat prosaically used as a carpark, and also containing the Abbey bookshop. There is a well in the courtyard, but of relatively modern construction and plain design, with the roof tiled in slate. There is a second well at Steinfeld, of which more later. Standing with one's back to the gateway, one can look directly ahead towards a broad three-storied building, again with a slate roof and with the walls covered by a yellowish facing. In the centre is a passageway leading through into a second courtyard. The Abbey church lies to the right. Passing through the passageway into the second courtyard, one can either turn right to approach the group of buildings surrounding the cloister, or go straight ahead to the end of the courtyard, where one turns right into a smaller "working" yard. The visible architecture is a mixture of Romanesque, Baroque and nineteenth-century work. All of this is now in a good state of repair, the Abbey having been a Salvatorian monastery since 1923. The Salvatorians have further added a high school and boarding school to the west of the Abbey complex. In order to imagine what the Abbey must have been like in Abbot Thomas' time - the 1520s - and subsequently in the 1850s when Mr Somerton is supposed to have made his visit, one must look much more closely into both its architecture and its history.

There have been monastic settlements at Steinfeld since the time of Henry I in the 900s AD. The Premonstratensian order, founded by St Norbert of Xanten, later bishop of Magdeburg, took over the site in the 1100s and in 1184 it became an Abbey. An unbroken succession of 44 Abbots held sway until dissolution in 1802. There was no Abbot Thomas von Eschenhausen, although some of the names, listed upon a painted wooden panel on the north wall of the Abbey church, have a similar resonance: Abbot Johann VI Schuys of Ahrweiler (1517-1538); Abbot Simon Diepenbach von Hasselt (1538-1540); Abbot Jakob II von Panhausen (1540-1582).

The church itself was built in 1142-1150 in the Romanesque style and is dedicated to St Potentinus and his sons. However, the two imposing towers at the west end are a very much later addition. The original west facade was very simple and it was not until the Baroque period that side towers were added. There was a roof fire in 1884, after which the west front was redesigned by the Cologne architect Weithase, with the two steep towers which one now sees. These would not therefore have been extant in their current form at the time of Mr Somerton's visit.

More serious for the historical veracity of M.R. James's story is the fact that there is no "great window at the east end of the south aisle of the church." The church windows are all relatively small and plain ones. The magnificent glass which James saw at Ashridge Park in fact came from the cloister at the north side of the church. Here, however, fiction and reality do converge, as the cloister was built and the windows installed at the time of the putative Abbot Thomas. The construction of the cloister began in 1499 under Abbot Johann IV of Düren and was completed by Abbot Godfrey II of Kessel (1509-1517) and his successor Abbot Johann VI. Abbot Johann began the installation of the windows in 1526 (three years before Abbot Thomas is supposed to have "died rather suddenly in the seventy-second year of his age") and the last was installed in 1557.

The fate of the cloister windows was much as it is described in James's story. They were removed and replaced five times during periods of war and unrest; in 1785 Abbot Felix Adenau had them packed up for storage, perhaps also for safekeeping, perhaps because they had become damaged as a result of being removed and re-installed so many times, and perhaps also to allow the damp cloister to dry out. They subsequently disappeared from the monastery. In 1802, secularisation brought to an end the line of Abbots dating back through centuries, and the windows are thought to have been sold off in England through the agency of John Christopher Hampp, a German living in Norwich. The loss of the windows is a cause of great sorrow to the current inhabitants of Steinfeld: "What if John Christopher Hampp had never travelled?" wails a headline in their exhibition about the glass, situated in the plundered cloister. For over a century the glass was completely lost as far as Steinfeld was concerned. It was not until the beginning of the twentieth century that it re-entered Steinfeld's history, through the agency of M.R. James.

The glass which MRJ inventoried for Lord Brownlow in 1904 was, as it turns out, not all from Steinfeld, though a good proportion was; and it is certainly the biggest and best-preserved collection of Steinfeld glass now extant (other sections have since been located in English churches). It was the inscription "Abbas Steinfeldensis" on one section which alerted James to the provenance of the glass and inspired the location of "The Treasure of Abbot Thomas" at Steinfeld.

