Greece 1971

Bedford to Salzburg

The photos - mostly taken by Patrick (I didn't believe in photography in those days) started off as slides. They have obviously deteriorated badly - and some are quite useless even with extensive recourse to Photoshop.

You never forget the first time... Actually my first time should have been in 1958 - when Roger Coghill and I confidently set off to hitchhike to Greece. This was in fact Plan B - Plan A was to drive in our jointly-owned 1933 Austin 7 (bought for £25.00 - we wuz robbed). A plan mercifully scotched by my failure to pass the driving test (in fact I didn't even get as far as taking the test - my over-sensitive driving instructor having refused to set foot in our cherished vehicle. And it was indeed cherished. We'd cleaned it and polished it, and even bought it new brakes - they worked like bicycle brakes I remember. And Roger's girlfriend Valerie had even mad some dinky curtains for the back windows. In turned out, eventually, that our ex-friend who sold it to us had done unspeakable things to the engine to prolong its life by a few months.) Plan B only took us as far as Zagreb in Yugoslavia, beyond which there were no vehicles to hitch with - only horses and carts and lorries which either didn't stop, or demanded money - something that would seem to vitiate the entire point of hitching - especially with our very limited funds. I had £25 and Roger a fiver - most of which he spent on sending postcards to Valerie. I said nothing, but it still rankles.

So I kept my virginity for another 13 years, until the summer of 1971, when I was a teacher at Bedford Modern School. This is (maybe) the report I should have written for the Eagle 40 years ago, in 1971. There were eight of us, three staff - myself, Philip Grattidge the Head of Classics (who died in 2003) and Patrick Molony, a very new teacher of Geography and Economics (who later moved to Harrow, and who sadly died in 2009 in his palace in Montenegro. His journey there must have been fascinating, but I was about contact him when I heard the news of his death). The five boys were Richard Janko (now Professor of Classics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), Chris Smale (Head of English at Birkenhead School), Pete Sheppard (last heard of in 2004 as an olive farmer in Crete), Braidwood (known as Buzz because of his haircut - embarrassingly I can't remember his first name), and Michael (even more embarrassingly, I can't remember his surname). The most important member, though, was a white minibus, name (and make) unknown - possibly a Ford? It belonged to another member of staff at BMS - Andrew "The Incredible" Cairncross - who generously lent it to us after Patrick's Landrover suffered a last minute breakdown.

So I kept my virginity for another 13 years, until the summer of 1971, when I was a teacher at Bedford Modern School. This is (maybe) the report I should have written for the Eagle 40 years ago, in 1971. There were eight of us, three staff - myself, Philip Grattidge the Head of Classics (who died in 2003) and Patrick Molony, a very new teacher of Geography and Economics (who later moved to Harrow, and who sadly died in 2009 in his palace in Montenegro. His journey there must have been fascinating, but I was about contact him when I heard the news of his death). The five boys were Richard Janko (now Professor of Classics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), Chris Smale (Head of English at Birkenhead School), Pete Sheppard (last heard of in 2004 as an olive farmer in Crete), Braidwood (known as Buzz because of his haircut - embarrassingly I can't remember his first name), and Michael (even more embarrassingly, I can't remember his surname). The most important member, though, was a white minibus, name (and make) unknown - possibly a Ford? It belonged to another member of staff at BMS - Andrew "The Incredible" Cairncross - who generously lent it to us after Patrick's Landrover suffered a last minute breakdown.

The boys had just got their A Level results. Three had taken Greek, and one was disappointed - a glitch in his otherwise unblemished academic career! (For which I still blame myself - a young teacher too easily distracted from the syllabus.)

The boys had just got their A Level results. Three had taken Greek, and one was disappointed - a glitch in his otherwise unblemished academic career! (For which I still blame myself - a young teacher too easily distracted from the syllabus.)

We met in the garden of School House (PJG was the housemaster) on the afternoon before departure to make sure we all knew what was happening, and to load the tiny tents (army issue - thanks to Dan Dickey and the CCF)

Next morning I drove us confidently through central London (no M25 then), destination - not Dover - but Ramsgate. There we boarded the latest in cross channel transport - the Hovercraft. It took about half an hour to reach Calais - and was capable of speeds of around 150 kph, carrying 250 passengers and 30 vehicles. This was true progress - I'd always dreaded the ferries, having passed several crossings in vomit-soaked cubicles below decks, praying like Odysseus for an early death.

