Go

to the Archive index

Go

to the Archive index

The year was 1953. I had been motoring around for some two years on a bicycle fitted with a Mini-Motor (see Buzzing, Feb 2005), and was beginning to toy with the idea of upgrading to a true motor cycle when I was quite unexpectedly offered a Brockhouse Corgi. This was a small, folding motor cycle which had evolved from a military version intended to move troops rapidly after parachute drops and known as the Welbike. The machine had its origins in World War II at a secret SOE establishment called the Frythe, a country house near the village of Welwyn in Hertfordshire. Requisitioned in 1939, the establishment was responsible for many unconventional warlike devices. Reflecting their place of origin, the names of some of these carried the prefix Wel, such as the Welrod, a .22 silenced pistol, the Welwand, an assassination pistol intended to be concealed up the sleeve and the Welgun, a 9mm submachine gun. Thus the Welbike got its name.

The frame and engine layout of the Corgi and Welbike were similar, but the Corgi had been made less skeletal and basic in appearance by changing the shape of the petrol tank and situating it in the more conventional motor cycle position between the handlebars and the saddle. Both vehicles had small wheels and could be made very compact by telescoping the saddle post down into a tube and folding the handlebars back and flat over the petrol tank. Both were powered by a 98cc two-stroke engine and had only one gear. I believe that the Mkl Corgi had to be started by pushing, but the one I was offered was a Mk2 with kick-start and two clutches. A standard, handlebar-operated clutch connected the engine to the rear drive and a dog-clutch, operated by folding down the right-hand footrest, made the final connection to the rear wheel. This arrangement enabled you to kick-start and run the engine with the vehicle stationary. Once the engine was running, you moved off by pushing the footrest flat between operating and releasing the handlebar clutch.

The owner of the aforesaid Corgi lived next door to a friend of mine, which is how I came to hear about it. The machine was about three years old and he wanted £25 for it, so I set out with £23 cash stuffed into one pocket, and £2 in another, in case required. The seller turned out to be a smooth-talking old gentleman who, on my arrival, immediately launched into a lengthy monologue extolling the delights of the machine, how he used it daily to travel all over the city, it had never let him down, he was reluctant to let it go, and so on. "'What's it like on the hills?" I interrupted, bearing in mind that it had only one gear and no pedals. He was unequivocal. He used it daily, he said, to travel to and from the local main line railway station which indeed lay at the bottom of a hill. When it came to the possibility of a trial run, he found plenty of reasons, mostly legal, why I couldn't take it on the road but, eventually we wheeled it round the corner to a (flat) car park where I was permitted to make one or two circuits. The engine started easily enough and apparently ran satisfactorily and, being a sucker for the curious and bizarre, I liked this unusual machine and offered him £23 which he accepted without hesitation. In 1953, the age of instant everything had not yet dawned, so it was a week before insurance and transfer of ownership were complete but, eventually the day came and I collected the machine. It may be of no significance, but the gentleman who sold me the machine was apparently not at home when I called and I was shown through the house to a yard at the back, by an elderly woman who handed me some relevant documents and indicated the bike and a gate in the garden wall, leading to an alley beyond. Our city at the time - Exeter, is quite hilly and I hadn't gone very far when I found the bike labouring to get up quite modest inclines. Anything a bit steep and the engine gave up altogether. In fact, I had to push the machine up the last leg of the journey as we lived up a steep hill. By the time I arrived home I was, to paraphrase James Bond, shaken but not too deterred as the machine did go and there couldn't be too much wrong with it.

However, like Rick and the waters of Casablanca, I had been misinformed and, puzzled as to why it did not live up to the sales talk, I wasted a couple of weeks endlessly cleaning the spark plug, the contact breaker points, the carburettor, and tinkering about generally in the vain hope that I must have overlooked something. Then a knowledgeable friend turned up and took a critical look. "The exhaust is choked," he said bluntly, "it's probably been like that for ages." The Corgi exhaust system consisted of two short pipes, leading to and from the silencer which was simply a cylindrical steel tube, with alloy end caps, situated under the saddle and through which the exhaust gas passed on its way to the atmosphere. Inside I found a plate dividing the tube in two and drilled with holes, most of which, sure enough, were choked up with carbon. I started to clear them out but decided I would prefer a snappy exhaust note, so I removed the plate altogether.