And what of Job, John and Zechariah? Do the fictional figures conform with actual scenes in the Steinfeld glass? The subject-matter of the Steinfeld stained glass was an impressive cycle of pictures depicting Freedom of Choice, Redemption and Judgement. The main pictures in the first window showed the Fallen Angels and Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. The Life of Christ was also depicted up to the Crucifixion, Resurrection and Ascension, followed by the Pentecost, the Crowning of Mary and finally the overcoming of Beelzebub and Lucifer in the last window. In the tracery windows were scenes from the Old Testament, and in the base sections were saints, canons and monks. Not all have been located, or perhaps even survive, but the themes were catalogued in detail twice, in 1632 by Johannes Latz, and again in 1719 by Heinrich Hochkirchen.

St. John - Johannes Evangelista - was included amongst the holy figures portrayed in the Steinfeld glass. The St John glass shows the saint on the island of Patmos writing the Apocalypse, and therefore holding a book or scroll of his writings as in MRJ's story. However, the picture came from the series of holy figures depicted in the base sections of the windows, and the figure itself is not large enough to have occupied a whole light. For those who would like to see it for themselves, this particular piece of glass is featured on the Steinfeld monastery website (http://www.kloster-steinfeld.de)[3] along with other scenes. These include St Simon holding a glass reliquary containing a severed arm. The St Simon glass is one of only two which have been returned to Steinfeld, and does not appear to have been part of the Ashridge Park collection ultimately inherited by the Victoria and Albert Museum; however, it is very reminiscent of the descriptions of the holy figures described in James's story, and as such is worth a look.

We turn now from the stained glass to the question of the courtyard and well where the treasure of Abbot Thomas was located. In the story, Mr Somerton is required to find the location of the Abbot's house and its courtyard himself. The Abbey church is surrounded by "a number of rather ruinous great buildings mostly of the seventeenth century." There is no set place in which the house should be located according to church custom, but he eventually identifies it in the "three-sided court south-east of the church, with deserted piles of building round it, and grass-grown pavement." The well is "a very remarkable thing" carved of Italian marble with Biblical reliefs, and has an arch over it with a wheel over which the rope would be passed.

Mr Somerton's visit in 1859 would have been made during the period of secularisation. At this time the Abbey church was still in use as a parish church, but many of the Abbey buildings were pressed into use for non-religious purposes and could well have been in a parlous state until the Salvatorians took over in the early twentieth century. The church and cloister remained from the 1500s, but all the other Abbey buildings are of a later date. Thus far fiction and fact agree. Abbot Norbertus Horrichem started work on new Abbey buildings in 1661, and in the 1700s the buildings surrounding the cloister were rebuilt from the foundations up. These included new apartments for the Abbot, built under Abbot Evermodus Claessen (1767-1784). But what of the Abbot's old living quarters?

Gaining access to the area south-east of Steinfeld Abbey church is not straightforward, as it seems to have been for Mr Somerton and William Brown. The towering ivy-covered wall which surrounds the Abbey makes it impossible to see anything of that part of the grounds from the road outside. In fact, as this wall was completed in the late 1700s it would also have stood there at the time of Mr Somerton's visit! A section of wall also extends from the encircling wall to the south side of the church, thus effectively shutting off all sight of the south-east part of the grounds. Walk around the outside of the wall and you can see nothing but the church spire and towers. Follow it anti-clockwise and it continues without a break until you are at the north-east side of the church. Here at last there is a set of gates, as forbiddingly high as the wall, and through them can be glimpsed an overgrown part of the Abbey gardens, with fir, beech and elderberry, and tall nettles. It is still not possible to see through the thick growth to the south-east side of the church. Nor is it possible to see anything of this area from inside the church, where the windows are too small and too high up to see through.

Having made this tour of the outside of the walls myself, it was at this point that I was obliged to approach the lay brothers in the Abbey bookshop and ask for help. I did so with some reluctance as I was not sure how well received I would be if I explained that I was essentially on a 'ghost hunt' in what is, after all, a devout Catholic community! However, my request was kindly received and it was arranged that one of the Salvatorian sisters should take myself and my companion into a private section of the grounds which includes the area south-east of the church.

I have to report that no "three-sided court", ruined or otherwise, lies to the south-east of the Abbey church. If anything of significance was sited there at the time of Abbot Thomas, no trace of it remains. Close in by the walls of the church is a modern graveyard for the Fathers, Brothers and Sisters of the Salvatorian order, with neat rows of plain stone crosses bearing only names and dates. A path runs along the outside of the graveyard, next to it a thick screen of bushes, and beyond that a stretch of garden at a lower level, bordered by the outside wall. If there ever was a pavement there, or indeed a well with or without a sinister occupant, the Salvatorian faithful now slumber undisturbed above it.