Once across, we drove via Ostend, and spent the night somewhere between Koln and Frankfurt (I think). Our first setting-up camp was in pouring rain next to an autobahn service station - at least we had somewhere in the dry to eat. There's a picture of us picnicking next day - Patrick's note says "near Wurzburg". From right to left: Michael,Braidwood, me (those sideburns!), Chris Smale, Pete Sheppard, Philip. We reached Munich mid afternoon. Did we adults really neck three litres of Lowenbrau each? Yes we did; I clearly remember Philip (normally so straight-laced) saying "This is rather nice, Andrew, I think we'll have another". I then took the wheel and we headed on to Salzburg. We camped south of the city, just off the road (campsites were not something we bothered with), and spent the evening in town with the sound of music (it was the Salzburg Festival).

Once across, we drove via Ostend, and spent the night somewhere between Koln and Frankfurt (I think). Our first setting-up camp was in pouring rain next to an autobahn service station - at least we had somewhere in the dry to eat. There's a picture of us picnicking next day - Patrick's note says "near Wurzburg". From right to left: Michael,Braidwood, me (those sideburns!), Chris Smale, Pete Sheppard, Philip. We reached Munich mid afternoon. Did we adults really neck three litres of Lowenbrau each? Yes we did; I clearly remember Philip (normally so straight-laced) saying "This is rather nice, Andrew, I think we'll have another". I then took the wheel and we headed on to Salzburg. We camped south of the city, just off the road (campsites were not something we bothered with), and spent the evening in town with the sound of music (it was the Salzburg Festival).

Yugoslavia

We woke early - it was a glorious morning, and we were soon climbing the Alps. Our route took us along the Drava - a swim seemed like a good idea. We drove to the water's edge, stripped off and were immediately in difficulties. There was a mighty current and we nearly lost Pete at this early stage. Health and safety was an as yet unheard of luxury - and this experience didn't deter us from future swimming whenever the opportunity arose. Pete stayed on shore, though.

We woke early - it was a glorious morning, and we were soon climbing the Alps. Our route took us along the Drava - a swim seemed like a good idea. We drove to the water's edge, stripped off and were immediately in difficulties. There was a mighty current and we nearly lost Pete at this early stage. Health and safety was an as yet unheard of luxury - and this experience didn't deter us from future swimming whenever the opportunity arose. Pete stayed on shore, though.

That evening we were in a wooded park outside Zagreb (or it may have been Ljubljana). They were roasting lamb on the spit - for anyone who wanted to buy a portion. We enjoyed (though we we didn't then know it) our finest meal of the entire trip. In the morning we hit the autoput, the lethal 2-lane "motorway" linking Zagreb with Belgrade - a flat straight ribbon across the featureless Pannonian plain. There wasn't much traffic - to judge from the frequent piles of tangled metal at the roadside, few vehicles actually managed to complete the journey.

But our early start meant we were in Belgrade by lunchtime. Yugoslavia was still a single country under Tito - but Belgrade was lively, though drab, with plenty in the shops, and well-dressed people in the streets. And - to Patrick's delight - trams: none in Britain since the closure of the Glasgow network in 1962. We remembered for the first time that we were tourists, and climbed up to the Kalemegdan fortress to admire the view over the confluence of the Sava and the Danube. We drove on, not stopping until well after nightfall, when we turned off the main road (somewhere in Macedonia, I guess) and put up the tents in a field. We were woken at dawn (about 4 am?). It was somebody's cornfield, and they'd come with their carts to finish the harvest. I realised why, when as a tourist you're looking for breakfast around 10 am, the cafes are already full of apparent idlers. It's simply that, starting work at 4, they've done a full day's work by elevenses time! And the rest of the day is theirs for gentle sipping of coffee, or whatever, and putting the world to rights. Is this why democracy arose in the Mediterranean world?