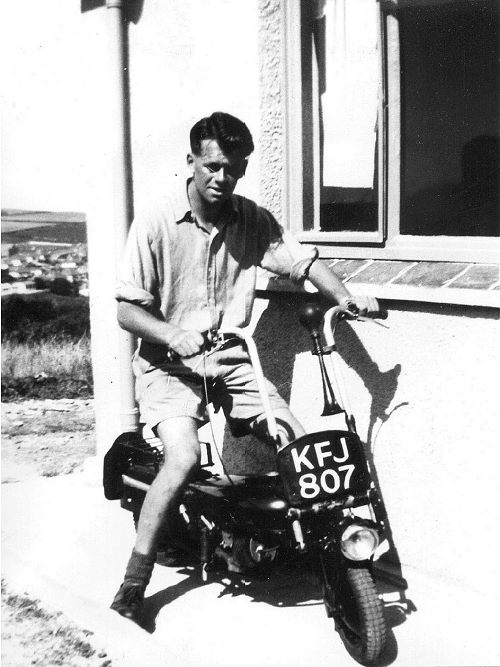

Reflecting the age of shortages and economy in which it appeared, immediately after the Second World War, the Corgi was basic. There was no electric horn, there was no speedometer and I don't remember a battery. I think the head and tail lights were powered directly from lighting coils in the flywheel magneto as the brightness varied with engine speed. There was no spring suspension on either wheel and, of course, there was only one gear. There was no provision for security but, in those days, if you left a vehicle unattended, there was every chance that it would still be there when you returned. For all that, I found the Corgi a very comfortable and easy machine to ride. With its small 12½ inch wheels, most of it was close to the ground, so it had a low centre of gravity that made it manoeuvrable and easy to balance, particularly at low speed in the city traffic. Despite the small wheels, the tyres were relatively wide and, if not inflated too hard, readily absorbed minor undulations in the road surface. I much preferred the freedom of personal travel to public transport and was prepared to drive anywhere. The photograph was taken in North Cornwall, about 100 miles from home. Being small, the Corgi was no trouble to park. You could go into a shop and leave it on the pavement outside without causing an obstruction. As for tinkering with the engine or maintenance, it was a dream. You could, and I did, bring it indoors and lift it on to the kitchen table.

If I ever thought that a lack of pedals and only one gear would be an embarrassment in a standing start on a hill, I found that, in practice, this was not the case. The designer must have had this in mind and compromised with a gear low enough to cope with most hills, while being able to maintain an acceptable speed on the flat or downhill. Ironically, the one steep hill that might have defeated the Corgi was where we lived, but I never found this out as it was a cul-de-sac at the top end and I never had to climb it from a standing start.

Being three years old, some parts were worn and, sooner or later, gave trouble. I had to re-line the brakes, the HT cable was intermittent and a tyre split and had to be replaced. Fortunately, there was a motor dealer in the town who carried a good range of Corgi spares. More irritating was the engine's habit of stopping after being driven hard in hilly districts - that is, when it got hot. I quickly discovered that, under such conditions, a whisker of carbon frequently formed across the spark gap. So, I always carried a plug spanner, although careful driving generally prevented such an occurrence. The Corgi, which lasted me for about eighteen months, was soon forgotten when I graduated to a full-size motor cycle, starting with an ex-WD Royal Enfield of 350cc capacity. Some 20 years later, I came across the mouldering remains of a Corgi in a motor scrapyard and never gave it a second glance, but recently I saw a Welbike in a military museum and memories were re-awakened. If I had to make a final comment on my Corgi days, it would have to be: "I wish I still had it."

First published, October 2005