DEFENCE OF THE PORT OF WORKINGTON:

The 406th Coast-Battery of the 561st Coast Regiment, Royal Artillery

Workington Battery Contents

Following the evacuation from Dunkirk in May 1940, it soon became evident that Hitler intended to invade Britain. With this in mind, plans were drawn up to surround our islands with a ring of coastal defence artillery, designed to cover every probable landing-place. A hoard of guns - of various calibres - from scrapped WWI battleships had been squirreled away in the Royal Navy stores and this supply was now drawn upon to furnish the 'Emergency Coast Batteries', of which Workington and Whitehaven were good examples.

Following the evacuation from Dunkirk in May 1940, it soon became evident that Hitler intended to invade Britain. With this in mind, plans were drawn up to surround our islands with a ring of coastal defence artillery, designed to cover every probable landing-place. A hoard of guns - of various calibres - from scrapped WWI battleships had been squirreled away in the Royal Navy stores and this supply was now drawn upon to furnish the 'Emergency Coast Batteries', of which Workington and Whitehaven were good examples.

Workington dock was considered a vital artery to Cumberland and the north for the import and export of material essential to the war effort. (As examples, on Good Friday 1944, a cargo of gliders was brought into Workington dock by boat, later to be sent down country by road haulage. General Montgomery's motor car and equipment was also brought into the country via Workington.) It was classed as a 'Minor Port', as was Whitehaven. Maryport was classed as a 'Beach-Battery'.

Enemy attacks by fleet action on the West Cumberland coastline were considered unlikely. It was thought that the greatest threat would be an audacious invasion attempt with violent assaults on coastal defences by the use of gas, dive-bombers and machine-gunnery. Enemy troops would use light craft and parachute landings in an attempt to secure a beach-head. Port and harbour installations were considered to be under threat from close-range warship gunfire and blockships. Enemy submarines were thought to be a likely form of attack.

Construction of a group of eight batteries - including Workington - was started on the 21st July 1940. Workington battery was in the third of seven phases of construction of the one hundred and fifty-three emergency coast batteries built around Britain. The plans were to have three four-inch guns at Workington, but the third gun was never used there and was emplaced at Maryport, five miles up the coast, at the site of the Victorian gun-battery on Sea Brows. Although the guns were plentiful, an initial supply - on average - of fifty rounds of ammunition was all that was allocated to each battery. The Workington guns were known as the 406th Coast-Battery and were manned by the 561st Coast Regiment, Royal Artillery. Operational instructions (No:1) were drawn up for the 23rd Coast Artillery Group on 10th December 1940, which included plans to liaise with local infantry units - 'A' Company of the 9th Border Regiment - and the RAF at Silloth. Assistance from the Infantry and the RAF would only be used to help defend the coast if the general war situation allowed it.

The battery construction project was undertaken by a group consisting of a gun-mounting party, experts from the Coastal Artillery school, Royal Navy sailors and gunners who would man the guns once in position. Contract labour was used to build the battery, led by the Royal Engineers Services. Construction of the gun-houses and searchlight emplacements was made using copious supplies of quick-setting concrete.

The Workington battery fell under the command of the 23rd Coast Artillery Group who were responsible for defending the Cumberland coastline (Whitehaven, Workington and Maryport), and a Royal Naval Examination Service was provided at Workington and Whitehaven. Although Workington, Whitehaven and Maryport were grouped as the 561st Coast-Regiment (as is clear from War Diary entries and the original Battery Instructions), the anomaly of which number the regiment was remains; the 'Tatie-Pot Supper' menu and contemporary newspaper report clearly shows Lieutenant R. Lawson (Dick Lawson) as toasting the 562nd Coast-Regiment, R.A. The change in Coast-Regiment numbering is thought either to have occurred with Royal Artillery Coast-Regiment reorganisation later during the war (Operation Neap-Tide, when many of the regular gunners were deployed elsewhere as the threat of invasion was then considered unlikely), or when the entire R.A 'regulars' were replaced in January 1944.