But our early start meant we were in Belgrade by lunchtime. Yugoslavia was still a single country under Tito - but Belgrade was lively, though drab, with plenty in the shops, and well-dressed people in the streets. And - to Patrick's delight - trams: none in Britain since the closure of the Glasgow network in 1962. We remembered for the first time that we were tourists, and climbed up to the Kalemegdan fortress to admire the view over the confluence of the Sava and the Danube. We drove on, not stopping until well after nightfall, when we turned off the main road (somewhere in Macedonia, I guess) and put up the tents in a field. We were woken at dawn (about 4 am?). It was somebody's cornfield, and they'd come with their carts to finish the harvest. I realised why, when as a tourist you're looking for breakfast around 10 am, the cafes are already full of apparent idlers. It's simply that, starting work at 4, they've done a full day's work by elevenses time! And the rest of the day is theirs for gentle sipping of coffee, or whatever, and putting the world to rights. Is this why democracy arose in the Mediterranean world?

We exchanged pleasantries with our hosts (Richard Janko had mastered a few words of Serbo- Croat - I only knew how to say "I do not speak Serbo-Croat", though in a great accent); they were very tolerant of these eccentric visitors from another world.

We exchanged pleasantries with our hosts (Richard Janko had mastered a few words of Serbo- Croat - I only knew how to say "I do not speak Serbo-Croat", though in a great accent); they were very tolerant of these eccentric visitors from another world.

Arriving in Greece was a curious experience. After leaving Tito's communist – but comparatively liberal - Yugoslavia, it felt as if we were entering a fascist, militarist state. No hippies or even men with long hair were allowed to cross the frontier (I was worried about my sideburns): so much for the ϰάρη κομοῶντες ᾿Αχαῖοι!

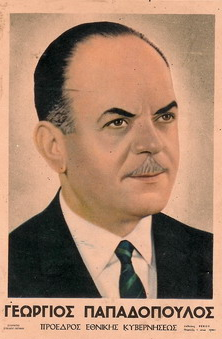

Soldiers were everywhere, and the sinister portrait of Colonel Georgios Papadopoulos glowered down at one from every cafe, shop or taverna – and from the banners across streets in even the remotest village reminding us all of that most vital date in Greek history – 21 April 1967. We truly felt we'd been fast-forwarded to 1984: Big Brother was not yet a harmless disembodied voice on a TV show. I certainly remember the relief when we finally crossed back into Yugoslavia at the end of our tour in Greece – at last we were back in a free country!

Greece

Greece

The first night in Greece was in a noisy and crowded youth hostel in Thessalonike (the first time we'd had to sleep indoors since leaving Bedford). We ate on the pavement outside – stuffed peppers well-seasoned with diesel fumes, but washed down with our first retsina, to restore the sense of adventure. Next day, after a morning doing the sights, Patrick introduced us to the excellent Mediterranean tradition of the post-prandial snooze: a town square, a bench and glorious oblivion (fuelled by the retsina) was ours.

Meteora

Next day we headed south, paying our respects to Olympus as we passed. That night was one of the most memorable ever - not just of the trip, but of my whole life (with all I've experienced in the 40 years since). Patrick on earlier tours (he used to take small parties of students round Greece in a minibus for the Aegina Club) had made friends with the lone Orthodox monk in Aghia Triadha (Holy Trinity) - the most vertiginous and smallest of the monasteries on pinnacles of rock known as Meteora (τὰ μετέωρα, "the things in mid-air"). He was a cheerful man in his early forties or so, who had not left his eyrie since completing his vows at 18. His only companion was a teenaged boy, who had not yet decided whether the life of a solitary monk was for him - and could still come and go. As we were later shown, he had a fig-tree, vines, and a tiny vegetable patch - but relied mainly on gifts of food from the village below, which he hauled up in a basket: this was once the only way of access for visitors. A recent innovation was a cable stretched across from a point on the road, along which it was possible to travel in a motorised bucket. Only Patrick was brave enough to trust it - the rest of us preferred to scramble down to the bottom of the valley, and then up again on a steep stairway carved out of the rock.

Once up, we had a simple candle-lit supper, followed by a tour of his domain, including the tiny chapel with its frescos and icons. Then a perfunctory wash (the only water was rainwater) and an early night in the dormitory - intended once presumably for a community of monks.

During the night - what an absurdly dramatic cliché - there was the mother and father of all thunderstorms, as if Zeus was trying to test the resolve of this upstart religion.