Socrates

The trial and death of Socrates

Background

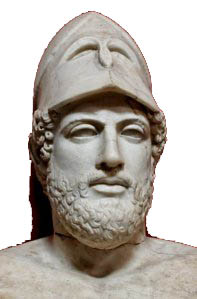

The year is 399 BC. Pericles, the inspiration of Athenian power and prosperity, had died 30 years before, after having led his fellow-citizens into a war with Sparta, which he thought they could not lose. The war was to last until 404 BC, with terrible suffering on both sides. When Athens finally surrendered to the Spartan Lysander, it was almost a relief. Even when the democracy was restored a few years later, people were no longer excited and enthusiastic, but cynical and bitter. They wanted someone to blame for their decline. And there was an obvious scape-goat – a man who was now 70, but had spent his whole life in Athens ...

The Agora: Socrates seldom strayed outside the area shown on this map.

The pnyx for monthly assemblies of the people, the theatre and the acropolis

for festivals, the agora for daily social life - and the lawcourts for his trial.

And, regularly, the shop of Simon the shoemaker.

Simon's shop

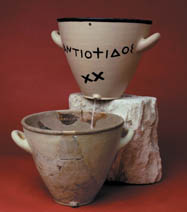

Just outside the agora, Athens' "central business district", was small house, used as a cobbler's shop, and owned by a man called Simon. Or at least that's the deduction from the number of eyelets and hobnails found there - and a black-glazed cup with Σ Ι Μ Ω Ν Ο Σ (Simon's) inscribed on it.  And we know from Plutarch that Socrates used to meet young men in the house of Simon the shoemaker just outside the agora (no entry to the agora was allowed for under 18s) - and that this Simon wrote an account of the trial and death of Socrates.

And we know from Plutarch that Socrates used to meet young men in the house of Simon the shoemaker just outside the agora (no entry to the agora was allowed for under 18s) - and that this Simon wrote an account of the trial and death of Socrates.

What follows is Simon's story (as I imagined it! With help from Plato and Xenophon, of course.)

The agora

As far back as I can remember I was always being told, by my mother, my father, my grandfather, my big sister "never go past the white stone". And so of course I got obsessed by this stone, which was right next to our house. It was marble, rectangular, about two feet high – probably about the same height as I was when I first got told off. It had some funny markings on it – later, when I learned to read, I found out, as you'll have guessed, that it was writing. It said (in Greek of course!) HOROS EIMI TES AGORAS. "I am the boundary of the agora." As I got to explore our neighbourhood, I found lots more stones, just like ours: but always if I tried to go past one, there would be men shouting at me: "You, boy! You are too young! Get back!" Well, as you may imagine this made me very curious indeed to find out what was so special about this "agora". What was it that went on there that was so unsuitable for a child even to see?

The banned area was roughly square, about 200 metres along each side. Within this square everything, as one of the poets said, was available - 'figs, prosecutors, bunches of grapes, turnips, pears, apples, roses, medlars, haggis, honeycombs, chickpeas, lawsuits, myrtle berries, computers, hyacinths, lambs, water-clocks, laws ...'

Everything an Athenian could ever need was on sale there – except shoes, of course, which they'd have to buy from us!

I also found out about other things that went on there, apart from shopping and gossip (which all Athenians love) and political argument (which we love even more). In particular the agora seemed to be the home of the law-courts, which Athenians love even more than politics – especially since anyone over 30 could earn 3 obols a day just for being a dikast - on a jury, that means.

I should explain a bit more. My family have always owned the leather workshop just outside the agora where I grew up, and where – I'm middle-aged now – I still work, and teach my skills to my son. My name is Simon, which was also my father's name – and the name I've given my son – just to avoid confusion. The shop has always been "Simon's", and none of us would want that to change! As I've explained, the agora was out of bounds to anyone under 18 (as well as to convicted criminals – we always thought that was a bit harsh, lumping us in with crooks!). So the lads used to hang out just outside the entrances, especially the one right by our shop. For some reason, we became quite a social centre: anyone who wanted to find out what young people were thinking would come into Simon's and chat. When someone like Pericles used to drop in, we could give him a proper grilling. Although we couldn't vote like grown-ups, we could certainly get our feelings across to the top man.