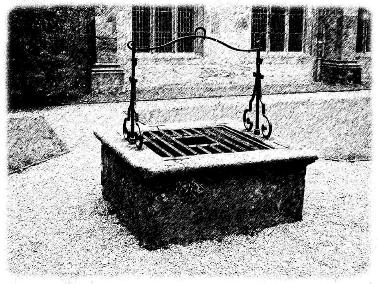

This is not, however, quite the end of the story. There is still the second Steinfeld well to visit - for indeed there is one. It lies in the centre of the cloister courtyard, which does of course date to the time of Abbot Thomas, the early sixteenth century. The Abbot's living quarters of the 1500s were in fact located close by at the west side of the cloister, although any traces were obliterated by the rebuilding in the 1700s. The cloister itself was notoriously damp, and the courtyard, reached via a wooden door on the north side, feels chilly and bleak. The Abbey buildings surrounding the cloister, which were rebuilt in the mid-1700s, overtop it by several storeys, casting shade on the courtyard. Underfoot is gravel, interspersed with small sections of lawn. In the centre is the well, with square well-head and ornamental ironwork. Look down the well and you will see dark water only a little way below you. If the well has any secrets to hide, they now lie far beneath the black surface of the water.

Before we leave Steinfeld Abbey, I would like to show you one more thing. In the west side of the cloister, within sight of the well-head, is the small exhibition about the lost Steinfeld glass. Alongside the story of the glass and photographs of some of the scenes depicted in it, is a paragraph about the "bekanntester englischer Geistergeschichtenschreiber",[4] M.R. James, who inventoried some of the Steinfeld glass in 1904 for Lord Brownlow and was inspired shortly afterwards to write "The Treasure of Abbot Thomas". Following publication of the story, it was mentioned in the newsletter of the Eifelverein (Eifel Club) in March 1907. The report was read by Father Nikola Reinartz of Kreuzweingarten, who subsequently contacted MRJ during a visit to England and saw the Steinfeld glass for himself. He was thrilled. "In Ashridge Chapel I feel as though a stroke of magic has transported me home to the Rhineland!" he exclaimed. After over a century of being lost, the whereabouts of the Steinfeld glass was at last made known again to the faithful of Steinfeld. The "English ghost-story writer" had indeed discovered the lost treasure of Steinfeld.

Notes:

[1] For more on the Ashridge glass and the MRJ connection, see Nicholas Connell, "A Haunting Vision: M.R. James and the Ashridge Stained Glass", Hertfordshire's Past 49 (Autumn 2000), pp.2-7.

[2] M.R. James himself, as he admits in the story, never visited Steinfeld.

[3] To view the stained glass on the Steinfeld website, click on the following: Kreuzgangfenster (left of home page); Weiter; Bilder der Kreuzgangfenster (right of page); Fensterauswahl (drop down box to select picture).

[4] "Best-known English ghost-story writer."

The photographs of Steinfeld below were taken by William Bond (© 2004).

---

---

George Martin, the villain of M.R. James's "Martin's Close", has no obvious reason for cutting Ann Clark's throat. He was angry that an advantageous match had been broken off because of his connection with the girl? Well, yes, but the murder took place some time after this disappointment: he had had time to get over it (and to appreciate, as the narrator points out, that it was no one's fault but his own). The girl continued to follow him and annoy him whenever he passed through the village? Again, yes, but sooner or later this would have stopped, or the business which kept him in the area would have come to an end. And although he certainly lashes out at the girl (literally, striking her with his whip), the actual murder is not a piece of sudden, unrestrained violence. It is planned. He is said to have "stopped and said some words to her with which she appeared wonderfully pleased, and so left her; and after that day she was nowhere to be found." The clear implication is that he has asked her to meet him, presumably beside the pond where he disposes of her body, with the intention of killing her. Why?