Enter the Home-Guard

It was decided by the War Office to enrol members of the Home-Guard - preferably former Artillerymen - into some of the Royal Artillery coastal batteries. In December 1941 a recruiting advertisement was published in the local press, resulting in the formation of a small Home-Guard unit attached to the RA in January 1942. Response to the advertisement was largely taken up by members of the Special Constabulary, who were - up to now - unable to participate in Home-Guard activities.

This was serious stuff.... Naval guns were somewhat different to the Smith-guns, Northover Projectors and pickaxe-handles which had previously been the stable armoury of the Home-Guard! The coastal volunteers quickly took it upon themselves to learn the intricacy required to operate these monsters, which had been taken from a WWI battleship and could fire Armour-Piercing or high-explosive rounds as required. The men learned well, too - initially under Captain Hughson, R.A., and then-on following a training programme drawn up by Lieutenant Cane, R.A. and Sergeants Jimmy Vallance and Johnny Mowatt. Training was of such a high calibre that before long the Home-Guard gunners found themselves entitled to wear the RA red and blue flash and the white lanyard. Before actually getting their hands on the guns however, the Home-Guard had witnessed a 'bring-to' incident, where the regulars had fired at a vessel failing to respond to a signal.

Weaponry and Layout

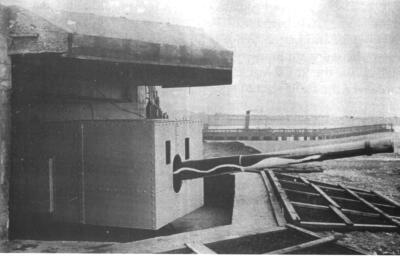

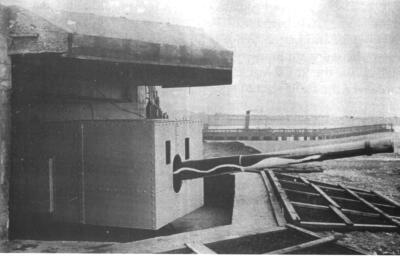

Along with the actual weaponry - Two hand-triggered four-inch BL (Breech-Loading) Mk. VII guns of 1912 and 1914 vintage - battery operations (HG and 'Regulars') consisted of searchlight operation, engine-room maintenance and battery-observation post duties. Anti-aircraft protection was also offered for the coast battery and was catered for by electrically operated rocket-projectors ('ZAA'-Batteries). A 75mm field-gun of French origin was on hand as an auxiliary weapon, upon which all the Home-Guard Gunners were trained. It was designed to be used to defend the battery from landward attack, was entirely portable with a 360 degree arc and a range of 3,000 - 5,000 yards and could also be used to have a crack against enemy vessels if the four-inch main guns were put out of action.

The role of the battery was prioritised as follows:

- Anti-shipping.

- Support of the Royal Naval Examination Service.

- Defence of the beach and shoreline.

- Landward defences.

None of the above roles were to be adopted if the possibility existed of adopting a role of greater priority.

A graphical illustration of the layout of the battery and a RAF aerial photograph taken on 19th May 1948 show where everything was. Further details of the battery layout were derived from another aerial photograph taken on 16th January 1946.

The four-inch guns were in two casements 30 yards apart. Each consisted of a gun-floor, a magazine containing an abundance of Armour-Piercing shells plus cartridges and H.E. shells, a war (or 'watch')-shelter and an access corridor from the entrance at the rear of the casement to the gun-floor, between the magazine and the shelter. Fifteen rounds of High-Explosive shell per gun along with associated tubes and cartridges were to be kept on the gun-floor. Fuse-caps with safety-pins removed were to be kept nearby, all for instant use.  The guns stood where the small car-park and one of the wind-turbines now stand atop the slag-bank on Northside shore. No:1 gun was nearest the dock; No:2 the northernmost one. They had a horizontal arc of 80 degrees and a range of between 2,000 and 10,000 yards. Normally 6,000 yards was considered to be the limit of effective range. Firing further than this distance was at the discretion of the Battery Commander, and was only to be used at enemy vessels committing hostile acts against the shore, or against British or Allied shipping.