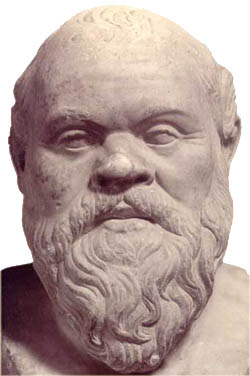

Socrates

But mostly it was Socrates. He was always interested in getting discussions going with the young folk – although he used to tackle the adults in the agora as well. But he was always around somewhere, summer or winter, wearing the same old smelly robe – he didn't seem to feel the cold ever, or suffer from the heat. And, although he was there all the time, he was a rotten customer, as he never wore shoes! He was one of the real characters of Athens – everyone knew the tubby man with the bald head, snub nose, staring eyes – and we loved it when took on one of our more pompous citizens. He had a method: he'd start asking them about their job – especially if they were involved in politics, or something where they reckoned they were pretty important. Sometimes it seemed as if they didn't have the faintest idea what they were talking about! We used to laugh so much to see him in action! Mind you his victims were never that grateful. You'd have thought they would have been, when instead of thinking they knew something, Socrates proved that they didn't. He always taught us that you can't learn anything until you admit that you know nothing.

Another weird thing about Socrates was his daimonion (his "mini-god"). He always said he had this "daimonion" which always stopped him when he was about to do something wrong or stupid. Once he and some friends were walking through "the sculptors" in the agora on their way to the law-courts (the areas all get their names from whatever business goes on there). Suddenly he left them and went off through "the box-makers" instead. A great herd of pigs then came crashing through the sculptors on their way from the market. Socrates friends emerged dirty and stinking – with a new respect for his "mini-god"!

Mention of the law-courts brings me back. For most of his life, Socrates was to be found in our shop, or around the agora talking to people, asking them why they believed what they did. He believed that it's best for people to live without false ideas about themselves. And Socrates set an example – he dressed as simply as possible, ate simply – though he wasn't one to turn down an invitation to a party (what we call a symposium). A symposium could often be a bit of a drunken rowdy occasion, though if Socrates was there, there'd usually be some intellectual discussion with the wine, rather than flute girls and kottabos. But he was already pushing 70 when it all changed – and he found himself on trial in the agora, in one of those law-courts.

Democracy

You probably know that Athens is called a 'democracy'. That means that everyone gets a chance to do his bit. Even Socrates had his turn as president ( prostates tou demou: you only ever got one day in your life) – the people then were in an angry mood and wanted the death penalty for some generals who'd won a victory at sea, but failed to rescue the dead bodies. Socrates used his power as president, and refused to allow a vote. But of course next day it was someone else, and the people got their way. So that's what democracy means – the people always get what the majority of them want. But of course they are influenced by the real leaders – the men, usually rich men, who become generals, and others who can persuade them because they are good speakers.

This could be fine when the leader was a man like Pericles – who was re-elected general by his tribe year after year. Pericles led us to victory after victory over our enemies, and helped us bring back so much loot that we could afford to build the Parthenon, and many other magnificent buildings. But since he died, nearly 30 years ago now, we've had some shockers. There was one, Alcibiades was his name, who actually persuaded the people to vote to suspend democracy! For a couple of years after that we had an oligarchy – only 400 were allowed to vote and be part of the government. We got rid of them, but we were still at war – fighting the Spartans and their allies as we'd done most of my lifetime – since the days of Pericles, anyway. But only a few years after that, we finally lost: the Spartans marched in and occupied us, and put in a government of their friends – yes, they did have friends in Athens, traitors! They chose only 30 – we hated them so much we called them the 30 tyrants.

Trouble was that Alcibiades as a young man had been very close to Socrates – he was one of those hanging out in our shop, you may be sure. I remember how handsome he was as a young man – my sister really fancied him, and he used his good looks to get round anyone, including Socrates! Other 'old boys' included several of the 30 tyrants, one being the worst of them, Critias. Socrates – though you could not have found a more patriotic Athenian (he was a war hero, and never left Athens except to do his military service), never really believed in democracy as the best way to govern us – he was forever showing how our would-be leaders did not know what justice, truth, courage, honour, freedom and so on were – although they talked about them incessantly!

So when we kicked out the 30 and got our democracy back, they looked around for someone to blame. For the 30, for losing the war, for the humiliation. And the new leaders thought at once of Socrates – he'd been a friend of Alcibiades, he was known for talking down the democracy. There would be a trial – a spectacular trial. But what to charge him with? They could hardly accuse him of speaking his mind, in a democracy which prided itself on its freedom of speech (you should have heard the things that Aristophanes got away with saying on stage in the theatre in his attacks on our revered leaders!). So they remembered two things that he'd never made a secret of – they accused him of "introducing new gods" (as if his personal "mini-god" was anything other than a kind of joke), and of "corrupting the youth". Certainly he'd talked to Alcibiades and others, often in our shop, but can a teacher really be held responsible for the way his pupils turn out?

There are trials every day in the agora – some say we Athenians are addicted to the law-courts. Apart from the pay – one of Pericles's most popular measures - there are actual benefits of being able to settle a quarrel without any need for fighting or violence. They say that in the old, old days, before the law-courts were invented, whole families actually used have feuds with each other – long after whoever started the quarrel was forgotten, their descendants would be murdering each other in a non-stop vendetta. When we see our old stories dramatised in the theatre, we can all be very relieved that nowadays we have more civilised ways of doing things. Not that vindictiveness has gone entirely: Socrates's trial was a case in point.