There is a hint in the earlier part of the narrative. Ann Clark would watch for him, and he would call to her: "it seems they had a signal arranged: he should whistle the tune that was played at the tavern" - the tune of "Madam, will you walk?" which plays such a sinister part in the later haunting. So George Martin would whistle the girl out to a rendezvous. (Or, according to the evidence of the little cow-boy, sometimes she would wait for him on the moor.) Would he take her to the pond? And then...? True, Ann Clark is described as "very uncomely in her appearance", with "a great face and hanging chops and a very bad colour like a puddock", but her ugliness would not necessarily be a protection against sexual exploitation. Abuse of those who are helpless to protest or protect themselves because of their mental state is by no means unknown, and George Martin, quite capable of casual cruelty to the helpless Ann, could well be capable of this as well. Otherwise, why does he continue to see her, actually calling her out as he passes? The joke, such as it is, of Ann believing she has found "so likely a sweetheart" must have worn out very quickly, but Martin keeps it up. Is it because he finds the girl is available, persuadable, incapable of complaining... why not take advantage... and surely, with such a sub-human creature there could be no risk of pregnancy? But if it turns out that there is (could some of Ann's "broken words" and her pathetic attempts to re-awaken his interest have carried hints which he could understand only too well?), then the scandal which led to the loss of his first bride will be nothing to what will erupt when Ann's condition becomes evident. (Her family are respectable, and they clearly value Ann - she goes with them to the dance, and they do not hesitate to protest about Martin's cruel joke. Might they demand that he marry her...?) The only possible way out is to kill her before her family realise what has happened.

There are all sorts of resonances in the text which suggest that the murder has a sexual motive: the title of the story "Martin's Close" itself suggests the notorious case of Maria Marten, also murdered, according to the melodramatic version of her story, by a "wicked Squire", who had seduced her; and whose body was discovered by supernatural intervention. In fact, the unfortunate Maria was a serial seducee, who had already had one child by another man, who was duly paying her maintenance, rather spoiling the picture of the ruined and deserted maiden; while William Corder, (possibly) her murderer, was a singularly ineffectual young man and not a moustache-twirling villain of popular legend. I cannot help feeling, too, that Mrs Marten should have been questioned much more closely on that dream which was alleged to have led to her demanding that her husband dig in the Red Barn to find their murdered daughter. It argues rather more knowledge of the crime than she should have had. She was not actually Maria's mother, either, but her very young stepmother (young enough to feel jealous and to resent Maria's serial misbehaviour and the way she seemed to be rewarded for it). But the popular image of Maria, the seduced girl murdered to prevent scandal, persists.[1]

Then, there are the circumstances of Ann Clark's murder. They suggest a familiar situation in English folk-song: a young man asks his sweetheart to go for a walk in the countryside, often beside a stream or a river. The girl, who is pregnant, asks when he is going to marry her, or perhaps simply remarks that her family will be angry if she should be "cast-away". The boy kills her, sometimes battering her head with a stake from the hedge, but often with a knife, and throws her body into the water. (Matters are complicated by the fact that there are often American versions of these songs, in which the girl is killed for no obvious reason - the young man apparently has a brain-storm - or because she refuses to marry him; but premarital pregnancy was not a subject that could be sung about in public in America.)

Ann Clark suffers the fate of "fair Susan":

Of the "Oxford Girl":

And of the unnamed girl from the song I quote at the beginning of this article, left lying stabbed by her lover "amongst the roses." Ann Clark is a more pathetic victim, because she is more helpless, "a poor innocent", but she is in the rural tradition.

Note:

[1] (Editor's Note) MRJ wrote about the Murder in the Red Barn in Suffolk and Norfolk (J.M. Dent & Sons, 1930), p.54: "Polstead was the scene of the Red Barn tragedy. In 1827 William Corder deceived and murdered Maria Marten and buried her in the Red Barn (not now extant), representing to her parents that he had taken her away to marry her, and that she was living in the Isle of Wight (or elsewhere). Her stepmother began after some months to dream that she was buried in the barn, and the father and brother made search and found the body. Corder meanwhile had married a respectable woman near London. He suffered at Bury. A play of the Red Barn long held the stage."

In "The Ash-Tree" MRJ exploits two of the best-known folk traditions about witches: their ability to transform into mysteriously uncatchable hares, and their ability to send their animal familiars to harm enemies. In the evidence given at witch trials, these familiars are described in many different ways, some realistic, some fantastic; in rural folklore of the nineteenth and early twentieth century they are either mice, toads, or occasionally cats. I had nowhere seen any mention of spiders as familiars, and so had supposed that in choosing this species as the witch's agents MRJ was influenced by his own arachnophobia, and perhaps by the convenience of spiders for his plot - they could plausibly both enter and leave an upstairs room by the window.

Now, however, I have accidentally come upon an item which must surely have been known to MRJ, since it concerns his own county of Suffolk, and which looks to me convincingly like a source for those witchy spiders. It is to be found in County Folk-Lore: Printed Extracts no. 2: Suffolk, collected and edited by the Lady Eveline Camilla Gurdon (London, The Folklore Society, 1893; facsimile reprint, Felinfach 1997), p.200. She in turn got it from The East Anglian: or, "Notes and Queries", ed. Samuel Tymms (Lowestoft, 1869-84), vol.3, p.57. If this periodical (which I have not myself seen) is an annual, the date of vol.3 should be 1871, but of course it might be a quarterly or monthly journal. Judging by the style and contents, I would think that Tymms was quoting a 17th century pamphlet, which perhaps some of the Newsletter's readers may be able to identify and locate.