The guns stood where the small car-park and one of the wind-turbines now stand atop the slag-bank on Northside shore. No:1 gun was nearest the dock; No:2 the northernmost one. They had a horizontal arc of 80 degrees and a range of between 2,000 and 10,000 yards. Normally 6,000 yards was considered to be the limit of effective range. Firing further than this distance was at the discretion of the Battery Commander, and was only to be used at enemy vessels committing hostile acts against the shore, or against British or Allied shipping.

The Regular Army (Royal Artillery) battery personnel were divided into three watches of eight hours each, while the Home-Guardsmen on night-duties paraded at 19:25 and were dismissed at 06:00. Each watch contained sufficient officers and men to command and staff the battery, and to fire both guns at the maximum rate of fire for two minutes. The Duty Watch were to be at readiness, fully equipped, and within ten seconds of their respective posts. If visibility by day exceeded 8,000 yards, the state of readiness was reduced to one minute. During day-watch, no member of the watch was to lie down or sleep. On night-watch, provided the searchlights were not in use or that the states of 'ARRAS' and 'NEWTON' (below) were not in force, sleep was permitted in the watch-shelters with the exception of the Officer of the Watch and those who were on 'look-out' duties. All equipment was prepared for action twice daily: At first light and before dusk. Alarm gongs at the war and reserve shelters, the searchlights, and the engine room could be sounded from generators at the BOP.

The battery would act accordingly on receipt of code-words attached to certain messages:

- ALTMARK: No action necessary

- ARRAS: All troops to be in barracks by 22:00hrs. State of readiness of the Duty and Reserve watches to be ten seconds and two minutes respectively, under all conditions. By night, a full state of readiness will be resumed with the whole Duty Watch awake.

- NEWTON: As 'ARRAS', but Reserve Watch to take the post for ammunition supply. The remainder of the battery personnel to defend the inner perimeter. By night, a full state of readiness will be resumed with the whole Duty Watch awake.

- OLIVER: As 'NEWTON'.

- NARVIC: Revert to normal state.

A second watch stood by as reserve, within two minutes of their respective posts. When visibility by day exceeded 8,000 yards, this state of readiness was reduced to five minutes. This reserve watch was allowed to sleep in the reserve watch-shelter, but were to remain fully-clothed with steel helmets and anti-gas equipment at the ready. Observation and sentry-duties were undertaken as shown below:

BY DAY

- 1 Gun look-out

- 1 BOP look-out

- 1 Telephonist

- 1 Air sentry

- 1 Sentry on perimeter guard

|

BY NIGHT

- 2 Gun look-outs

- 1 BOP look-out

- 1 Telephonist

- 1 Searchlight sentry

- 1 Sentry on perimeter guard

|

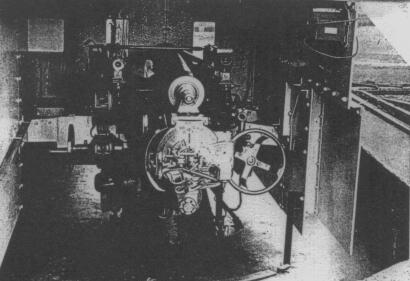

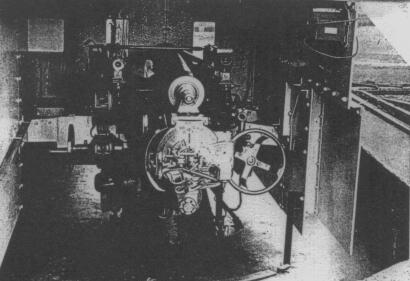

Gun-aiming instructions derived from the two ranging instruments ('Barr and Stroud' and 'Dumaresq') on the Battery Observation Post (BOP) were relayed to the gunners by telephone and a via a large loudspeaker located in the corridor between the gun-floor and the war-shelter. The initial instruction from the BOP would be: 'Ranging Salvos'. Both guns then fired simultaneously at the settings taken from the ranging instruments. Further observations of the target from the BOP would be relayed to instruct the gunners to add (or subtract) numbers from their handwheel settings. This would be done incrementally and bracketed so that the guns homed in on the target. The responsibility for opening or withholding fire lay with the Battery Commander.