There's no one in Athens whose job it is to bring people to court – if it's a dispute between neighbours, over a boundary or some such, then one neighbour takes the other to court. They each have a chance to put their side – equal time, thanks to a brilliant modern invention, the water clock – then the dikasts vote. Whoever gets the most votes wins. There is no appeal – their decision is final. So our dikasts, are really judge and jury. Then the winner and the loser each have a chance to suggest what damages should be paid – and the judges vote again to decide between the two penalties – usually a bigger or smaller fine.

But if it's a crime against the state, anyone can prosecute – and keep a percentage of any fine if he wins! This has led to a lot of vindictive law-suits, as you could well imagine. There's always a large number of judges, selected by computer – to make it too expensive to bribe everyone, and there's always an uneven number -101, 201 and so on. If one of them gets ill or dies during the trial – not that uncommon where they are all old men – an equal vote always means the accused gets off (because of an old tradition that our goddess Athena, who organised the first ever trial when Orestes came to Athens after murdering his mother, voted for mercy after the men had found him guilty by one vote. She made the votes even, and ever since we think of Athena voting with us to give the accused the benefit of the doubt).

The trial begins

Once all the 501 of us were in place, the trial began. Socrates' accusers spoke first, arguing in favour of the two serious charges – not believing in the city's gods and introducing new gods; corrupting the young men. They had a good deal to say about Socrates' being an atheist, and his association with Critias (one of the 30 tyrants, who was definitely an atheist!) and Alcibiades. I thought they were very convincing, and when Socrates started his speech in defence, he pretended he thought they were pretty good, too. But I, and most of my fellow jurymen knew that this was the way Socrates always talked, not always saying what he meant – there was even a special word for it: irony. This is when you pretend you don't know something. There was plenty of irony in Socrates's speech.

We aren't allowed to write anything down when we're in the jury, so my recollection of what he actually said may be a bit impressionistic. But afterwards, back in the shop, there was much discussion among Socrates's friends, and some of it I got from them. There was a young guy, Aristocles, who we called Plato – a nickname which means 'broad-shouldered' in Greek, who said he was going to write it all out in full and publish it. I don't know whether he ever did, but he was a great help when we were trying to reconstruct Socrates's words afterwards. Anyway, I made my own notes, which I'd always done after being there for one of Socrates's discussions.

So these are some of the highlights which we remembered. He claimed that he hadn't prepared his speech - I learned later that his daimonion had told him not to. He supposed this was because at the age of 70, it was time for him to die, before the various afflictions of old age kicked in. Throughout his life he had never been one to be afraid of death.

Socrates's Defence

The words in heavy type are extracts based on two surviving accounts of Socrates's speech at his trial, by his friends and pupils Plato and Xenophon. Simon's commentary continues:

The 'old accusers'

First of all, he had quite a bit to say about those he called his "old accusers" - for the last 30 years or more, comedians had mocked him – he was an easy target after all, and even his friends used to find it funny. But now that he was on trial for his life, he believed that a lot of people – including many of our 501 – were judging him as if he really were this comic character.

Socrates: "They say 'Socrates does wrong in probing into things under the ground and in the sky, and making the weaker argument seem stronger, and teaching others to do these things.'"

That's how Socrates was shown in Aristophanes' play Clouds: he appeared bent double, staring at the ground, studying "things under the earth". When another character asked why his bottom was sticking up in the air he replied "because it's taking a course in astronomy". Socrates said in court – which anyone who knew him could back up – that he had no interest in geology or astronomy. He was also very keen to prove that he wasn't a teacher – he had no pupils and he never charged anyone, unlike the freelance teachers that practised in Athens – the sophists, who accepted vast sums of money for making people "better" at something. But Socrates did agree that, for some reason, people believed he was wise. This is roughly how he tried to explain it:

"I guess you knew Chaerephon. He was a friend of mine since we were boys, and a very devoted one. Once he was visiting Delphi, and dared ask the god Apollo this question – please don't shout me down – 'Is there anyone wiser than Socrates?' The reply came: 'No one!' Why am I telling you this? I want to show how a misunderstanding came about. When Chaerephon told me, I said 'What can the god mean? It's a puzzle. There's not one subject, big or small, in which I am the wisest. But a god can't be lying, surely?'

There was quite an uproar from the jury, and the spectators, when Socrates said the bit about Chaerephon's question to the god. There were interruptions, too, during the next part of his speech:

"After pondering about the meaning of this for a long time, I eventually set out to try and find an answer. I questioned a man with a name for being wise, sure that I could prove the god wrong, if I showed that this man was wiser than me. As I interviewed the man – he's a politician, but I'm not saying who – it seemed to me that he appeared wise, especially to himself, but in fact wasn't. When I tried to convince him that he only thought he was wise, but actually wasn't, he became quite cross with me.