Here is the account:

At St Edmund's Bury, Suffolk, Sept 6, 1660, in the middle of the Broad Street, there were got together an innumerable company of Spiders of a reddish colour, the spectators judged them to have been so many as would have filled a Peck [= a vessel holding two gallons]; these Spiders marched together and in a strange kind of order, from the place where they were first discovered, towards one Mr Duncomb's house, a member of the late Parliament, and since Knighted; and as the people passed the street, or came near the spiders, to look upon so strange a sight, they would shun the people, and kept themselves together in a body till they came to the said Duncomb's house, before whose door there are two great Posts; there they staied, and many of them got under the door into the house, but the greatest part of them, climbing up the posts, spun a very great web presently from the one post to the other, and then wrapt themselves in it in two very great parcels that hung down near to the ground, which the servants of the house at last perceiving, got dry straw and laid it under them, and putting fire to it by a suddain flame consumed the greatest part of them, the number of those that remained were not at all considerable; all the use that the Gentleman made of this strange accident, as far as we can learn, is only this, that he believes they were sent to his house by some Witches.

The reporter's final comment that the only "use" Mr Duncomb made of the event was to suspect witchcraft is probably meant as a criticism; it was normal in those days to see the hand of God (or the Devil) in any astonishing event, interpreting it as a moral warning, a "Judgement", or a "Providential Mercy", so Mr Duncomb's failure to draw any edifying lessons from his spiders may have been slightly shocking.

Be that as it may, we have here spiders as a witch's emissaries besieging, and in some cases entering, the house of an upper-class man, but defeated and destroyed by fire. True, they must have been very small spiders, as an "innumerable company" of them would only fill something about the size of a pail, whereas MRJ's spiders are few, but disgustingly big. But there is enough common ground between the pamphlet's anecdote and MRJ's fiction to suggest that he found inspiration there. It is already accepted that though he set his story in 1690 he was inspired by a famous witch-trial at Bury St Edmunds in the 1660s;[1] here is more evidence pointing to the same place and period.

Note:

[1] "Bury St Edmunds was the site of a number of witch trials in the seventeenth century. There was no trial in 1690 however, and Mother Munning, accused in 1694, was acquitted. Therefore the trials of Amy Duny and Rose Cullender in 1664 were probably the inspiration for MRJ's invention. Though no Sir Matthew Fell was a witness, the judge was Sir Matthew Hale. He admitted the most dubious testimony, as a result of which the two were condemned to be hanged" (Annotations to "The Ash-Tree" in Ghosts & Scholars 11, 1989, p.32; reprinted in M.R. James, A Pleasing Terror: The Complete Supernatural Writings, Ash-Tree Press, 2001, p.40).

The Haunted Baronet is the second of Ash-Tree Press's three-volume series intended to cover the short supernatural fiction of Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu in chronological order; and it is, in many ways, going to be the best of the three, since it includes work from his most productive and atmospheric period.

If you are new to Le Fanu, it may just be worth quoting the views of M.R. James on this genius of the weird, who is generally agreed to have delineated the present form of the genre:

He stands absolutely in the first rank as a writer of ghost stories. That is my deliberate verdict, after reading all the supernatural tales I have been able to get hold of. Nobody sets the scene better than he, nobody touches in the effective detail more deftly.

You should need no further recommendation to buy this book!

It is true that, along with these virtues, Le Fanu had many faults, and they are made cogently clear in Jim Rockhill's excellent introduction, in which he proceeds with the same accurate and realistic assessment he began in the first volume (Schalken the Painter - see my review in G&S Newsletter 3, January 2003). Mr Rockhill continues sifting the many legends and writings about Le Fanu for factual truth, and we are much the better for it. A good example is his pointing out that the label "recluse", attached to Le Fanu's latter years following the death of his wife, while making a good 'story', is simply not true.