Once the guns were aligned, the next instruction from the BOP would be: 'Gun-Fire'. This meant the guns firing independently, each gun being 'fine-tuned' individually by the Ranger (No:3 below). When vessels were determined to be hostile - or potentially hostile - or had committed a hostile act, engagement took place. Shooting could also be summoned by the Royal Navy Examination party signalling to the Battery Commander by the signal-hoist, a green Verey-light, or by the Morse signal '8' (dah-dah-dah-di-dit) on an Aldis-Lamp.

If any vessel - not definitely recognised as friendly - had proceeded towards the coast after failing to obey a 'stand-still' signal from the battery, it, too was considered fair game for the gunners. 'Common-Point' shells were to be used against warships and submarines, H.E (High Explosive) shells against 'E'-Boats, merchant vessels, aircraft on land or sea, and personnel.

There was a crew of eight on each gun. For shooting both guns at the maximum rate of fire for two minutes, a crew of nine-per-gun was desirable, with a crew of seven-per-gun being the bare minimum.

- No:1 - Gun Commander

- No:2 - Line-Layer (Positioned RHS of the gun and controlled the azimuth alignment)

- No:3 - Ranger / Firer (Positioned LHS of the gun and controlled the elevation)

- No:4 - Breech and detonator-cap

- No:5 - Shell loader

- No:6 - Ram-rod

- No:7 - Ram-rod

- No:8 - Cartridge

The whole affair was choreographed so that nobody obstructed anyone else. Upon loading the cartridge with his right hand, No:8 would withdraw his hand and slap his own backside, at the same time shouting: 'Out'! - enabling No:4 to close the breech and fit the cap without removing No:8's arm at the elbow. No:8 then shouted: 'Fire"! and No: 3 fired the gun. All eight positions were interchangeable, with each man learning how to undertake all tasks required so that - if necessary - they could step in for one another. No:8 would take the position of No:1, No:2 of No: 3 etc... In an emergency, the guns could be operated by lanyard and - once a battery Home-Guardsman was suitably qualified as a gunner - a white lanyard was worn as part of the uniform.

Shooting ceased when the target had been destroyed or disabled; when a more tactically-important target presented itself, or if the vessel had been deemed 'not hostile'. The latter decision may have been made if suitable intelligence had been passed on to the Battery Commander. The 'cease-fire' signal from the Royal Naval Examination Vessel consisted of a white Verey-light or a Morse signal '4' (dit-dit-dit-dit-dah).

BOP, Bring-To, Rockets, Batteries, and Searchlights

In an elevated position twenty yards to the east and slightly behind the gun-houses was the Battery Observation Post (BOP). From here, liaison by telephone with a Marine detachment took place, whose job it was to signal to all vessels steaming northwards to halt, using either Aldis-Lamp or international code-signals. The Marines - who were based in the 'XDO' post near the dock - would then send a Royal Navy Examination party out to the vessel in a pilot-boat (Examination Vessel) to investigate. The 'bring-to' area which the guns covered was marked out by two buoys about two miles apart, delineating a sea area known as the 'Workington Roads'. The southernmost buoy was approximately in line with the south pier. Any vessel steaming up the Solway Firth had to halt within this area, and failure to do so would result in a 'bring-to' round being fired! A request to 'bring-to' a vessel could be made by the Royal Naval Examination party, who would summon the request by the signal-hoist, a blue Verey-light or by the Morse signal '2' (dit-dit-dah-dah-dah) on an Aldis-Lamp. Failure to 'bring-to' after one or more rounds would result in high-explosive or Common-Point rounds being used to deadly effect.

Any situation which would have put the battery at risk and unable to fulfil its role was justification to fire a 'bring-to' round of sand-filled shells, of the type used for practice shoots.

A Dutch ship fell foul of the regulations one time and didn't stop as required. The Marines signalled to it to no avail and it continued to steam northwards. A 'Bring-To' sand-filled round was fired, after which the intentions of the battery were quickly and unequivocally understood and the ship  ground to a rapid halt!

ground to a rapid halt!