"And so I went away, thinking to myself: 'I am wiser than this man. Chances are that neither of us knows anything worthwhile, but he believes he knows something which he doesn't. I am just as ignorant, but I don't believe I know anything. So perhaps I am wiser than him in this, because I don't believe I know what I don't. I know that I know nothing.'

"Then I went to another man, with an even greater name for being wise. I interviewed him, and came to the same conclusion, and put him, too, in a bad temper. I interviewed more and more people, making myself more and more unpopular. But I felt I must keep testing what the god had said. And, by the dog, I found the people with the greatest name for wisdom actually had the least – while the more ordinary the person, the wiser he turned out to be."

Socrates then described how he interviewed a lots more people from all walks of life, and always came to the same conclusion – people everywhere think they are wise, but aren't. And the more pompous they are about it, the more they resent it being pointed out! As an ordinary cobbler, I'd loved watching him cut the politicians and posers down to size.

"As a result of all my questioning, I have incurred a great deal of dislike and hostility. And I think this is where my name for wisdom comes from: if I show someone up as ignorant, people assume that means I am wiser than them. But perhaps only god is truly wise: what the god meant was that human wisdom is pretty worthless. He just used me as an example: 'the wisest man is someone, like Socrates, who knows he is not wise.' And so I carry on doing the god's work, questioning people and showing them that they know nothing."

So Socrates deals with his "old accusers", and tries to explain his reputation for being some clever teacher. Then he moves on, to deal with the current accusations – that he was a bad influence on young men, and believed in gods of his own invention. As for the gods, he claimed that he joined in with all the sacrifices that he should – but what they hadn't liked was his "mini-god", as if the city gods weren't good enough for him, or that he had some special god they didn't. But he said it was no different from folks who listened to bird-calls and oracles – just another way the gods warn people. A poet called Meletus was one of his accusers. Socrates actually cross-examined him in court, something like this, as far as I remember:

Corrupting the youth

Socrates: We all know the sort of bad things young people get into – not respecting the gods, wasting money, drunkenness, avoiding exercise. Do you know anyone who's been led astray like this because of me?

Meletus: No, but I know plenty who've learned to listen to you and not their parents.

Socrates: But do people listen to doctors, rather than their parents, if there's a health problem? Do the Athenians elect experienced military men as generals rather than their fathers? In the pnyx, do we all listen to the best speakers, rather than our relatives?

Meletus: That's very true, we always have done.

Socrates: So isn't it odd that we respect and honour people who are good at some things, while I am put on trial for my life by you for – as some people think – being good at educating the young, the most important thing in life?

Meletus did not seem at all happy about this, and when Socrates continued he became even more upset! Socrates went on to answer a point in the accusers' speech, that he was a fool to pursue an activity where he risked death. Did he regret his choice?

"No. A man shouldn't decide what to do because he's worried about his chances of dying. His only worry should be whether he is doing what's right or what's wrong. Imagine if Achilles had thought like that! He knew that death was certain if he killed Hector. But it would have been wrong not to avenge his friend Patroclus, who Hector had killed."

Socrates had never been afraid of death, either in the army, or in the city, when he'd refused an order from the 30 to go and arrest an enemy of theirs. So Socrates showed not the slightest regret for the way he'd spent his life. This is how he ended:

"Suppose my accusers were to say 'Socrates, we'll let you off, if you promise to change your life-style, and give up being a philosopher and asking questions. But if we catch you at it again, it's the death penalty for certain.' My reply would be: 'Thanks very much, gents, but I'd rather obey the god than obey you. As long as I have breath, I shall never give up my search for wisdom. I shall bother and badger anyone of you I meet, saying: 'You are citizens of Athens, a city famous for its power and wisdom. Aren't you embarrassed to spend your life in pursuit of money, ignoring the pursuit of honour, wisdom and truth?"

There was much more that Socrates said, but in the end he seemed to be somehow asking to be found guilty. He refused to apologise, or even sound sorry for anything he'd done in his life. He even refused – the usual thing people did – to try and make the jury feel sorry for him. I could tell from the way my fellow-jurors were reacting, that they were not liking it. Perhaps the final straw was this:

"If you kill me, you won't easily find anyone else like me."

At this point people around me started laughing

"No, seriously, this is not meant to be funny. Imagine a large lumbering cart-horse. It needs a horse-fly to sting it into action. In the same way this city needs me – and I was sent on purpose by the god. That's why I spend all day, settling on you at random, stinging you, badgering you, pointing out your faults ..."

Soon afterwards it was time for us to vote... Continue to the verdict and sentence.