The period covered by this book begins with Le Fanu's acquisition of The Dublin University Magazine, to which he was to contribute a steady stream of work. It also saw the production of his greatest novels. Mr Rockhill deals with these briefly but accurately, listing each year's considerable output. Any era in a writer's life that included such original and imaginative novels as Wylder's Hand, Uncle Silas and Checkmate could reasonably be considered his best years. The seven stories here reflect this: the delightful "Borrhomeo the Astrologer" for one; "Squire Toby's Will" for another; and - arguably the most famous ghost story ever written - the grim and relentless "Green Tea" (which Jack Sullivan named "the archetypal ghost story" in his fine study of the English supernatural tale, Elegant Nightmares, 1978).

If you want a good example of Le Fanu's 'scene-setting' and his building up straw-by-straw of the tension that will eventually break the camel's back, just read his description of the Rev. Mr Jennings making his tea, as he wrote - late into the night - on the religious metaphysics of the ancients, innocently unaware of what he was 'brewing up' (if you'll pardon the pun) for himself! In the character of the 'occult specialist' Dr Martin Hesselius (possibly the first occult consultant of fiction), we have the puzzle that, despite Hesselius' own pompous claims to omniscience (and those of his secretary), Le Fanu presents him as an incompetent bungler who wantonly (if carelessly) throws away the life of his client after promising him help at all times. This 'consultant's cock-up' became almost an established pattern with so-called omniscient humanitarians - none more so than Algernon Blackwood's John Silence.

For once, the frequent anthologisations of "Green Tea" are an accurate measure of the quality of the story: it is, indeed, one of the greatest.

But the cream of this volume is the novelette, "The Haunted Baronet". Set in that almost fantasy district of Golden Friars, this tale of a family feud and revenge is a little masterpiece of atmosphere, description and scintillating suspense. Just as it vivified E. Bleiler's famous Dover Books selection of Le Fanu's Best Ghost Stories, so it dominates this present book. It is one of the few supernatural novels that no-one should miss.

The Haunted Baronet is produced to the usual high standards we now take for granted with Ash-Tree, but the colour dust-jacket by Douglas Walters, while striking, is unfortunately not to my taste.

Rating (out of a max.5 stars): ****

A good number of us used to listen eagerly to Sheila Hodgson's plays on BBC Radio 4, originally deriving from M.R. James's "Stories I Have Tried to Write". The later ones had no basis in the Provost's own work, and tended to use less of what we think of as Jamesian techniques in the telling, but they were literate, true to their period, and satisfyingly creepy. Monty James, played by David March and later by Michael Williams, was the ideal storyteller.

With The House at World's End Stephen Sheridan strides out boldly in Sheila Hodgson's footsteps. Rather than have Dr James address the radio audience directly, however, the author introduces him by way of two undergraduates of King's College who are obliged to stay in Cambridge instead of joining their families for Christmas. The Provost invites them to join the little party in his rooms on Christmas Eve, to hear his new ghost story - but when they arrive, they learn that he has instead decided to tell what he claims is a true and terrible story of his own student days.

John Rowe is very happily cast as M.R. James; not as acerbic as David

March, but giving the impression of authority and amiability that comes

across in James's own writings. His is the sort of voice that lends credibility

to the macabre events that young Monty James and his friend Gilbert witnessed

at a remote manor house in Cornwall on a Christmas long ago. He is well

supported by the rest of the cast, particularly David Collings as the enigmatic

physician, and the production team.

The story centres upon an evil and mysterious old book, De Regni Umbrorum

[sic] - otherwise The Kingdom of Shadows - and the search

for forbidden knowledge. Perhaps the theme is more HPL than MRJ, but it

is effectively told, with some nice Jamesian touches. We learn that more

than one person is seeking for the book, and in time we learn the identity

of the second searcher; the revelation is neatly handled and appropriately

chilling. Three people come to a bad end because of the book; two have only

their own callous greed to blame, but the third, like Mr Wraxall, Mr Burton,

and Professor Parkins, is guilty of nothing more than curiosity and being

in the wrong place at the wrong time.

A long time ago Stephen Sheridan wrote a broad Jamesian parody for Radio 4, The Teeth of Abbot Thomas, which gave Alfred Marks the opportunity to overact like mad. It was plain that the author had an affection for the ghost stories of M.R. James, and it is now apparent that he knows his subject well. The House at World's End is a splendid start. I trust that the BBC will give us more pleasant terrors from Stephen Sheridan - and perhaps some dramatisations of MRJ's own stories. How about "The Ash-Tree" or "The Tractate Middoth" for a start? Think about it, Mr Sheridan, please.

Rating: ***½

go to Newsletter Issue 1

go to Newsletter Issue 2

go to Newsletter Issue 3

go to Newsletter Issue 4

back to Jamesian News Page

back to Ghosts & Scholars Home Page