The two searchlights, or D.E.Ls (Defence Electric Lights) stood nearby, 323 yards between them. One stood 180 yards to the north-east of No:2 gun and one 136 yards to the south-south west of No:1 gun, behind sections of sea-defences which have now been 'landscaped'. The north searchlight may have been automatically steered (using a 'SELSYN' or 'MAGSLIP' arrangement - or similar) and controlled from the BOP. The searchlights were operated in such a way that one of them could be manned and brought into action from the BOP within ten seconds, with the second searchlight brought up to readiness within one minute. The auxiliary engine was attended to at night by the engine-house assistant, in case there was a failure of the main engines and generators.

Apart from the heavy concrete and steel block-houses, the battery consisted of a camp which lay behind the slag-bank, between the gun-houses and the dock and surrounded by an embankment to form - roughly - a horse-shoe shape. The 'ZAA'- Battery rocket projectors were sited on this embankment. These multiple-launch anti-aircraft devices were merely large frames holding sixteen electrically-triggered rockets (eight on each side, also known as 'UP's - or 'Unrotated Projectiles'), which had been developed for use against aircraft - the Dive-Bomber fuzed at 3,500ft and high-level bombers, fuzed at 20,000ft - and trialled at the Aberporth Rocket Testing Range in South Wales. They were aimed and detonated by a soldier or Home-Guardsman sitting within, who operated the whole thing by means of two foot-pedals whilst looking skywards through a 'spider's web' sight.

'Z'-Battery rockets (UP's) were really akin to large, deadly fireworks. The 'Regulars' were testing the rockets one afternoon and a projectile was observed to fail mid-flight and splutter earthwards, landing on the cliff-edge with the nose pointing inland. It re-ignited, whizzed off skywards again in the wrong direction and shot through a council-house roof on Derwent Avenue, Seaton! It is not recorded whether any injuries occurred as a result of this unfortunate incident.

The Battery Headquarters were part of the camp (the first recruits, however, enrolled at Workington Police Station), as was a NAAFI, a barracks for the R. A. Gunners, an Officer's mess, a barracks for the Marines, a cook-house, medical quarters and latrines. These buildings were temporary structures of the 'Nissen-Hut' variety. A more substantial rectangular squat building and a brick-lined air-raid trench alongside it stood immediately behind the steep inland fall of the slag-bank, adjacent to the generator-house.

The battery was able to communicate with the world beyond the perimeter fence, as there was a private direct-line telephone link to Group HQ. A GPO civilian exchange connection was also established, and designated 'Workington 542'. Internal battery communications were arranged whereby the Battery Commander was linked by telephone from the BOP to the searchlights, the engine-house, and the Battery Office.

The entire battery encampment was self-contained and surrounded by two barbed wire fences (inner and outer), separated from each other by a mined area several yards wide. This secure inner encampment was provided with three days' reserve rations and a full water tank. There was one way only onto the battery - along the Oldside road - which was guarded by armed sentries. In amongst the huts and barracks was an assault-course, where infantry training - using flash-bombs and live ammunition at times and watched over with delight by Major Copley - took place. There was a 200-Yard rifle-range outside and a miniature gunnery range in a lecture room, where the Home-Guard Gunners assembled daily before being allocated their duties. The miniature range was a tiny replica of the real thing which stood on a table about chest-height, with protruding targets operated by someone underneath the table. All trajectories and other gunnery measurements could then be worked out and scaled up proportionally when the real guns were used.

Unlike Whitehaven battery, there were no Lewis-Gun emplacements at the Workington battery (though a Lewis gun is mentioned in a War Diary incident), but there were Bren and Sten guns issued and kept in the battery armoury. Training on these robust instruments of mayhem was provided in the old quarry at Embleton, with lorry-loads of Home-Guard Gunners being taken the twelve miles for machine-gun practice, or extra fuel coupons issued to allow transport there by car or motor-cycle. Personal .303 bolt-action rifles were issued to the Home-Guard. There were Anti-Aircraft Lewis-guns dotted around the Workington Iron and Steel Works, manned by the Home-Guard and the Cheshire Regiment at Salterbeck, a mile or so south-west of the battery.

This training was to enable the Home-Guard gunners to fight alongside the 'Regulars' in a rearguard attack if invaded from the landward side of the battery (a precaution exacerbated by events instrumental to the fall of Singapore). To this end, there were two crescent-shaped 'dug-outs' sited behind the north searchlight position and behind the 'ZAA' rockets nearest the BOP. They were in a commanding position on the top of the landward-side of the slag-bank, in a position to be manned quickly, without confusion, and with maximum fire-power. Approximately one-third of the battery personnel were available for landward defence, having regard to the priority of the four-inch naval guns. The battery personnel were responsible for defending the battery to the inner fence. Further infantry training for the Home-Guard contingent was undertaken on land adjacent to Hunday Farm, to the east of the town. On occasions such as this, the Home-Guard Gunners put in a rare appearance outside of the battery perimeter fence!

Vessel Docking Rules

Following Churchill's instruction to arm merchant vessels, any boat which found itself docking at Workington had to berth either side of the dock gates, with stern (gun-end) pointing out to sea. The vessels then fell under the jurisdiction of the Battery Observation Post and meant that the Workington coast-battery 'fire-power' was augmented for the duration of their stay in port.

The gunners practiced at the RA Coastal Artillery school in Llandudno and also visited the

coast batteries at Barrow to participate in exercises, consisting of firing at 'Hong-Kong' targets at sea. A 'Hong-Kong' or 'toy-boat' target consisted of a mile or so of cable hauled by a tug, at the other end of which were two buoys separated by a rope the length of a ship. This was then shot at - occasionally breaking the rope itself! The tug hauled the target north up the Solway Firth when practicing at Workington.

'Tank-busting' exercises took place on Workington shore, against sea targets with the 75mm field-gun. Competitions were held from time-to-time with the Home-Guard versus the RA, good results being obtained always by the Home-Guard. 75mm field-gun practice against moving targets also took place at Walney Island.

The End In Sight

Came the end, and on the 9th November 1944 the Home-Guard Gunners were invited to a 'do' in the Regular Sergeants' mess. When the Workington Home-Guard stood down on that wet, dull day which was the 3rd December 1944, the platoon attached to the coast battery did not take part in the Oxford Street parade, but fired an eight-salvo salute as the other battalions

marched through the town and took the salute.

On the 14th December, a farewell 'tatie-pot' supper - organised by Sergeant Major Goss - was held in the Sergeants' mess, at which were present Major Winter, O.C. 562nd Coast-Regiment, along with Officers, Warrant-Officers and Sergeants of the 406th Coast-Battery.

It has been given to me, as Regimental Commander in Coast Artillery for more than four years, to be in at the birth of several fine bodies of Home Guard Coast Artillery Personnel, and to watch them and try to help in their steady advancement towards becoming Gunners of high proficiency and outstanding zeal. Of these colleagues of mine, men whom it has been a delight and honour for me to number as operational members of my Regiment, there is no section, sub-unit or battery which stands out more prominently as an example of the qualities and attainments required for this great service, than the Workington Coastal Artillery Home-Guard.

For Keenness, enthusiasm, accomplishment, comradeship - yes, for all the most desirable attributes needed to reach the common end, they have no peers.

I was an honoured guest at their farewell function at the Battery; it was my joy then to give expression, as best I could, to a few of the thoughts that had come to my mind. I now take this opportunity of asking them 'Hard Livers', 'Hard Workers', and 'Hard Fighters', to accept from me, and in the name of the whole formation comprising the 562nd Coast Regiment R.A a simple, big 'Thank-You' for what they did, all that they would have done had the need arisen and, above all, for their presence within our midst. God bless them.'

|

Stories were exchanged, jokes were told, drink was drunk and Major Winter's thoughts were composed - later to be reflected in a congratulatory message (left) expressing sincere gratitude and thanks for all which was done and would have been done, should the need have arisen. Details of this feast were published in articles in the 'West Cumberland Times' and the 'West Cumberland News' on Saturday 23rd December, 1944. - Probably the only publicity the battery had since the discreet advertisement for Home-Guard recruits appeared in December 1941.

The coast-battery camp was dismantled in 1946/7, but the gun-houses, searchlight emplacements and XDO post were left to decay naturally until the 1970's, when a general 'clean-up' of the shoreline removed all traces of these defence works. There are some photographs which show the battery site as it is today, and this photograph - taken by chance from the other side of the harbour - shows the battery as it was in 1958. Coastal guns defended our shores elsewhere however and continued to do so until 17th February 1956, when a decision was made by the Army Council to dismantle the coastal artillery. Warfare had moved irrevocably into the nuclear age, ending a method of defence of our islands going back to 1540, when Henry VIII ruled over us.

A Minewatchers' Post stood just to the north of the dock at shore-level. Located just above the north pier, it was a small concrete block-house with a smaller square concrete loop-holed turret on the roof. Access to the turret was from inside the block-house up a short steel ladder which was fastened to the floor. It has been compared by Philip Carlisle of English Heritage to a similar structure at Kingswear Castle, Devon, which was a mine-watcher's building, or 'XDO' (Extended Defence Officers') Post.

I remember it to be the nearly the last part of the defence of Workington Dock to be demolished - sometime in the late 1970's or early 1980's. As I don't have a photograph of the 'XDO' Post, I have drawn a sketch - from memory - of how I remember it. There are further details on the same page.

The sea area and coastline right up to Silloth was mined to protect shipping lanes into and out of the port and for anti-invasion measures. My Father - in his days as a loco-fireman during WWII - remembers passing over the line between Workington and Flimby many times and of witnessing skull-and-crossbones signs amongst reels of barbed wire, extending from Siddick to Flimby and beyond along the shoreline - a far cry from the days of the fledgling LDV, when two men armed with one stick between them patrolled the shore between Siddick and Flimby, looking for potential invaders.

When the threat of invasion was imminent, the harbour 'gut' was planted with a demolition charge at a point beyond the old pier (The concrete-cube constructed pier, which - at the time - extended to a point where the new pier now stands). The explosives, which were on the southern side of the harbour channel, were either controlled from the old Rocket Brigade station a few hundred yards east, or from this mine-watcher's post. They were partly detonated in 1941/1942 as the threat of invasion lifted. In the late 1970's, however, a routine dredging operation fished up some unexploded ordnance which had not 'gone off' with the other stuff nearly 40 years previously and so was taken out to sea by the Bomb Disposal squad and detonated.

As well as our own mines being sown, enemy mines were dropped into the sea during air-raids , to thwart the passage of shipping.

Sheila Cartwright very kindly provided this picture of mines being cleared at Moss Bay either during or just after WWII, slag-banks in the distance. Tragically, a young Lieutenant involved in mine-clearing was killed at the cessation of hostilities. The mines were set - amongst other methods - with trip-wire attached to protruding pieces of railway-line, which were submerged at high tide. This young officer - who had just got engaged to a Flimby girl - was in the process of removing mines from the West Cumberland shore when it is believed he stepped backwards, detonating an un-cleared device.

Home | Contents |

Workington | Links |

E-Mail | Home-Guard I | Home-Guard II

XDO / Marines Signals Post | Graphic | Coast-Battery Today | 1948 Aerial Photo

Following the evacuation from Dunkirk in May 1940, it soon became evident that Hitler intended to invade Britain. With this in mind, plans were drawn up to surround our islands with a ring of coastal defence artillery, designed to cover every probable landing-place. A hoard of guns - of various calibres - from scrapped WWI battleships had been squirreled away in the Royal Navy stores and this supply was now drawn upon to furnish the 'Emergency Coast Batteries', of which Workington and Whitehaven were good examples.

Following the evacuation from Dunkirk in May 1940, it soon became evident that Hitler intended to invade Britain. With this in mind, plans were drawn up to surround our islands with a ring of coastal defence artillery, designed to cover every probable landing-place. A hoard of guns - of various calibres - from scrapped WWI battleships had been squirreled away in the Royal Navy stores and this supply was now drawn upon to furnish the 'Emergency Coast Batteries', of which Workington and Whitehaven were good examples.

The guns stood where the

The guns stood where the